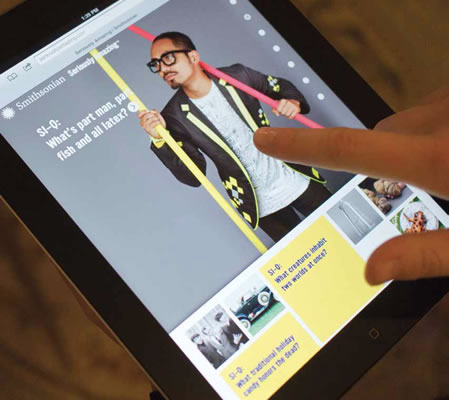

Beyond Museum Walls

In the past few years, museums and other arts institutions have been able to extend their reach far beyond their brick-and-mortar walls by utilizing new technologies and trading in their “temple on the hill” reputations for interactive, user-friendly identities. Few institutions have handled these changes as adeptly as the Smithsonian Institution. With 19 museums in Washington, DC, and New York, the Smithsonian has amplified its campuses with dozens of apps, blogs, mobile sites, Twitter feeds, Pinterest boards, and Facebook pages. Overseeing much of it is Nancy Proctor, Smithsonian’s head of mobile strategy and initiatives. In addition to her current work at the Smithsonian, she is co-chair of the Museums and the Web annual conference, and manages MuseumMobile.Info, a site designed to facilitate and inform conversation about museums and technology. Recently, we spoke with Proctor about her work at the Smithsonian, and the effects and future of museums in the digital age.

NEA: The Smithsonian is obviously unique in that there are 19 museums. How has mobile strategy been used to solidify the museum’s collective identity?

NANCY PROCTOR: I don’t know that it has. But it certainly is very sympathetic with the new brand strategy that the Smithsonian has adopted. The new brand strategy really espouses some fundamental social media principles about it being as important to listen as to speak. [It’s] trying not to occupy the position of “the sage on the stage,” as they call it, but to be more in conversation with our audiences and responsive to them and focuses on engagement in new ways.

NEA: In terms of reversing “the sage on the stage” mentality, do you think crowdsourced curation poses any risk in removing a layer of expertise that the Smithsonian is known for?

PROCTOR: In short, no. This is the same conversation that’s going on all around the world. Putting an expert’s knowledge in conversation with a larger audience is frankly how experts have always [enhanced] their knowledge: through networks and conversations with a wide range of people of varying expertise. Nobody should feel threatened by that. If anything, with the increase of information on the Internet and in the network world in general, I think the value of experts in helping us navigate through the noise is increasing the more that they are participating in that wider conversation. Beyond that, experts make mistakes all the time and the “lay” audience or nonexperts (i.e., people who don’t work for the Smithsonian) have a hell of a lot of expertise that we would like to tap into.

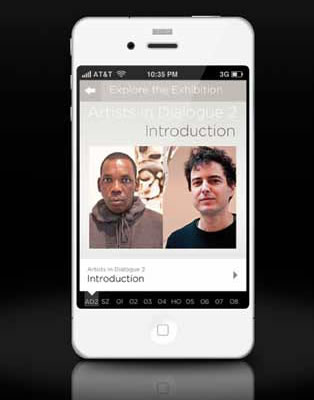

Some Arty Apps from the Smithsonian

Leafsnap: Using visual recognition software, this app allows users to identify tree species simply by taking a picture of its leaves.

Access American Stories: This app accesses audio descriptions of museum objects as recorded by museum visitors. The recordings allow those with visual impairments to “see” an object with their ears.

goSmithsonian Trek: Instead of a traditional museum tour, go on a scavenger hunt—complete with clues and challenges—through the most popular exhibits at nine Smithsonian museums.

Stories from Main Street: This app collects users’ stories of small town and rural life. Record your own, or listen to those left by others.

Romare Bearden Black Odyssey Remixes: This app allows users to create their own digital collages using personal photos, words, and cut-outs, as well as snippets from Bearden’s works.

NEA: Apps like LeafSnap [see sidebar for description] go beyond what’s on exhibit while still promoting Smithsonian’s main mission. In this regard, how is technology changing the traditional museum experience?

PROCTOR: Museums have to think far beyond their physical buildings and the people who come to them now. Obviously, an increasing majority of our audiences are carrying around some sort of a mobile device. Those devices are network-connected, which means that they enable us to engage people not just in dialogues, but to connect them to larger, multimodal conversations. So certainly for the Smithsonian, with its mission of increasing and diffusing knowledge for all, it would be very shortsighted not to avail ourselves of this platform, which is nearly ubiquitous now and so very powerful in creating the kinds of connections and conversations that would really help us further our mission.

NEA: In your opinion, what are the benefits of making museums increasingly social experiences?

PROCTOR: For the Smithsonian, that’s a no-brainer. We’re the people’s museums, so if we want people to want to come here, or want to use our collections online, or simply be part of conversations that the Smithsonian has started or is part of, we have to make those experiences engaging. And for a lot of people, the social nature is what makes something engaging. Now that’s not true of everyone. Some people certainly seek out museum experiences precisely because they want to get away from everyone and be contemplative, and that’s fine, too. We need to support that as well. But I think, typically, museums have done a much better job of supporting scholars and subject specialists than they have more general audiences who might be interested in a more social experience. When you think about working to find ways that an interaction with the museum—as a physical visitor or through some sort of online participation—can transcend generations, that [interaction] can involve families or classrooms. That’s very powerful indeed in terms of building an audience and a brand loyalty that will be sustainable for the long-term.

NEA: Speaking of sustainability, technology is obviously changing at an incredibly rapid rate. What does the Smithsonian do to try and ensure that the technologies it is developing are sustainable?

PROCTOR: We need to do a much better job of thinking about how to work with content and content providers who are already out there, be they Wikipedia or crowdsourced content like what you might find on Flickr or YouTube—making sure that we’re not re-inventing the wheel.

But one thing that is starting to happen more and more is that when museums invest in creating content, they’re starting to think a little bit more about how we can use it in multiple places. That’s really a function of the huge cost of content generation. It should be the most expensive thing that we do, and therefore we should be thinking about how do we use it in as many different ways as possible and ensure that we can continue using it over time. In the past, a shortsighted approach has put investment in the technology over investment in the content, and the technology, as you say, is so rapidly obsolete.

NEA: What kind of experience do you think the Smithsonian is offering people who for either geographic or economic reasons aren’t able to visit Washington?

PROCTOR: The thing about the Smithsonian is it’s so big and there is so much going on, that I guarantee you I only know about a small fraction of it. Every day I come across some amazing thing that we’re doing that I didn’t know about. So there are pockets of real excellence in terms of using technology for outreach. I do think that that’s a critically important tool. That’s why I’m working with mobile: not just because I want to reach the people who come to our physical buildings, but because I want to reach everyone everywhere, whenever they might want to connect with us.

The director of the [Smithsonian] Freer Sackler has expressed this very well, I think. Julian Raby said that the first generation of museums on the web was about putting information out there, putting collections online, telling people what we’ve got. That was important because we have a lot of stuff that’s simply not visible in the buildings, and making that content and data accessible online is a really important mission. But now that a lot of that stuff is out there—we know how to do that now. We need to start thinking about how do we use those network platforms, those digital platforms, to create experiences, not replicate the experience of a physical museum visit. I think you’re fighting a losing battle if you’re trying to make up for geographic distance and physical separation. But [you can] provide complementary and alternative experiences so that even people who cannot afford a hotel room to come to Washington, DC, or to New York, can still have a profound and moving and transformative experience of the Smithsonian. That’s our challenge now, to think about how to use technology to enable people to engage not just on an intellectual, informational level, but to engage emotionally as well.

We also need to be thinking beyond even web and mobile to how technology in physical installations can allow access to content that wasn’t previously available. Again, Freer Sackler recently hosted the installation called Pure Landby the ALiVE Lab out of City University of Hong Kong. That’s a work created by the artist Jeffrey Shaw with Dr. Sarah Kenderdine and their team. They scanned in extremely high-resolution images of one of the caves in Dunhuang, China, which are almost impossible for anybody to visit. A small number of the caves are open for short periods of time, but you’re in darkness to preserve the paint of the caves. You can explore with a flashlight. But with these high-resolution scans installed in a virtual reality cave, you can virtually visit those caves and zoom in and see details that, frankly, would be impossible or practically impossible to see in person. We had a similar experience when we joined the Google Art Project and they did Google pixel scans of selected artworks. The way that you can zoom in and see the brush strokes and the cracks in the paint—again, that’s a level of access that’s hard even for the curators and conservators in charge of the objects to get. Those are obviously really important uses of technology, but, again, they’re just tools. They’re just supports for getting closer to the content. They’re not the end in and of themselves.

NEA: What do you see as the long-term effects of technology on the museum world?

PROCTOR: I think it’s easy to get distracted by the gadget side of technology and think that, “Oh, if we have an app then the museum’s totally different.” For better or for worse, quite often new technologies come into old institutions and, frankly, not much changes. The museum is still structured in the same way. There might be different people in power, but the structure of power remains the same in terms of who calls the shots and what a museum is and what it does and how it communicates with the public. So what I would hope is that we’re inspired by technology to interrogate the way that we’ve always done things. Sometimes we will find that new platforms and new ways of working with technology will give us ideas about how to fundamentally restructure our institutions and change the way we work. Other times it might point out that actually certain practices have been around for a long time. The Smithsonian has been crowdsourcing since the mid-19th century when it opened its doors. It wasn’t using apps; it was using the telegraph machine. But it was the same fundamental concept of we’re the people’s museum and we’re built in partnership with the people. The technology gives us more powerful tools for achieving that mission…. It’s so easy to fall into these knee-jerk polarizations of “I’m pro-technology,” “I’m anti-technology.” The really useful questions lie much deeper than that, I think: What do we want to change and how do we want to change it?