That Space Between

Washington, DC-based Ryan Holladay lives a double life. He’s not only one-half of the music duo Bluebrain, which he founded with his brother Hays, but he’s also the curator of new media at Artisphere, a contemporary arts space in northern Virginia. A newly minted TED fellow, Holladay’s arts practice revolves around place, both as a setting for and also as a character in the musical compositions he creates. Here is an excerpt from our interview with Holladay, which took place as we walked through several of Artisphere’s galleries. We finally seated ourselves on an array of lightboxes while taking in a changing panoply of tweets projected as part of the interactive installation W3FI.

NEA: How did your arts practice evolve from the kind of electronic music that Bluebrain originally produced to site-specific work like The National Mall album app?

RYAN HOLLADAY: I think Hays and I had always talked about these kinds of concepts and ideas for installations. But it felt like, for whatever reason, we needed to make our way as musicians first. At one point, I think it sort of hit us that there was no reason to wait to experiment, and the idea of music and sound interacting and responding to physical space was always fascinating. One experience that sticks out was visiting Central Park and seeing Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s The Gates, a massive installation of hundreds of brightly colored metal beams draped with fabric—I had never seen anything like that before. I was in college at the time, and it was just a real eye-opener for me in terms of how art can transform how we think about a physical terrain and speak to the landscape. It really planted a seed that would later manifest itself in the form of the location-aware albums we’ve created. They are obviously a completely different kind of project, and I certainly don’t put what we’re doing on that level at all. But I think the idea of location-based music stems from that experience in a lot of ways, of how an artist can use a landscape as canvas. In the case of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, it’s a very physical manifestation. In our case, it’s a virtual layer that’s placed atop a physical place using a smartphone’s built-in GPS functionality. But both are responding to space, and that’s been central to much of the work we’re doing.

NEA: When I was going through your website I was very struck actually by the fact that you use the phrase 'location-aware' as opposed to 'site-specific.’ Can you talk about that language?

HOLLADAY: It's kind of a clumsy name, and we were never sure what the best phrasing was for it, but ‘location-aware’ became the buzz phrase for apps that use any sort of augmented reality. ‘Site-specific’ doesn’t fully convey what we’re doing. The Gates is site-specific in that it was created for a specific place, but the work isn’t continuously recalibrating based on your placement within the park. In our case, the app figures out where you are and then changes the music based on your actual location. So that was the distinction we were making—that the app is responding to your movement and following you around.

NEA: So what was that leap where you went from making records and performing live to “Hey, let's go make something that responds to a space”?

HOLLADAY: A lot of the works we had done up until that point had been music linked to a physical space but using much less sophisticated tools. One of the first projects we did in this area was creating a music accompaniment for the Ocean Hall in the Smithsonian Museum of Natural History. But the only way we knew how to accomplish this was to create a score based on the length of time it takes for the average visitor to make their way through the exhibition. It was a static linear piece intended to be used in a specific place along a designated path, not unlike the work of Janet Cardiff. It was not “smart” in the sense that it responded to movement or allowed any sort of autonomy on the part of the listener. But with the introduction of apps came the ability to integrate user feedback just by their movement from one place on a map to another. The prospect of creating an album as an app opened up the possibilities.

Meanwhile, we were seeing this explosion in innovation happening with mobile technology, but it seemed artists—and certainly musicians—were really not scratching the surface with it. Some were using apps to make games related to music or even tools to make music with, but it didn't seem like anybody was using these new parameters to compose music in a completely different way. That’s where we became excited, [at] the idea of using these new things to create music in a totally new way, and also as a listener to experience it in a very new way as well.

NEA: I am curious about your National Mall project—how do you enter into that project in terms of inspiration or figuring out how to move through the space?

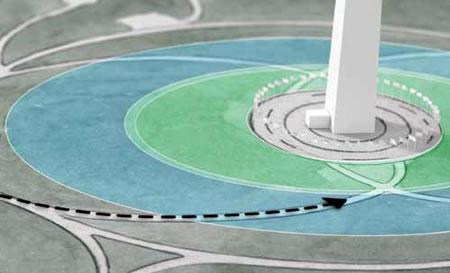

HOLLADAY: The National Mall was the perfect first site to experiment with this concept because of the physical arrangement of the park itself. While there are unique landscape ideas in various sections throughout the park, the overall framework of the Mall is symmetry. That lent itself to coming up with a methodology to musically approach a physical terrain for the first time. It felt a bit like we were playing with bumper lanes. There are parts where you can wander off, which we enjoyed playing with, but there is really only one way to walk from the Capitol to the Lincoln Memorial.

One space we used was the Washington Monument. We clearly saw that square, the grounds leading up to it, as one piece, as one motif. So as you cross the street going into that square, you hear, I think it's piano and a single cello, and as you climb the hill, more and more elements come in. As you reach the giant obelisk, you hear more strings and then a choir, and then when you are finally touching the monument, when you are up against it, you're hearing out of control heavy metal blast-speed drums. But then if you go the other way, it all happens in reverse. The idea is that it’s complementary to what you are actually experiencing physically as you are getting closer to this thing that is so massive. So that really worked well because it gave the whole thing an anchor.

NEA: Hearing you talk about it, you almost seem to be suggesting a musical narrative for how you are moving in space.

HOLLADAY: It's interesting, because we decided early on we weren't going to have any words throughout the whole thing because we didn't want to color someone's experience to that extent…. From the beginning, we thought the best way to describe this is like a choose-your-own-adventure composition. Do you remember those books where you could go to any part and there were multiple ways the stories could unfold but all of them worked? That's kind of how we saw this. That was one of the jumping off points for us—if you could make a musical composition with multiple scenarios or outcomes where all of them worked. So the interesting part was that we were writing music like you would any normal album, but then trying to figure out how to technologically and organizationally make this work was a whole different challenge. So there's no narrative per se, but certainly the idea of choose your own adventure was a jumping off point for us.

NEA: Can you talk a little bit about the technology and data part of the project?

HOLLADAY: We are not really developers ourselves, and, while we definitely gained a bunch of skills throughout this process, we've worked with a lot of other people who collaborated with us on the tech side. The way it works in a very basic sense is very similar to the engine behind a video game. If you think about how a video game works, there's sound and music associated with different areas or objects within this virtual terrain that your avatar is moving through. So as you approach a waterfall in a video game, it’s increasing in volume based on your character's proximity to that waterfall. And the idea there is to give the illusion that you are in a physical space by mimicking how sound functions in the real world. What we’ve done is take this idea of syncing the coordinates of that virtual space and translated it to the coordinates of a physical space.

NEA: Do you consider yourself a musician or are you a sound-artist?

HOLLADAY: That is a good question. I think my background is certainly in music, and I think I moved laterally into the art world and probably don’t have the credentials to consider myself a professional in either field. But I think maybe what I’m bringing to the table is the sort of intersection of these different areas—music and technology, both in my work as a curator at Artisphere and my role in creating with my brother. That nexus where art and technology come together and create something that doesn't fall into either category or falls into both is at the heart of what Hays and I do together and is central to many of the projects that I’ve brought to exhibit at Artisphere. I think those labels are becoming less and less relevant with the kind of work that crosses these sorts of platforms now, these different genre-bending things. That’s the kind of stuff I’m interested in.

NEA: I’d like to as you now about your work as the new media curator for Artisphere. What does “new media” mean as an art category?

HOLLADAY: When I think about new media, it's works that are using emerging technologies in ways that we're not able to categorize yet exactly how or where they fit. So, new media becomes that sort of catch all.

NEA: How would you describe your curatorial philosophy?

HOLLADAY: I think a lot of the vision of Artisphere is to be an arts space that hits a broad sort of demographic. I think one of the mantras for us has always been [to be] an arts space for everyone. So I try to do a number of things. One is to find artwork that can hit people certainly on a cerebral level, but then there's also what I like to think of as a low barrier to entry as far as understanding and interacting with the work itself. So things like a giant etch-a-sketch…while they certainly have a very intellectual or even academic underpinning to them, it's the kind of thing that anyone, regardless of their background, can enjoy and interact with. I think the other philosophy here is really showcasing works of artists of national and international acclaim alongside local and emerging artists—giving a platform for people in the region to show their work but also bringing in the best things outside of our area, and showing those things simultaneously.

NEA: Can you tell us about the W3FI exhibit that was just at Artisphere?

HOLLADAY: W3FI is by two artists, Christopher Coleman and Laleh Mehran, from Colorado…. This is a digital experience based on the relationship between our online and offline selves. So to unpack that a little bit more, the things they are addressing with this [installation] is the idea of the Internet being this space…where we have this online persona that is very separate from our offline, physical self. And this results in this veil of anonymity that exists online that results in things like cyber bullying and things of that nature. What they are proposing is that we need to see that who we are online has ramifications in the physical world—both in the positive and negative ways…. So those are the ideas of going from being individuals that are alone on the Internet to recognizing that other people are individuals as well and then coming together to form what they call a new philosophy of how we see our online selves which is “We-Fi” - combining the word 'we’ and 'Wi-Fi’ to create “We-Fi.”

NEA: Who are some of the people working in new media you find particularly interesting or exciting?

HOLLADAY: For me, one of the most interesting artists right now is Christian Marclay, who did a work called The Clock. It’s one of the most important works that I've ever seen…. It's a video piece that runs for a full 24 hours. The way it works is that it's all compiled from film clips that have some sort of marker of time in it. That could be everything from It's a Wonderful Life to Forrest Gump. In those shots that [Marclay] took, you'll see a clock in the background that has that minute in it. So, it's literally a perfect clock. You can [watch the piece] and it will go from a quote from a '80s movie to something from the 1920s. It will be someone looking at their watch. But the whole thing is 'real time' and you just sit there and you're just in a trance watching this thing. It literally functions as a clock. I went in at 3:30 and left at 5:00 and I knew exactly what time it was when I left because it was on the screen.

NEA: Why was that piece so significant to you?

HOLLADAY: I think I'm always attracted to artists who do things that are really massive in scope. That was one of those works that it was unbelievable just to think of how it was created, how they went through so much film just to find these small snippets where someone was looking at a watch or there's a clock in the background. Just the amount of dedication it takes to pull off something like this. More than that, the work itself is actually beautiful. The way that he seams everything together, it almost feels like there is a narrative, even though there is not. I think it was a really ingenious way of repurposing [older material.] It’s the kind of thing that wouldn't have been possible before. We didn't have the tools available to us to cull from so many different places, all of this kind of data, all of this film that has now been archived. To me it was just this massive scale of this work amounting to something that was just so beautiful, and people would stay there for hours and hours and just be totally transfixed by this thing.

We've certainly had artists that have come in here that I think are doing really amazing things. For instance, on the more local level, we had an artist that just had a work in the Works-in-Progress Gallery. His name is Jonathan Monaghan and he does digital fabrication. [We’re showing some] video works based on designs he created, but he also does what's called 3D printing, which is a very new kind of emerging technology in of itself…. We had physical manifestations of [his video works] that he had printed out, sort of sculptures, and here's the really interesting part of this: at one point we asked “What should we do as far as security if somebody takes one of these?" and he was like "Oh, I will just print a new one out." I really loved having him here especially because I think it will be one of the more fascinating technologies going forward. I think it’s going to have a huge impact on how we create artwork and how we live our lives. The abilities to recreate a single sculpture as many times as you want really begs the question and the idea of scarcity in the art world of limited editions. When you can literally download a file and print out an exact replica of somebody's work, what does that mean for art, for sculpture?