Level Up!

Video games have come a long way since 1958 when William Higinbotham created Tennis for Two, nearly two decades before Atari was even a start-up. In summer 2012, the Smithsonian American Art Museum hosted the groundbreaking exhibit The Art of Video Games, and New York’s Museum of Modern Art closed out 2012 by accessioning several games into its permanent collection, including Pacman, Tetris, and Myst. Still, the NEA raised some eyebrows in 2012 when it encouraged potential grantees to consider projects involving video games. The problem? Not everyone seems to agree that video games are part of the arts.

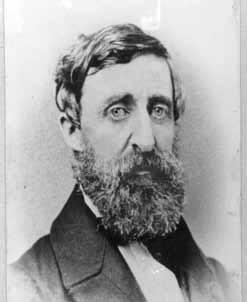

But let’s face it, without a visual artist, a musician, or a dancer on the team, there’d be no Angry Birds or Dance Dance Revolution. The agency’s grants to support video games indicate the crucial role artists play alongside technologists in creating games, while reflecting the agency’s support of innovative projects that fall outside the traditional boundaries of fine arts. Tracy Fullerton of the University of Southern California and Jan Norman of Young Audiences, Inc. (YA), both recent NEA grantees, know first-hand that arts are equally as important as technology whether you’re a game designer or a gamer. A classic work of art— Henry David Thoreau’s Walden—is the subject of Fullerton’s game in progress, while Young Audiences has adopted video game design as a strategy for rekindling a love of learning in young people while also engaging them in the fine arts. In both cases, the arts are front and center as game-changers.

DESIGNING A LOVE OF LEARNING

Norman, Young Audiences’ director of education, research, and professional development, described the mission of the 60-year-old organization as “[thinking] about what it is that we learn from the art-making and the art-thinking process that can help inform us, and make us better able to learn in other subjects.” Last year, YA piloted a two-part immersive game design curriculum intended to cultivate skills such as critical thinking and collaboration in young learners by asking them to create video games, and to equip educators with the necessary skills to facilitate student projects.

The program is rooted in the belief that “gamemaking is a composite of all the arts,” said Norman. “You can’t create a game without…looking at and using the visual arts to create the background, to create all of the things that make it exciting. You would likewise need to complement it with music and you also need to have good writing skills.”

Norman believes the curriculum not only develops specific fine arts skills, but also teaches “design thinking,” a critical skill in the 21st century. As Norman explained, design thinking is an iterative process that includes “identifying the intention, defining what resources you have, gathering information,…[and exploring] different possibilities through this reflective process and authentic assessment…. It’s essentially the exact same process that every designer goes through and that every artist goes through and that applies to any kind of learning in life.”

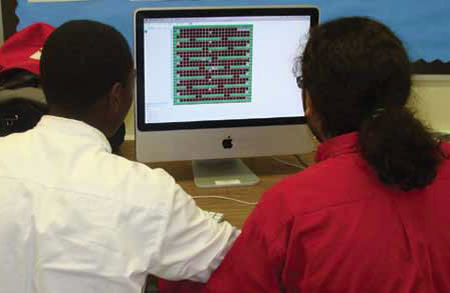

To borrow a phrase from the gaming world, YA’s project is “multi-player;” YA designed the program in tandem with Laguna College of Arts and Design(LCAD), working closely with Jack Lew, the college’s then-dean of visual communication, a former colleague of Norman’s, and in university relations and art talent recruiting at Electronic Arts. LCAD already boasted a summer game design program for local high schoolers, so the partners were able to build on that curriculum, incorporating the professional development aspect for teaching artists and classroom teachers. Both cohorts work in teams to learn all of the aspects of game design, from creating the look and sound of the game to writing the player “script” to programming.

Mentorship is a critical element of the project: the classroom-level teachers are mentored by professional game designers, the students are then mentored by the newly trained educators, and finally, as students acquire advanced skills, they, in turn, mentor each other and new students.

Another important element, according to Lew, is that the educators develop games around their particular school subject, which for one Kansas teacher was language arts. As Lew described, “The teacher was working with the students on developing a game or games related to what they were reading, which [was]Tom Sawyer. So the player actually had to gather information at different sites related to locations, like Hannibal, Missouri, within the story…. Even in that particular language-arts class, there would be certain graphics and visuals that the students had to create. They had to work with art and sound and programming and design thinking.”

The immersive game design project debuted at three YA affiliate sites—YA of Northeast Ohio, Arts Partners Wichita, and YA of Indiana—through a combination of summer, in-school, and after-school class time. By spring 2013, Norman expects the video game program will involve about 1,200 students. In fact, the Ohio program hopes to springboard into a game design-focused high school come fall. In addition to growing enrollment, YA is looking at various ways to measure the success of the project. “We want to see students not only learn to solve certain problems but to be aware of their learning. In other words, learning to learn with an ability to be articulate and explain what that learning is,” said Norman.

Lew added, “I want [students] to know that learning can be fun. I want them to know that engagement with subject matter that’s challenging can lead to some exciting results, and that good things don’t come easily.”

TAKING ON THE PERSONA OF THOREAU

If Lew is correct that a measure of success is engaging with challenging subject matter in pursuit of exciting results, then Tracy Fullerton’s Walden project is already a hit. What could be more challenging than making an interactive 21st-century video game out of a nearly 300-page, 19th-century text comprising equal parts philosophical treatise, nature guide, and outdoor-living manual? According to Fullerton, the idea for the game sparked while she was simultaneously visiting Walden Pond and reading Thoreau’s tome. “I started thinking about how his experiment was…a way of trying to understand the world and his place in it, and the changes that were going on around him.” Fullerton—an experimental game designer—was struck by the author’s articulation of what he considered the essentials in terms of his relationship with nature and with society. “The more I thought about that…the more it seemed like a really interesting and playable system, which I could express in a game and which a player could take on for themselves.”

Fullerton and her team, however, are not striving for a slavish recreation of the text. Rather they are working toward what Fullerton calls a “translation” ofWalden into a different aesthetic form. “You do begin in July, which is when he first went down to live at the pond, and the first thing you do is you build your cabin. So it does begin at the outset with the same sort of start of the adventure. But then we let you explore and play out the experiment on your own.” As the game progresses, the player—taking on the persona of Thoreau—has to satisfy basic tasks, such as chopping wood and picking berries, after which he or she can decide to make money, become an expert in the flora and fauna populating the landscape, or spend more time with the text excerpts embedded throughout the game. “Depending on how you decide to play the game, your relationship to the woods grows more lush and vivid and more inspired, if you will, or it can diminish and become quite banal if you, say, spend all your time working and not thinking about the larger picture.”

Given the level of detail achieved in the original text, building the game takes a wide range of skill sets. In addition to Fullerton, the creative director and designer, the team includes a programmer, a level designer, an environmental artist, animators, a sound designer, and even someone who was responsible for animating Thoreau’s hands—to enhance the first-person player experience—among others.

Like Fullerton, each member of the team—none of whom work on the project full-time—is fiercely committed to getting it right. She described part of their process: “We’re now building a procedural sound environment so that as you walk around the world, not only do the birds and sound of the world change, but they change according to the season, they change according to the time of day. They actually even change according to what kind of trees you’re standing around so that the right kind of bird calls are happening in the right kind of trees. Our sound designer, Michael Sweet, who’s amazing, lives onsite in Concord so he’s recording all of these during the course of the year.”

While the prospective audience for Walden the game is demographically broader than the target group of Young Audience’s project, both endeavors reflect a preoccupation with contextualizing learning in a way that makes it exciting for young people. “One of my original inspirations was younger people who may not have the patience to get through Thoreau without some incentive or some inspiration,” said Fullerton. “And if I can contextualize it, make them feel how exciting the kind of adventure is of going out and discovering these sorts of things that he was trying to understand about life and our relationship to nature and to basic systems, if I can make them feel it by playing a game, then they may be inspired to go and read the book and to think about these things in relation to their own life.”

Both projects also reflect the importance of arts thinking in strategizing a way to fruitfully engage with the world. “I could say that making games is my way of understanding the answers to questions that I have about the world,” mused Fullerton. “And that is one of the primary impulses of an artist, to use a medium to explore the central questions that intrigue them, that plague them, and that they think are of interest to themselves and others.”