Another Set of Hands

Most of the patients at Matheny Medical and Educational Center will never have the physical ability to leap across a stage or even grasp a paintbrush. Some will never form the words to recite a poem or a line of script from a screenplay. Individuals treated at the Peapack, New Jersey, facility live with exceptionally complex disabilities, from cerebral palsy to unusual conditions such as Wolf-Hirschhorn syndrome, rendering many quadriplegic and non-verbal. The most mundane of tasks, from eating to nose-blowing, require assistance, and both minor and major decisions are often yielded to caregivers by necessity.

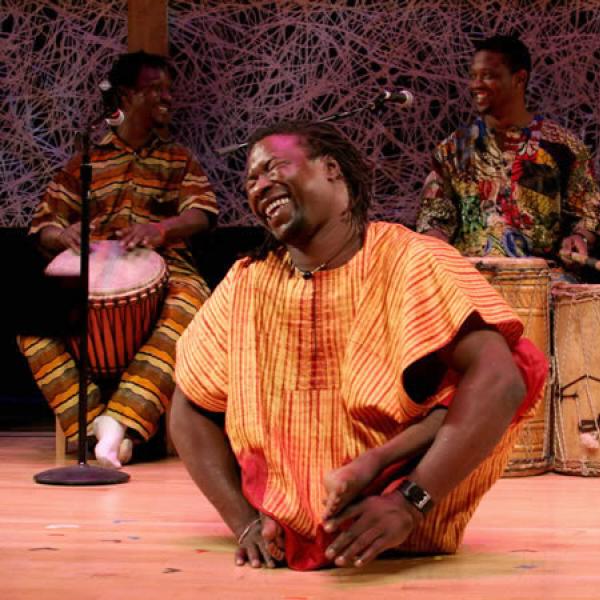

But the limits of their world dissolve once they enter the art studio. Through Matheny’s innovative Arts Access program, founded in 1993, patients have become painters, poets, playwrights, and choreographers. Their creative wishes are executed by “facilitators,” professional artists who serve as a neutral set of arms and legs whose actions are dictated by participants. “We’re a lot like computers in that we can’t do anything unless we’re specifically programmed to do it,” said Keith Garletts, Matheny’s outreach coordinator and program specialist. “The client artists program us, they tell us exactly what they want.”

The system has given individuals like Natalia Manning the ability to choreograph works, act and dance onstage, and create paintings, several of which have sold. Manning, who has cerebral palsy, uses a wheelchair and communicates through an iPad, which vocalizes the words she taps out one letter at a time. She grinned when asked what medium was her favorite, but demurred, saying, “each helps me in a different way.” Her artwork, she said, was a way for her to let people know “I am normal. I am like everybody else.”

To help artists like Manning convey the complexities of their artistic visions, Arts Access has developed a novel communication system. Every art form is broken down into its most basic forms, with visual menus presenting options such as brush size, stroke, color, and shape for painting, to filmed snippets of various dance movements for choreography. As long as artists possess yes/no communication, which might entail eye or eyebrow movements rather than words, they make every artistic choice, from the placement of actors on a stage to whether paint will be splattered or dabbed.

“[Facilitators] need to be able to offer infinite artistic choices in a manageable form,” said Arts Access Director Eileen Murray. “They bring their technical know-how and artist mindset in knowing that there are important questions to ask. It makes a difference if you want a size-two brush or a size-three brush.”

To maintain neutrality, questions cannot be framed in a leading manner, yet facilitators must continually seek affirmation. Do you want more paint on the brush? Is this how you want it to look? Does something need to change so it looks how you’d like it to? It is a painstaking and lengthy process, but one that has given new meaning to the concept of artistic freedom.

“They can direct the design of building a sculpture. They can direct the movement of a dancer onstage. They’re making these physical things happen. They’re controlling their environment,” said Kenneth Robey, the director of research at Matheny. For individuals without the use of their limbs, this is nothing short of seismic. Further, “they’re controlling the means through which they communicate their internal world to everybody.”

For non-verbal participants especially, who have no easy mechanism for self-expression, this is again revolutionary. “They’re expressing what we all want to express—their joy, their sadness, their pain,” said Murray. “It’s freedom and it’s liberty, and they’ve been deprived of it by the nature of their disability.”

The question for Robey was whether this sense of control over one’s physical and emotional worlds extended beyond the studio. In a study funded by the NEA’s Art Works: Research program, Robey and his team are looking at whether arts participation among disabled individuals is related to an increased sense of self-determination, and a stronger belief that they can dictate the events and outcomes of their lives rather than some external force. The study’s subjects include Arts Access participants and non-participants, as well as individuals at Hattie Larlham, an organization for disabled individuals in Ohio with a similar arts program.

Although final results won’t be analyzed for several months, Robey believes findings could be “good ammunition for arts programs in the never-ending search for funding,” and might encourage organizations for disabled individuals to install or expand arts programs of their own. But he noted that there are other benefits from Arts Access that are “painfully obvious,” to the point where no formal research is needed to appreciate them. The big one, he said, was self-esteem.

This is perhaps most evident during exhibitions and festivals of Arts Access’s work, including shows at Rutgers New Jersey Medical School, the Grounds for Sculpture sculpture garden, and the New Jersey Theatre Alliance’s Stages Festival. Arts Access also hosts an annual multidisciplinary showcase called Full Circle, which has received NEA funding.

“It’s one of the very few times in [these artists’] lives that they are the center of attention and they’re being applauded for who they are and what they’ve done,” said Murray. “There are so many life events that are important to us that we take for granted,” she said, citing graduations, new babies, first cars, and new homes. “These are all things that Matheny individuals don’t have and won’t have.

Through the arts, they are truly celebrated and they receive the acknowledgment and praise that they deserve.”

Beyond applause, these exhibitions and festivals offer Arts Access participants a chance to interact with the wider community in a way that’s typically difficult. Garletts noted that for individuals without significant disabilities, it’s relatively easy to form connections with others: we say hello to neighbors, we strike up conversations at bars or dinner parties, we join clubs or volunteer. Not only are such social interactions less likely for Matheny patients, but the aphorism that it’s not polite to stare often prompts a total avoidance of eye contact. “If a bunch of people are actively looking away from you,

you notice that,” said Garletts.

But no one is uncomfortable staring at and admiring a piece of art. Through this act, the conversation shifts, and becomes about the artwork rather than about a person’s physical condition. “When [audience members] see and experience the art, that’s a connection to the individual as a person and not as a person with a disability,” said Murray. Regardless of an artist’s verbal ability, “They can converse with that stranger who’s come to see their work. They converse with them through their art.”

Like most art shows, the events also function as a marketplace; part of the goal behind Arts Access is to provide vocational opportunities for individuals at Matheny. Garletts recalled a time a few years ago when an Arts Access artist excitedly told him that he had just sold a painting. “He just looked at me and said, ‘Man, you have no idea how good it feels to make a buck,’” Garletts remembered. “We take for granted the fact that we have the ability and privilege to work and hold a job.”

But for Arts Access participants, gaining recognition as a working artist is nothing to take lightly. Natalia Manning seems to agree. “Before Arts Access, I hated my life,” she said. “It showed me I can do anything.”

All photos courtesy of Matheny Arts Access Program