Arthur Mitchell

A product of the imperial courts of France and Russia, classical ballet is steeped in aristocratic ideals. Key to its history was a patrician vision of purity, uniformity, and whiteness. The courtiers, swans, sylphs, or snowflakes that populated the stage had to look alike and be fair-skinned. It is, unfortunately, a vision that has been hard to shake.

Ballet’s lack of diversity is beginning to change, as we’ve seen most recently with the promotion of Misty Copeland to principal dancer with American Ballet Theatre—the first African-American woman to hold the title. But her story begins with other artists who pushed at the barriers of race and color to realize their dreams of becoming classical ballet dancers. Perhaps most notable is Arthur Mitchell, who made his debut in 1955 as a member of the New York City Ballet.

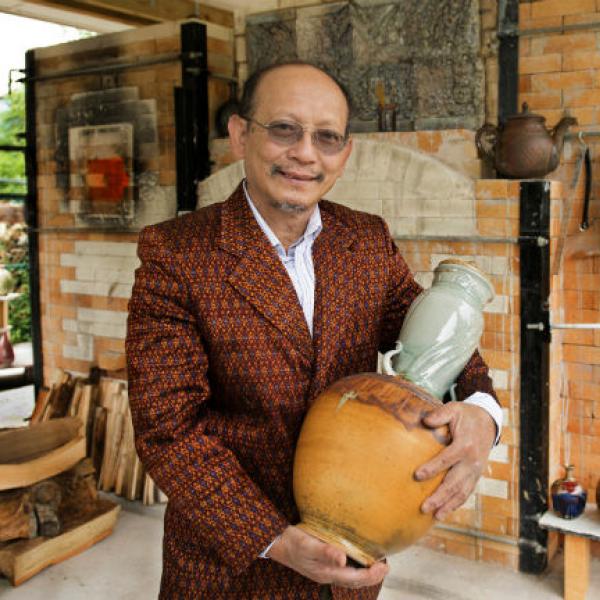

Mitchell was born in Harlem, New York, on March 27, 1934. As a young teenager, a guidance counselor encouraged him to audition for the High School of Performing Arts, which led to a scholarship to the School of American Ballet, the official school of the New York City Ballet. Mitchell joined the company, making his way through the ranks to principal dancer. In 1969, along with Karel Shook, Mitchell established the Dance Theatre of Harlem, which has won numerous NEA grants through the years. He remained the artistic director until 2004, when the company temporarily closed. In his own words, the 1995 National Medal of Arts winner describes what it has meant to be a black man in ballet.

STEPPIN’ OUT

I went to the High School of Performing Arts and when I auditioned, I prepared a tap dance routine to Fred Astaire’s “Steppin’ Out with My Baby.” But when I got to the audition, I saw all these trained dancers in modern dance and ballet. I thought, “I’ll never get in.” But they needed male dancers, as usual, and I got in. In addition to studying at the school, I danced with Donald McKayle’s company. I worked at the Choreographers Workshop, and with the New Dance Group.

In your senior year at Performing Arts, you did auditions, and that’s when I ran into racism, because I would see that I was the best dancer but I didn’t get the job. I kept saying, “Well, what can I do? What can I acquire that would make me so good people would use me regardless of my skin color?” So that made me decide to take the scholarship that was offered to me to the School of American Ballet. I hadn’t had ballet training before then.

When I got to the school, the only other people of color were Louis Johnson and Chita Rivera. I didn’t think of blazing a trail. I was just trying to get technique to get a job.

After three years at the school, from age 18 until 21, I felt that nothing was going to happen for me professionally. I thought I would try Europe because I had seen Roland Petit’s company, and there were a couple of black guys there. So when John Butler asked me if I wanted to go to Europe with his company, I said yes. I was in Europe touring when I got the wire from Lincoln Kirstein [New York City Ballet general director] asking me to join New York City Ballet in the corps de ballet. I left the tour and came back and joined the company in November of 1955.

|

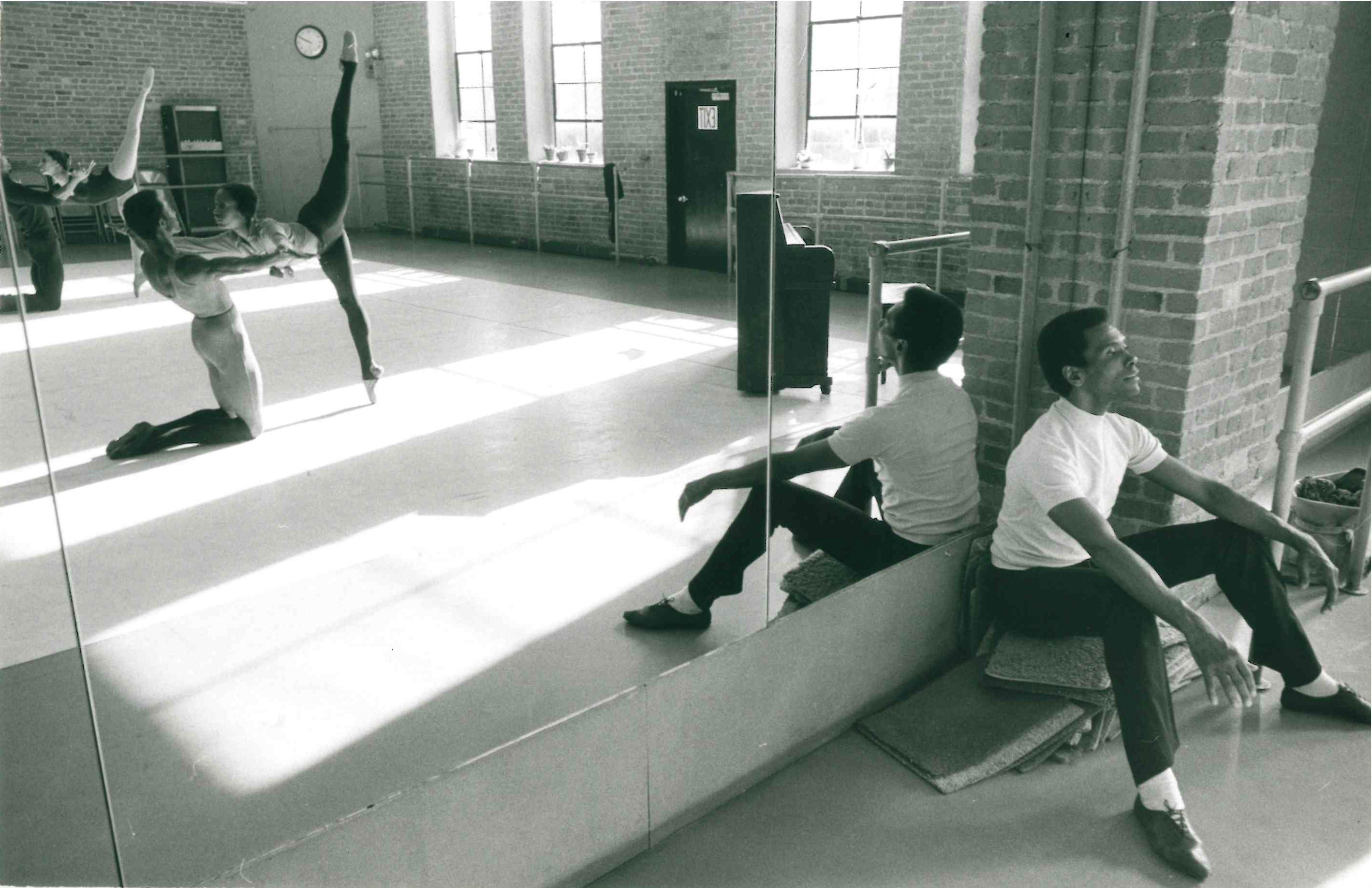

WORKING WITH BALANCHINE

When I was with the company, we performed at New York City Center, where they also used to do musicals all the time. I did Carmen Jones and I did Kiss Me, Kate because New York City Ballet didn’t work that many weeks a year. So there was always a mixture of training that I had. Since I was starting very late, any opportunity I could get to perform I would take.

At New York City Ballet, everybody was on my side, whatever we did. There were a couple of instances where we would do a television program and the producers said, “Well you can’t do that piece with the black guy.” [New York City Ballet artistic director and choreographer George] Balanchine said, “If Mitchell doesn’t dance, New York City Ballet doesn’t dance.” There were parents of some of the girls in the company who were upset about my dancing with their daughters, and Balanchine said, “Then take them out of the company.” So I danced in every ballet, in Swan Lake, in Nutcracker—everything. There weren’t roles that were consigned for black dancers. There were just roles for a dancer.

Balanchine’s Agon is an amazing ballet and the pas de deux in it that he set on me and Diana Adams is brilliant. He took a black man and Diana, who was very patrician, long legs, ivory white skin, in a pas de deux that is very intricate that involved serious partnering. The whole secret of that pas de deux is the woman must let me do everything to her. Balanchine used the masculine way I danced against her femininity. I do feel that skin color was part of the choreography. Agon doesn’t look the same if you see two white people doing it or two black people doing it. You see, my skin tone against her skin tone made a big difference.

I think Balanchine was quite fascinated with me as a dancer. For him to do what he did with me was really unbelievable, because this was before the civil rights movement. I think a lot of it was due to the fact that Balanchine came to this country and he was a foreigner. He knew what it was to have to go through challenges to be successful. He had worked with Josephine Baker in the ’20s and ’30s, and then also with Katherine Dunham. He always felt that New York City Ballet should be an American company, not a European company.

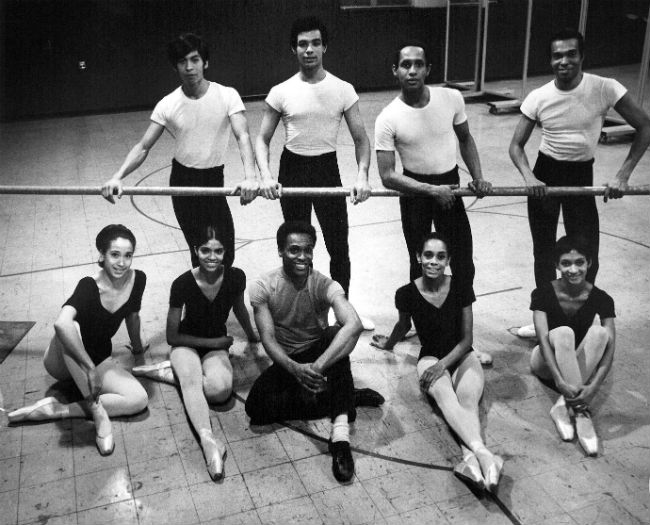

RETURNING TO HARLEM

I wanted to go back to the community where I was born, which was Harlem, and give the opportunity to young minority kids there in dance and classical ballet. So we started a school and then a company—you can’t do one without the other. It was called Dance Theatre of Harlem, not Ballet Theatre of Harlem, because it is theatrical dance grounded in classical ballet.

When I started the school I had two dancers and 30 children. In two months, I had 400 kids and in four months, I had 800 students, boys and girls. They wanted the structure and the discipline in their lives so badly, and I thought, I’ll be the one to give it to them.

I brought my company to Russia in 1988. It was one thing for the Russian dance audience to have seen me [when I performed there with New York City Ballet], but then to come back and bring my dancers—it blew the audiences’ minds because they had never seen anything like that. I’m not talking about Alvin Ailey or a modern dance company. I’m talking about a ballet company, and we had tremendous success.

In 1992, we went to South Africa. [Nelson] Mandela asked me to come, and that was when they were trying to banish apartheid. But I said, “You know Mr. Mandela, I don’t know if I could do this.” He said, “No, you will— everyone wants this to happen. I will get every faction in South Africa to sign something that nothing will happen to you.” Every faction in the country signed it, “Yes, we want this man to come.” He said, “Because Arthur, you’ve proven that any child, given the opportunity, will excel.”

I’d never been in a country where the black people were the majority not the minority. It was unbelievable for me and the company, because we saw where our ancestors came from.

The thing that I am most proud of regarding the company is the fact that it existed. Our repertoire was one of the best in the world because we had the best of Balanchine. Then when Mr. Shook passed away, we got Freddie Franklin [former principal dancer with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo] as an artistic consultant and we got the Diaghilev ballets, which had a great mystique. We did Les Noces [a ballet and musical composition by Igor Stravinsky]—can you imagine a black company doing that piece with the score sung in Russian? It was like a little United Nations of dance in a sense.

|

CREATING THE MELTING POT

You see, this is America, and to say, “Who’s an American?”—it’s black, white, Asian, Hispanic. It is a melting pot of people, and when people go to the theater, they want to see that on the stage. You’ve got to get new bodies to fill those seats. So the more interracial the audience is, the better off it’s going to be for that company, and that means you’re going to get better support.

One of the strengths of Dance Theatre of Harlem is that we must have done a thousand lecture demonstrations, going into communities that had not seen ballet or didn’t even know anything about it. They said Dance Theatre of Harlem is like a traveling university. Now you find basketball players, football players—they all are studying ballet. It’s the strongest technical base to make you better. Consequently, all those things add together to make for greater awareness of the art form.