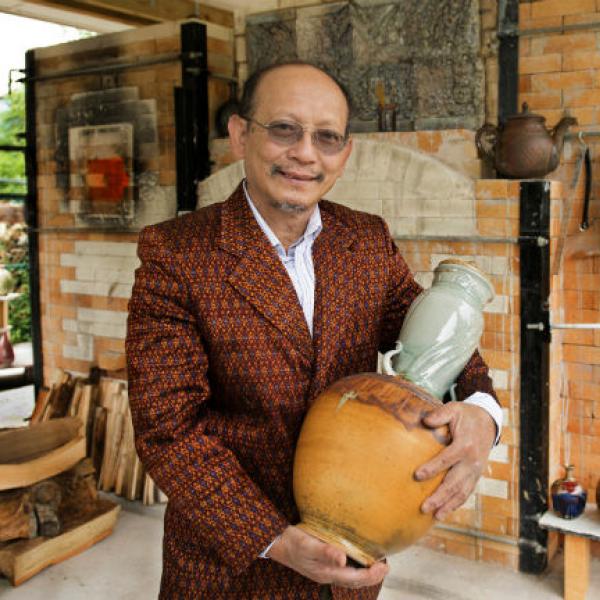

Lin-Manuel Miranda

Lin-Manuel Miranda is on a roll. Already a Grammy, Emmy, and Tony Award winner (among other awards), Miranda received a MacArthur Foundation Award in 2015, the same year his current musical, Hamilton, opened on Broadway to sold-out crowds. His soundtrack to the musical—a hip-hop riff on Alexander Hamilton’s life—took home a Grammy in 2016, and the play continues to draw huge audiences in New York. His first musical, In the Heights, also a Grammy Award winner, took home four Tony Awards in 2008. Miranda co-wrote the music and lyrics for Bring It On: The Musical with Tom Kitt and Amanda Green, which opened in 2011. Additionally, Miranda is a co-founder and member of Freestyle Love Supreme, a popular hip-hop improv group that performs regularly in New York City. Josephine Reed talked with Miranda in New York City in February 2016 during the run of Hamilton. His thoughts on his two award-winning works, and the state of theater today, are below. The podcasts can be heard here.

WRITING ABOUT THE NEIGHBORHOOD

Rent came out when I was 17—I saw it on my 17th birthday, 1997. Suddenly, here I was seeing a musical that took place not in a far-off land, or in a far-off country, but in the West Village with people struggling whether to stay in the arts or sell out. People struggling with disease, struggling with poverty. It was the New York struggle in musical form, and it took place now. I think that tacitly gave me permission to write about what I knew. I knew I loved the musical form, but [Rent] told me, “You can write musicals. That’s not something that only a few people have access to. You can write about it, too.” Because Jonathan Larson [author of Rent] was writing about his friends. And that is valid. That is a valid evening in the theater.

That connects to In the Heights very directly, because my first attempt at a full-length musical was In the Heights. It was everything I’d always wanted to see in a musical. It was Latino characters. I was also empowered by the fact that I was living in a house with other Latino students at the time.

I spoke Spanish at home and English at school. In the Heights was really the first time I’d brought my culture from home to school in a very real way, to write about the neighborhood I grew up in, or at least adjacent to. I grew up north of Washington Heights. I wanted it to sound like my neighborhood. So I’m dabbling in the Latin forms that I grew up with around the house, but also playing with hip-hop and playing with musical theater, and just trying to bring all of myself to it.

When In the Heights went pro is when I met [director] Tommy Kail, who by all accounts is smarter than me and had 50 ideas of how to make the musical better. Then we found the people who could help us really bring it to life, and that was Alex Lacamoire, our music director, and crucially, Quiara Hudes, our book writer, who had the same upbringing and schism growing up in northern Philly that I did in northern Manhattan. We really doubled down on, “Okay, let’s make this about our community, and a love letter to the communities we grew up in.” Not about the drug dealer on the corner—that guy is on the corner, as he is in every neighborhood in America—but the hard-working local businessmen, who came from another country, who works at the store inside the corner, who makes Washington Heights unique and stand out.

|

THE EFFECT OF IN THE HEIGHTS

I saw what [In the Heights] did to Latinos who finally saw themselves represented on the stage in a way that wasn’t holding a knife. Over the years, the show has gone to stock and amateur, and people have done high school and college productions of the show. I can’t tell you how many times I’ve spoken at a college and I get kids—male and female—come up to me and say, “Nina Rosario is about me!” That’s been unbelievably heartening and validating.

Nina is the one who went to Stanford, lost her scholarship, and has pretty much given up at the top of the show, and leaves with a resolve to go back. I don’t think we tell that story a lot. You don’t see, “My parents really worked hard for me to do something, and I’m going to honor that. I’m going to honor their sacrifice.” As a kid of parents who both were born in Puerto Rico and came here, I was so aware of the sacrifices they were making. It’s not a story that gets told a lot—at least not in mainstream culture, not in movies and plays. You see it in the news, but you don’t see it in a show.

ON WRITING HAMILTON

[Alexander Hamilton] writes his way out of poverty. He writes his way into the war through just a war of ideas. He writes his way into [George] Washington’s good graces. He also writes his way into trouble—at every step of the way, when cooler heads are not around him to prevail. I immediately made the leap to a hip-hop artist writing about his circumstances and transcending them. There’s also that self-destructive [nature]. You see rappers who have billions of dollars getting into wars of words with other rappers. It’s a part of that verbal one-upmanship. Hamilton is no different than that.

I chased the lyrical density of my favorite hip-hop albums, which you don’t always get in a musical theater album, because you’re worried about everyone getting everything the first time. You’re telling a story first and foremost, but what I love about my favorite hip-hop albums is that I’ll catch a double entendre I didn’t catch the first time or some alliteration or some word play. Years later I’m still catching it, because that’s the art form.

What I recognized in Hamilton, which connected me to the genre of hip-hop and the hip-hop culture, was his relentlessness. I recognize that relentlessness in people I know. Not only in my father who came here at the age of 18 to get his education and never went back home, just like Hamilton, but also so many immigrant stories I know, and friends I know who come here from another country. They know they have to work twice as hard to get half as far. That’s just the deal—that’s the price of admission to our country.

|

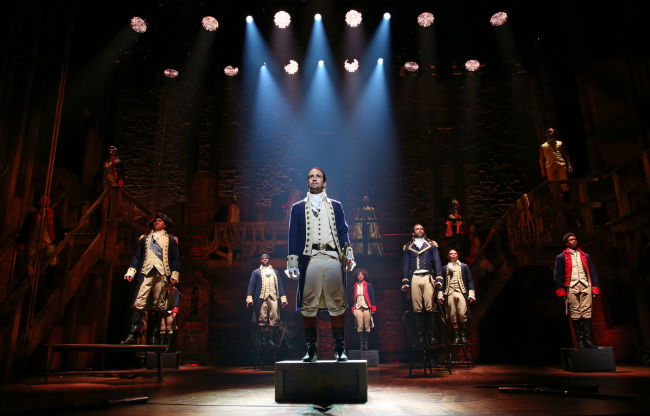

CASTING THE SHOW

The impulse of the piece was that you can draw a direct line between Hamilton’s life and the life of the hip-hop artists I grew up revering. So to that end, why wouldn’t our show look like hip-hop culture? In that initial read of the book, I was never picturing Founding Fathers. I was picturing what artist could play George Washington, what artist could play Hercules Mulligan—the guy never drafted a piece of legislation, but it’s the best rapper name I’ve ever heard. So that was always a part of the initial inspiration.

The genre of music lends itself to this type of casting, and it’s also the added sense of, “These people are like you and me.” It’s only amplified by the fact that we have every color represented on that stage. It eliminates distance between us and the story of our founders. It helps them feel more human to us, because it’s what our country looks like now. We never threw around the terms “colorblind” or “color-conscious.” That’s how it shook out—it was always with an eye towards, “Let’s get the best actors for these characters and these songs,” and that’s what we got.

WHY HAMILTON IS SUCCESSFUL

I had to make [the Founding Fathers] human for myself, and I think what is touching a nerve is other people are finding the humanity within them as well. They leave with an understanding, or at least a partial understanding, of what they were like as people in some weird way. You don’t get that when you look at a statue of someone or you look at their picture on currency. Regardless of your political stripe, to be connected to your country in any meaningful way, or its country’s founders—even if you leave [thinking], “Oh, Jefferson was a jerk,” or “Hamilton was cheating on his wife,”—you can’t dismiss them. You have to reckon with them, because we live in their country.

The other thing about the show is that the fights they have in the show—the ideological fights, anyway—are the fights we’re still having. How often do we get involved in the affairs of other countries? When are we states and when are we one nation? What is the role of government in our lives? Is it big or is it small? It’s not an accident that almost every character in our show dies as a result of gun violence. There are things in the foundation of our country with which we will always be grappling.

THE NEW DIVERSITY

We are, by incredible good luck, in one of the most diverse seasons in the history of Broadway. It’s Allegiance, it’s On Your Feet!, it’s The Color Purple. I do hope that the financial success of On Your Feet!, the financial success of Hamilton, empowers producers to say, “Hey, this is actually good business. It’s good business to have diverse casts. It’s good business to have diverse stories,” because that brings in a newer audience and engages us in a different way. That’s the only thing that really works— it’s got to be good business. Broadway is expensive. It’s expensive to mount a show. So the fact that not only are the shows here but [are] doing well is really what gives me hope, because it means there’s going to be more. Tomorrow there’ll be more of us.