A Culture of Survival

A display of katsina dolls at the Museum of Northern Arizona’s Hopi Festival. The closure and cancellation of markets, galleries, and festivals— including the 2020 Hopi Festival—has had a devastating effect on Indigenous artists. Photo by flickr user AI_ HikesAZ

Bob Rhodes recalled a moment several months ago, when a mentor from Hopitutuqaki, an art school that teaches traditional Hopi art forms, called the school’s office in tears. The woman had just received an unexpected $1,200 check, which represented her salary from the classes she had been scheduled to teach at the school last spring, all of which had been canceled due to COVID-19. Made possible by CARES Act funding from the National Endowment for the Arts, the check proved critical to the woman’s overall security. Without the check, “They would’ve had a hard time,” Rhodes said, noting that the sum amounted to a second stimulus check. “That extra $1,200 made a huge difference to them.”

Located in Kykotsmovi, Arizona, the heart of the Hopi Nation, Hopitutuqaki was founded by Rhodes in 2002; he retired as the school’s facilitator, or chief administrative officer, in September. Although Hopi culture has endured for well over a thousand years—Oraibi, one of 12 Hopi villages spread across three mesas, is considered the oldest continuously occupied community in the United States—there are aspects that continue to be endangered, most notably its language and several art forms, such as the Third Mesa style of basket weaving. Rhodes started the school to counteract these losses, and to preserve traditional Hopi craft processes.

Today, Hopitutuqaki offers a language-immersion preschool for three- and four-year-olds every summer, as well as classes that run from March through October that teach art forms such as moccasin making, basket weaving, garment making, and Hopi food preparation.

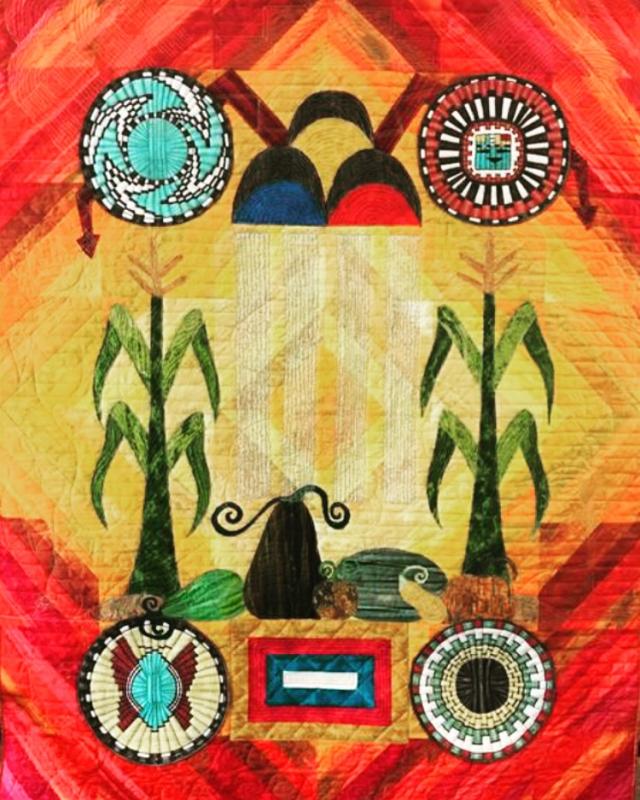

An opportunity quilt created by Hopitutuqaiki students. Photo by Robert Rhodes

With the school’s closure throughout the pandemic, the economic and cultural losses have been profound. For the preschool, four-year-olds who missed this summer’s classes will have aged out of the program by next year, which means losing one of the region’s primary opportunities for early Hopi language instruction. An estimated 5,000 people speak Hopi today, with younger generations much less likely to speak the language fluently than their elders. According to the 1997 Hopi Language Assessment Project, only 5 percent of youth under 19 spoke Hopi fluently.

“The more you hear it, the more you speak it, the better you can retain it,” said Donna Humetewa Kaye, a board member, office manager, and arts mentor at Hopitutuqaki who teaches sewing and garment making. “The older we get, the less we’re able to do that unless we speak it every day and use the language. It was a really big loss not to have the language program this year.”

The cancellation of arts classes also disrupted what have become critical ways of passing on traditional knowledge. Although Hopitutuqaki initially experimented with moving classes to online platforms, the reservation’s internet network ultimately proved too feeble, an example of how internet equity issues have impacted education in newly dire ways throughout the pandemic. “The system is not robust enough to support it,” said Rhodes, adding that people were getting dropped off of sessions, were unable to hear the audio, or simply weren’t able to log on.

A Hopitutuqaiki student learns how to weave a traditional Hopi belt. Photo by Robert Rhodes

But even if internet connectivity were not an issue, many of the art forms taught at Hopitutuqaki would be difficult to teach online. “If you’re trying to see where somebody was weaving something and did a mistake, then you have to be there,” Rhodes said. “It’s really difficult unless you’re one-on-one.” To be able to offer the same kind of visual guidance allowed by in-person learning would require a TV studio-style setup, he said, with specialized cameras and tripods. “We don’t have any of that kind of thing. Most of our students would be trying to do it on their phones.”

The economic fallout from the classes’ cancellation has also rippled through every layer of the school’s community. With the loss of tuition, Rhodes is unsure whether the school would have survived without the CARES grant, which covered the salaries of the school’s two employees—at the time, himself and Kaye—and allowed the school to meet its obligations to the mentors it had already contracted for the season. This was a lifeline for a number of mentors, many of whom make their living as artists. Leia Maahs, managing director of the Tucson-based Southwest Folklife Alliance—another Arts Endowment CARES grantee—noted that in a survey of folk and traditional artists conducted over the summer, 80 percent of respondents described finances as their most pressing pandemic-related concern.

Along with the school’s closure, the loss of tourism has been a major economic stressor for mentors and other Hopi artists. In an effort to protect its citizens from the coronavirus, the Hopi Nation has been closed to tourists since March. The move seems to have helped keep case counts relatively low: at the time of publication, there have been roughly 540 cases of coronavirus among members of the Hopi Tribe, despite the community’s location in the midst of the Navajo Nation. The Navajo Nation was one of the hardest-hit communities in all of Arizona, which was itself a global coronavirus epicenter over the summer.

At the same time, tourists represent a major source of income for Hopi artists, both on the reservation itself and in nearby towns. “Artists are used to being able to sell things to local trading posts, and even trading posts in nearby towns, including Phoenix and Santa Fe and Scottsdale,” said Rhodes, who noted that an estimated 60 percent of Hopi earn some or all of their income from the arts. “Those places aren’t buying because they don’t have tourists, and on the reservations they don’t have tourists because the reservations are still closed.”

This has been compounded by the cancellation of in-person markets such as the Santa Fe Indian Market, as well as the cancellation of traditional ceremonies, when artists typically sell ceremonial regalia and other specialty items to participants.

Pre-COVID, markets like this one in Santa Fe were a major source of revenue for Indigenous artists, Hopi included. Most markets were canceled this year, or were moved to virtual platforms. Photo by flickr user Betsy Weber

Moving to online platforms has been challenging for many older artists nationwide, Hopi included. In order to succeed in a digital marketplace, “You have to have a website or Instagram or some other way of promoting your artwork,” said Kaye. “Some of our people are old-school, where technology is really a hard thing,” she said, a difficulty that isn’t helped by broadband connectivity issues. There is also a degree of wariness for some, said Maahs, due to how prevalent intellectual property theft has become through the internet. Posting jewelry or katsina dolls online, for example, has made it easy for profiteers to design and sell knockoffs, which are then marketed as “authentic.”

In addition to mentors, the closure of Hopitutuqaki has also had economic outcomes for the school’s students. “When a student takes a class, our research shows that 30 percent of those students go on to produce work that then is either sold or used ceremonially or for family members,” said Rhodes. “It’s an economic boon to them, because if they didn't have it for ceremonial purposes, they would have to buy it from someplace else. So it either saves them money or makes them money.”

Although the pandemic shows no signs of slowing, Hopitutuqaki’s CARES award has allowed the school to persevere, and to once again begin serving the community. In October, Hopitutuqaki re-commenced classes, offering belt-weaving and basket-weaving in small, socially distanced groups where masks were required and sanitization was frequent. If the classes are able to operate successfully, additional classes might be added to the schedule as well.

While there will continue to be challenges in the coming months, Kaye for one prefers to take the long view, and look for signs of hope. “As Native people, we have survived all kinds of historical traumas and this is just another one,” she said. She had recently visited one of Hopitutuqaki’s older mentors, who was busy tending her corn, sorting beans, and performing the traditional duties that have patterned Hopi lives for centuries. “There are people that are carrying on. They’re not letting this virus hold them back from taking care of their families and doing what they need to do. Our culture has a lot of survival and, of course, prayer, songs, and storytelling, to remind us of who we are and that not everything is all doom and gloom. We’re going to get through this.”