What Light through Yonder Correctional Facility Window Breaks?

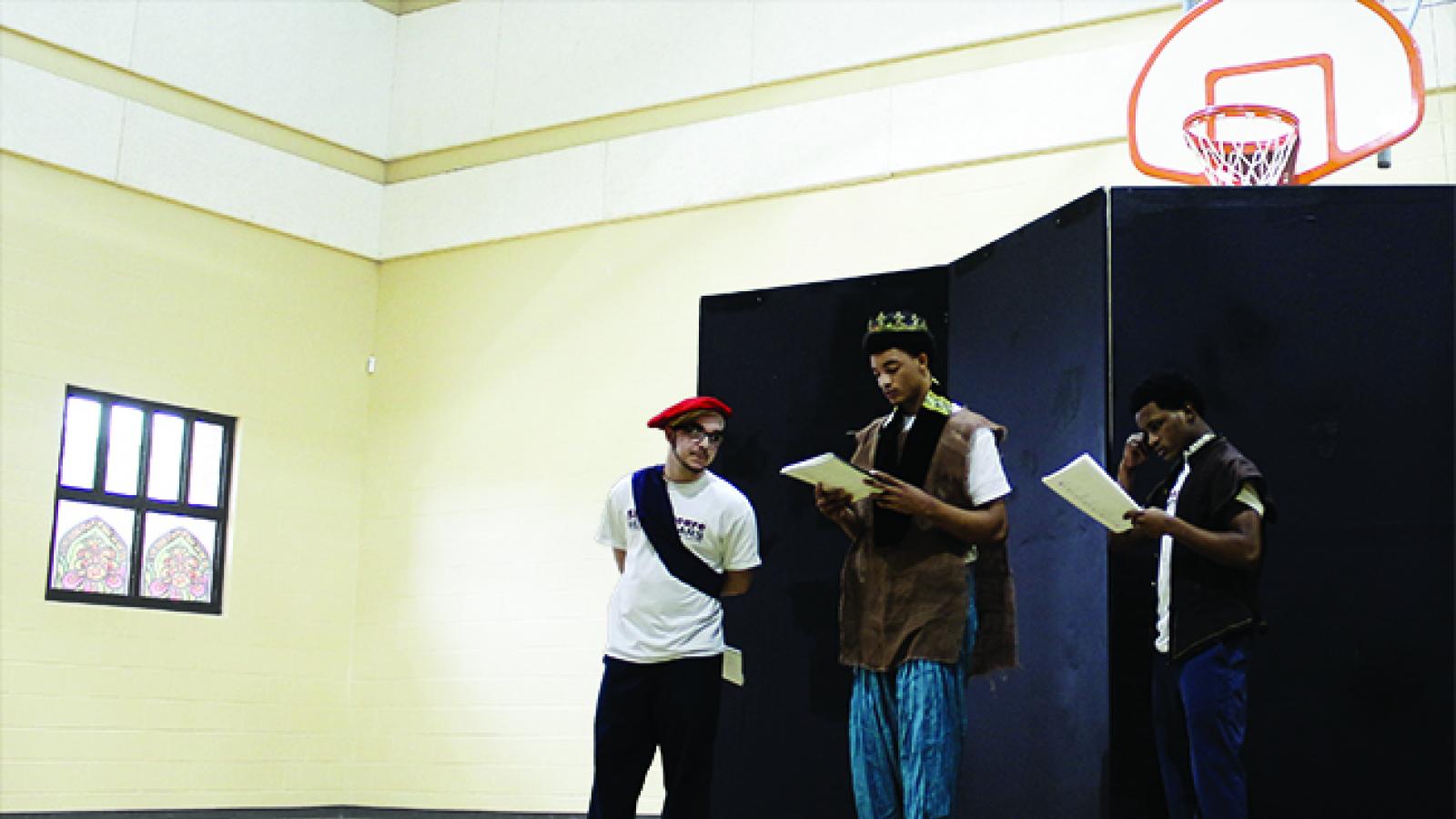

Youth perform a scene with Shakespeare Behind Bars. Photo by Holly Stone

When Shakespeare was writing Romeo and Juliet, there was no way for him to know that in a few hundred years, his tragedy would become an educational resource and inspiration for millions of teachers and students, much less for youth in detention centers.

Yet, that’s happening every year thanks to Shakespeare in American Communities, a national initiative funded by the National Endowment for the Arts and administered by Arts Midwest. The program brings Shakespeare performances and educational activities to thousands of disadvantaged students across the nation, including those in the juvenile justice system.

Shakespeare in American Communities launched in 2003, funding touring activities of seven Shakespeare companies that performed across the United States and at military bases. The initiative has since evolved into a youth-based program in which professional Shakespeare companies perform for middle-and high-school students and collaborate with educators to integrate Shakespeare-oriented activities into the academic curriculum. This year, the initiative has also reintroduced a juvenile justice component, which will allow eight companies to serve youth in juvenile corrections facilities through activities such as acting workshops, text analysis, theater games, and performances by participating youth.

For young people living in detention facilities, theater lends itself to rehabilitation because it requires actors to understand the identity and truth of the characters they portray. Furthermore, prison theater-arts practitioners find that Shakespeare’s deep understanding of the human condition allows incarcerated youth to identify themselves in his plays. In this way, Shakespeare inspires young people in juvenile justice facilities—many of whom are healing from traumatic experiences—to explore their own growth and their own voices.

“The reason that I use art, theater, the works of William Shakespeare, and original writing is that trauma can’t heal until the human being who’s experienced it finds language for it,” said Curt Tofteland, founder of Shakespeare Behind Bars, which recently received a Shakespeare in American Communities grant. “Shakespeare gives them language, and then as we rehearse, and as we talk about what’s happening to each individual, eventually they begin to find their own language for their trauma, and that’s when healing can happen.”

Tofteland discovered his passion for prison arts while performing one-man shows and conducting workshops at Luther Luckett Correctional Complex in Kentucky. He founded Shakespeare Behind Bars in 1995 while serving as producing artistic director of Kentucky Shakespeare. This will be his 25th year working in corrections.

|

Through the Shakespeare in American Communities grant, Tofteland plans to study a medley of Shakespeare’s texts with boys ages 12-18 from September to December at the Illinois Youth Center in Chicago. At the end of the program, there will be a performance for the facility, invited guests, and family. This will be Tofteland’s first time working in Chicago; most of his experience has been with incarcerated juveniles and adults in facilities in Kentucky and Michigan.

Connecting with youth in the justice system, especially in an unfamiliar city, requires prison-arts practitioners to bridge major social differences between them and the teens they serve. According to Tofteland, the key is to create a safe space for the boys to share their stories. Importantly, he notes that he and his staff go into justice facilities not to “fix” incarcerated youth, but to listen to them.

“It has to do with building a circle of trust, and most of the individuals that we deal with have had their trust violated,” he said. “They, in turn, often have violated the trust of others, and so it’s really going back and creating a family, creating a community, that is nonjudgmental and has unconditional love and is deeply interested in them.”

Another veteran prison-arts educator, Michael Forden Walker, echoes the need for practitioners to meet youth where they are. Walker is the director of youth programs at Actors’ Shakespeare Project, based in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which recently received grants for both the juvenile justice and school components of Shakespeare in American Communities.

“It’s incredibly important to really want to see and hear these young people because they often hide in plain sight,” said Walker. “What we try to do is just give them an opportunity to speak and be seen using both their own language and Shakespeare’s language.”

With the Shakespeare in American Communities grant period spanning the entire academic year, the Actors’ Shakespeare Project hopes to weave itself into the fabric of the community and give their teens meaningful exposure to multiple Shakespeare plays. Longer residencies also afford students more time to acquaint themselves with Shakespeare’s language and characters.

“Shakespeare obviously provides us with characters who are fully and brutally honest about what they need, want, care about, dislike,” said Walker. “Identifying with a Shakespearean character, and being able to use that identification to further reflect on your own experience and circumstances is an achievement that you can see they feel.”

Arts-based programs like Shakespeare in American Communities also offer hope to incarcerated youth and their families, not only because they provide powerful tools for self-reflection but because they are associated with lower rates of recidivism.

A youth plays Titus in a production of Titus Andronicus with the Actors Shakespeare Project. Photo by Nile Scott Studios |

“The participants in our program act differently, and their behavior is observably different,” said Tofteland. Shakespeare Behind Bars boasts a recidivism rate of 6 percent; the national recidivism rate is over 76 percent. “The only way that you can address change is for the person who’s committed the crime to go back and understand where the crime came from,” he said, explaining that this self-examination allows individuals to dig into who they want to become.

But the juvenile justice program is not the only piece of Shakespeare in American Communities that serves as a vehicle for introspection. The school component gives students a platform to connect with Shakespeare’s characters, and in turn, develop a deeper sense of their humanity.

“There are moments of true discovery,” says Adam Perry, vice president of strategy and programs at Arts Midwest, the regional arts organization that is responsible for administering Shakespeare in American Communities grants. “Kids grow and they grow together because they’re experiencing [live Shakespeare] with each other; they’re not isolated, and their face isn’t in an iPad for two hours,” he said.

The school component requires grantees to perform at ten or more schools, the majority of which must educate students who lack access to the arts due to being historically underrepresented, disabled, economically disadvantaged, or geographically disadvantaged.

This means that thousands of students receive access to high-quality Shakespeare performances and educational workshops who otherwise wouldn’t have had the opportunity.

Educational activities vary by company, school district, and the chosen play. For example, Actors’ Shakespeare Project, working within the Boston public school system, brings Shakespeare Words and Tactics, or SWAT, workshops to schools to prepare students for the Shakespeare performance. In these workshops, company members administer a variety of activities, such as acquainting students with Shakespearean language.

In combining the workshop preparation with the performance, companies like Actors’ Shakespeare Project ensure that the theatrical element of Shakespeare is not lost in the classroom, where much of the time is spent on reading the plays and writing essays about them, rather than performance.

“We go into classrooms and partner with [English and language arts] teachers and get the texts of Shakespeare off of desks and slowly into the bodies of the students,” said Mara Sidmore, director of education programs, projects, and partnerships at Actors’ Shakespeare Project. “A lot of these young people have not had their voices fully expressed and/or heard before in their lives. Many of them are living with challenging conditions in the inner city, and we want them to have a platform from which they can feel like they are seen and heard.”

This opportunity to be seen and heard— and to see and hear others—lies at the heart of Shakespeare in American Communities, regardless of whether it’s taking place in a school or juvenile justice setting. According to Tofteland, the program will give him, his staff, and the youth he serves the opportunity to exercise compassion for themselves and others. “To give voice to our suffering, to listen deeply to others, to find ourselves in another human being’s story,” Tofteland said, is what the grant is all about.

Antonella Nicholas was an intern in the Office of Public Affairs at the National Endowment for the Arts in summer 2019.