Jeanne Gang

In a 2011 interview with architect Jeanne Gang, the New York Times praised the newly minted MacArthur Fellow’s “habit of coaxing lyricism out of rigor in many of her designs.” It is this ability to balance beauty with utility that has made Studio Gang Architects, which Gang founded in 1997, one of the most exciting architectural firms in the country. Based in Chicago, Studio Gang has helped reshape the city with projects such as the 82-story, ripple-skinned Aqua Tower, a nature boardwalk at the Lincoln Park Zoo, and a pair of boathouses along the Chicago River, the latest in a series of steps to transform the neglected riverfront into a recreational area. During a recent phone conversation, Gang spoke about her creative process and shared the inspiration behind several of her projects.

Seeking Inspiration

One way I get started [on a project] is usually by creating a reading list of research around a topic that we might be dealing with. That reading list is added to by people that are participating in the project, including the client. That reading list builds up and it is a thing that creates a common baseline knowledge about the subject matter. So many times, inspiration comes from just reading about a subject and where the mind starts to take you. It starts getting more and more exciting the more that you build up that knowledge base.

The other kind of inspiration comes when you are not really trying, and you are just experiencing the city or something in nature; it is from direct observation of the world around you. A lot of times, for me, it is the natural world or a phenomena that I come into contact with—whether it is a storm or some kind of biological occurrence or animal or nature or something in a museum—those kind of things. Those terrestrial things are oftentimes very important and interesting to me.

Definitely, there are people that inspire me. Many times it is in these allied, but different professions or fields when I can suddenly make connections and synthesize information about my own knowledge or what we are doing at the studio with something that might be happening in the sciences or in urban planning or even in policy. Those are where the exciting synapses happen with me. And making sure that you have opportunities to be exposed to those different things. I love going to listen to architects, but I especially like to go outside the field and see what is going on, especially in the arts and in science.

Inspiration for Designing the Writers Theatre Building

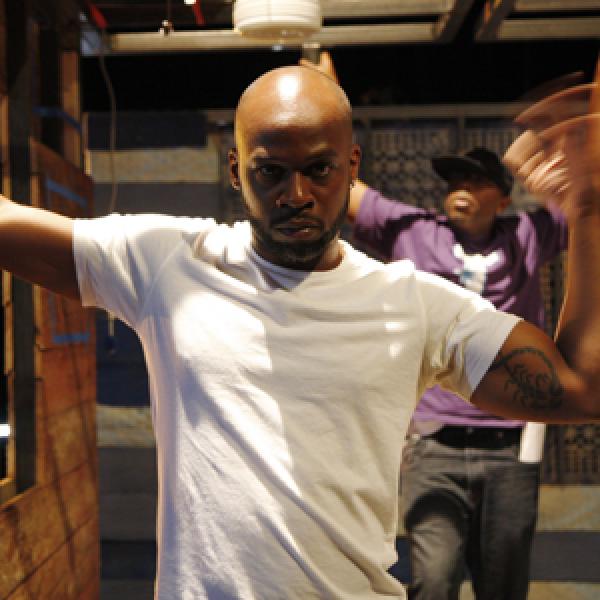

With Writers Theatre [in Glencoe, Illinois], the inspiration came from delving deeper into how theater could positively impact street life, and making connections between a specific place and something from theater’s past. Inspiration came from doing a lot of research and going to a lot of performances, which is a nice benefit about doing a theater project.

I was really inspired by the art itself, the productions that the Writers Theatre creates, and the way that they do it, which really gives a strong emphasis to the written word. The way that they craft their performances was, I thought, aligned with or parallel to the way that we create architecture and focus on the essence of the place, material, and environment as our medium to express. It’s relevant that theater historically was used to reflect society, create community, and enliven public space, particularly street theaters in medieval times.

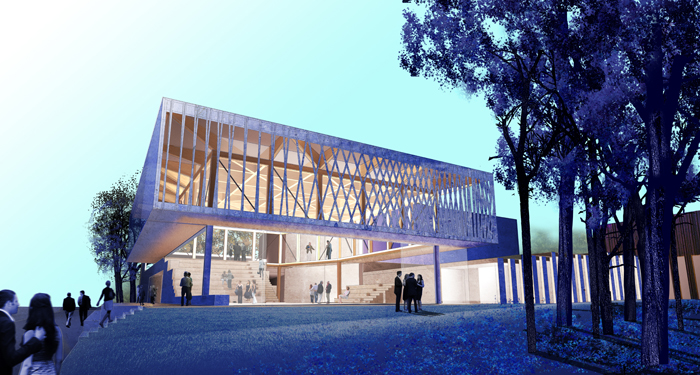

Glencoe was a place that was once a forest and then deforested and then [the forest] started growing back again. It had this need for a more lively downtown. We started putting together some of those dots and decided on the use of wood technology, inspired by the early frame type buildings of the Tudor era. So we were saying let’s take some of those past ingredients and bring them up to the 21st century and see what we can produce. It was not in any way trying to aesthetically copy anything in the past, but it was just finding these kind of touch points.

We ended up designing a space that actually gives Glencoe almost an impromptu theater space in the lobby, in addition to a thrust stage for 250 people and a 99-seat flexible black box stage. This lobby doubles as a performance space really much more connected to the street. It also gives multiple vantage points through this almost public gallery walk on the second level, where we are using wood construction, but a 21st-century version of wood construction, putting this piece of the design as a visible icon for the theater.

Carp: An Unlikely Source of Inspiration

Inspiration can also be found in something as troubled as the Chicago River, which was the catalyst for one of our major undertakings, Reverse Effect, the book we published in collaboration with the National Resource Defense Council (NRDC) after talking with them about the idea of placing a barrier in the Chicago River. The barrier would reestablish the separation between the Chicago River watershed and the Des Plaines and Mississippi Rivers watershed and prevent invasive carp species from entering the Great Lakes. It is kind of bizarre to be inspired by the threat of carp, but once we started looking deeper into the problem, there were so many aspects to it. The complexity of it was really exciting.

These carp are really scary. They jump out of the water when boats come by, and they are threatening to the whole recreational industry in the Great Lakes area. Also, they are filter feeders, so the threat is that they would wipe out a lot of the major fish populations in the Great Lakes, because they would be taking a food source.

Addressing this problem has the potential to affect the entire Great Lakes area, while at the same time encouraging the city of Chicago to reclaim land along the riverfront and remediate the post-industrial landscape. This in turn could have an impact on a small scale by reducing flooding within the city and on a larger scale by improving water quality. The Reverse Effect publication is meant to advocate for the issues surrounding the river and rally the public to take action. As a result of this advocacy work, we were commissioned to design the recently completed WMS Boathouse at Clark Park on the north branch of the Chicago River, increasing the public’s access to this important resource while highlighting the need to care for it. This boathouse follows the trajectory of our work with the river here and also has been inspiring to me to think about other cities and their postindustrial waterfront and their river health, and how that has an impact on how the city develops.

Inspiring Others to Live in a More Compact City

I think the most important thing has been to make architecture that is engaging to the city, to make the city a compelling place so that people want to be living in a more compact city. For example, something like the Aqua Tower was really intended to make dwelling in the city something that does not feel like you are losing qualities of your lifestyle. We know we have to move towards a more compact and higher quality of living instead of sprawling way, way, way out—that uses so many more resources. In this context, we had in the back of our mind how can we make [Aqua Tower] be a place that people really want to be part of and live in. The terraces are something that give you your own outdoor space, even if you are in a high-rise. The amenities and the architecture are working together to make the building be something that can draw people in, from empty nesters from the suburbs to students who want to live downtown, to live in a city and be close to the cultural amenities, to be close to work, and to reduce reliance on automobiles.