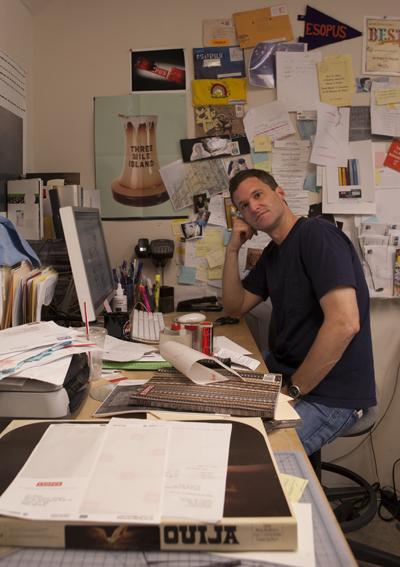

Tod Lippy

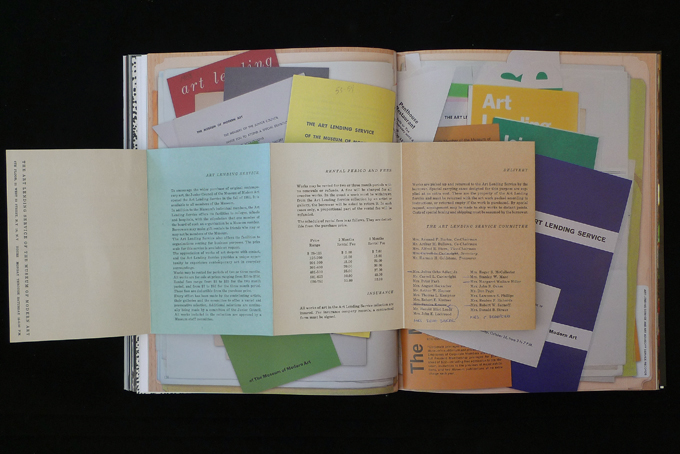

To call Esopus a magazine is a bit of a misnomer. Showcasing the broadest possible spectrum of creative endeavors, the lush, encyclopedia-thick volume is an exercise in printed ingenuity, filled with inserts, pull-outs, various types of papers and inks, a CD with original tracks, and occasionally, a do-it-yourself project. As Editor and Executive Director Tod Lippy said, “In the end, it’s less a magazine and more of an exhibition; it just happens to be on paper and in a magazine format.” Published twice a year since 2003, Esopus (pronounced, Lippy said, like “a bar of soapus”) is free from advertisements, critiques, or reviews, ideally offering a neutral, non-commercial avenue for contemporary artists to engage with the public. Lippy, who runs a one-man show as Esopus’s sole designer, editor, and manager, recently spoke with us by phone about the role inspiration plays in the magazine’s development.

The Inspiring Power of Creative Expression

I’m inspired by work that provokes me, surprises me, excites me, that seems to do something in a new way or in a different way that deepens my experience of whatever the subject matter of the piece is. I think the only reason I do anything is because I am inspired by other kinds of creative expression, and other approaches to creative expression. It’s an absolute essential part of my process to be exposed to things that are inspiring for whatever reason.

A great piece of contemporary art to me is just about as inspiring as it gets. I think art has a wonderful way to make us question our role in the world, our position in society, our beliefs. I wanted to be able to provide a context in a form for contemporary artists to bring that work to a broader audience. I also did a master’s [degree] in film, and I love particular European films and independent films that aren’t that well-distributed in the U.S. but which have had huge influences on me as a person. Fiction, poetry, basically any kind of human expression inspires me—anything that takes one person’s perspective on life and conveys it to other people. The more complex, the more nuanced the better as far as I’m concerned. It’s hard for me not to be inspired by any kind of creative expression.

There’s nothing that inspires me more than archival material. I just find it fascinating. I find it incredibly illuminating. I find it deeply personal. You go to MoMA [Museum of Modern Art in New York City], whom we do a series with, and you’ll look at letters, notes written from curators to artists, artists to curators, or whoever. You get a sense of people behind these totemic artworks or exhibitions, and how everybody had made such enormous efforts to make these things happen. That’s the way with all archives for me. I find them to be incredible documents of human expression, and the effort behind any kind of creative enterprise.

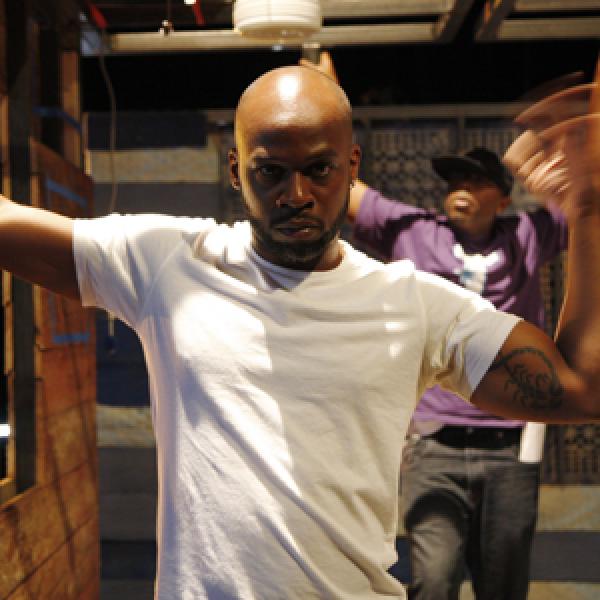

Bringing Esopus to Fruition

I set the parameters for myself as a creative person. I want to do something that’s commercial free, I want to do something that has no commercial influence whatsoever informing it. I want to do something that reaches a wide swath of people, and I want to do something with really unusual, interesting, well-known, and also emerging contributors who have something interesting to say about this or that. Inspiration is a great way to start [working on an issue]. What did I see in the past three or four months that really inspired me? It can be anything—a show at a gallery or at a museum or something on television or a film or a piece of writing. But it’s something that got me excited about art and creativity. Let’s say I happen to snag that person to do something for the issue. Then the next question is what else will be nice in the same context or in the same frame as that particular piece? That process continues until I have 12 or 13 or 15 contributions. The idea is to celebrate the individuality of each of these pieces, but also treat them in a way and organize them in a manner that makes them feel like they’re singing together, even though they’re singing different songs. There’s a commonality, not in approach necessarily but in effect, so that it doesn’t feel like a cacophony. My process is about trying to make that happen, trying to guide that in a very gentle, mostly invisible way as designer and maybe as a curator.

I think these pieces [for an issue] are so strong that for the most part, they stand on their own. I don’t think [my editorial decisions are] that special. I think it’s just that you listen carefully; look and listen and think, “What is this piece saying? How does it want to appear in the magazine? What makes the most sense for it?” Maybe it’s a vaguely mystical thing, but it is something that I find really fun, challenging, and kind of daunting sometimes. I feel like every issue is a puzzle, and every piece is a puzzle, and it will all fit together. There’s some overarching organizing principle that I may not be aware of, but it will make itself known over the course of putting together the issue. I have six months between issues, so I have a lot of time to live with these materials and think about them in a way that doesn’t involve me quickly trying to impose something visually on them that wouldn’t be there normally, or that would fight with them in some way. You spend a lot of time with an artwork or a song or anything else, and it starts to reveal itself to you.

If I have a thing in front of me—it could be somebody’s artwork or it could be somebody’s piece of music or a set of journals—then suddenly I have a way in, even if it’s a mockup of the issue that I’m working on. If I can look at it, if I can flip through it, if I can touch it, if I can manipulate it, I’m much more inspired and I feel like I have a much better handle on what to do with it than I would if I were just thinking purely out of thin air. I’m much more of a tactile person, so anything that requires a tactile response or is a material thing is very inspiring to me.

Dealing with Designer’s Block

When it's not [working], it's pretty tortuous. You want to do a good job. You've gotten these wonderful people to surrender their creative expression to you, and you want to treat it very genuinely and very carefully. You don't want to disappoint anyone. Sometimes they just fall into place, and they're ready from the minute you get something from an artist. Some artists are very particular about how they want things to appear, so there's very little for me to do in that case. But when it's something that requires a fair amount of heavy lifting on my part, it's always kind of painful until you find the format or the order that’s going to really work. It's true that there is a point where you go, “Aha! That's it.” It could be the last minute. The covers I usually do a week before we go to press. I’ll probably have nine or ten different possible covers, and I'll think, “Yeah, this is it” and then I'll go back the next day and think, “No, this is definitely not it, this isn't working.” And then almost always, magically something will pop into view, and it will be great and that's what I'll go with.

Inspiring Others

It's really important to me that this magazine gets into the hands of people who may not know anything about contemporary art, or may not know anything about poetry or may not know much about the films of Chantal Akerman or Claire Denis or Charles Burnett. I think that even if people don't become artists or don't aspire to be creative people, I think it's still nevertheless hugely inspiring to see great work or hear great work or read great work by people who are creatively inclined. My goal is to enrich people's lives and inspire them with this really extraordinary work that we've been able to feature in the magazine.

I love having [Esopus] in the hands of curators and critics and artists and writers, but to me, it's much more interesting and much more exciting to know that it's going to people who are lawyers, or maybe don't have any other exposure to the arts than the magazine. I really want to inspire people who may not be aware of the work that we're bringing to them, particularly younger people.