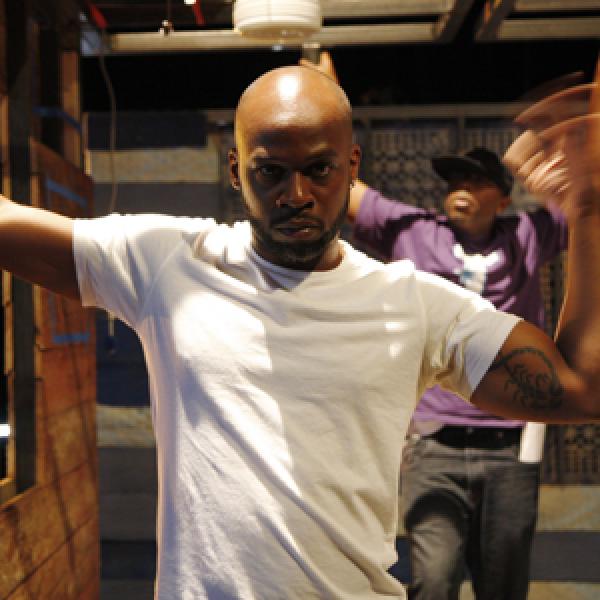

Muriel Hasbun

Photography has the ability to freeze a fleeting moment, visually fixing a particular place and time in a single, immutable frame. Photographer Muriel Hasbun, on the other hand, has managed to expand her art form in such a way that her pieces move beyond mere moments, instead encapsulating entire family histories, diasporas, and cultural movements. The chair of photography at the Corcoran College of Art and Design, Hasbun uses her work to explore her family’s unusual lineage and the tensions of her native El Salvador, often mixing historic photographs with multiple exposures to evoke the many layers of her personal story. Hasbun, a former Fulbright Scholar whose work has been exhibited around the world, recently spoke in her studio about how inspiration figures into her career.

Working Toward That “Aha!” Moment

Inspiration is something that is overrated in some ways. The whole idea that the artist all of a sudden has this amazing “Aha!” moment is obviously part of the process, but it’s not the way that work actually happens necessarily. I think that bodies of work, or some sort of insight, usually come because you’ve been toiling away for a long time, and consistently. It’s a process of figuring out what your sources are, figuring out what it is that you’re trying to say—a lot of play and a lot of work. Then somehow these things come together, and one moment you have this incredible insight into what you’re doing.

I work over time. Nothing comes quickly. It seems that my process is one where I’m collecting these different little hints that I get as I progress. Something could be brewing for a while, and so I jot it down in my journal or keep things written down and maybe I collect things in a folder or just continue thinking and all of a sudden, there’s this moment of, “Oh wow, look at that.” There’s a consistency here or there’s a thread that can pull these things together.

It’s a combination of being open, being alert to those particular things that you’re doing and that you’re paying attention to, how it is that you’re making things, and then connecting them. In that connection, something that you never imagined comes about. That’s the wonder of that particular creative moment…. When something becomes apparent to you that it actually makes sense, then that’s it. That’s the creative moment. It is such a relief. You live for those moments. But you realize that the only way that they can happen is if you’re working and thinking and you’re centered and always aware.

Why Photography Inspires

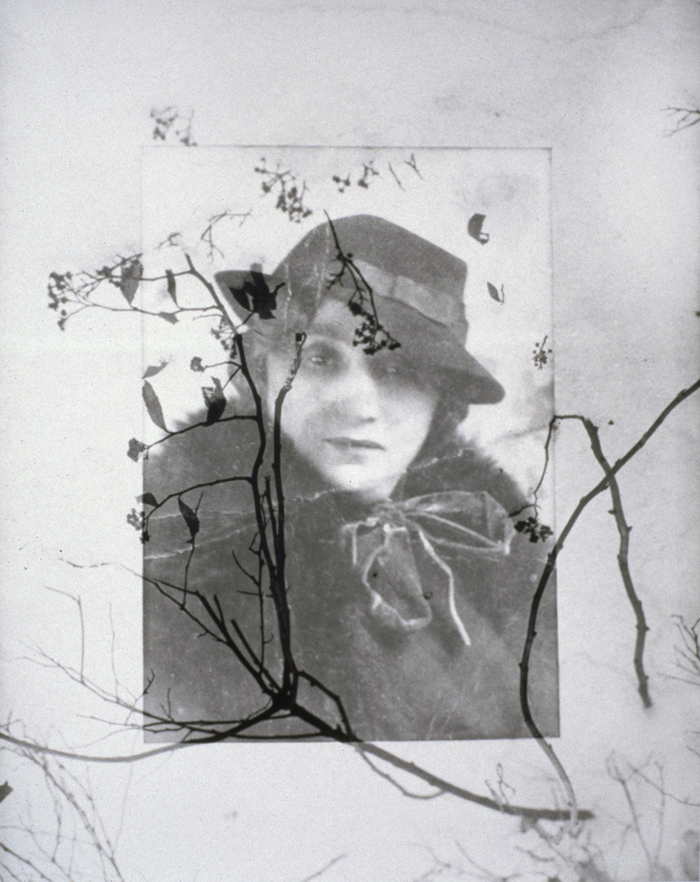

My dad was a photographer, so I learned photography through him as a teenager. At first it became a tool, because I was shy and it was a way to interact with people in high school. But photography has this incredible power of giving us an image about a particular moment. For me it serves as a document of that particular moment, but it also has this power of showing us what’s not there anymore. That, for me, is one of the most incredible things that photography can do, that it can bring us the actual light that was bouncing back from somebody’s presence. That whole idea of absence and presence is really fascinating to me, and I connect with that very intuitively. You’re exploring a world that is not necessarily the description that you see in the photograph; it could also intimate or allude to other worlds that are somehow not visible, but you could make them visible through the photograph.

The Search for Subjects That Inspire

Finding the subject of what the artwork will be is perhaps the hardest thing for an artist to figure out. It really entails getting to know oneself. In my own practice, it all began [with] trying to figure out how to say it, what visual language to use, and then what to say. I started as a documentary photographer, photographing in El Salvador during the civil war…. I found myself exploring my place through [photography.]

I came back to the U.S. to get a master’s degree in fine arts, and photography became the way that I started to think about how I could construct the place where I could live in. It became a dialogue between over there and here as well as a past and present, and also these very disparate elements that make up who I am. My background is so hybrid: I come from this family of immigrants to El Salvador, Palestinian Christian on my father’s side and Jewish French Polish on my mother’s side. All of that came to a head while I was in the U.S.: all of a sudden I was seen as Latina because I came from El Salvador. But my background was so complex that it wasn’t so simple.

So identity really became my subject…. There was this whole issue of who am I to different people, and how is it that I can reconcile what it means to be Jewish and Arab and Latina and having grown up in El Salvador and being trilingual. My work became the place where I started to experiment and answer those questions. That’s how [my photographic series] Saints and Shadows (Santos y Sombras) came about. It was really a process of finding out who I am and learning about my family and learning about my family’s different exiles and different immigration and genocide stories…. That became the territory of my investigation. It’s identity and memory and how history gets constructed and how people’s definitions of who they are become made through life. That’s what gave me this path and this incredibly rich territory to explore. I’m still investigating, and photography was a great tool to do that.

Finding New Inspiration in Familiar Territory

There are different parts of a puzzle that are being answered as I go along. When I started doing Saints and Shadows, it was kind of a coming-of-age moment where it seemed really important and necessary for my definition as a person to actually do this, to actually figure out what this was about. So it was very urgent in some ways. Doing that work, which took basically a decade, I realized that it was like putting a puzzle together. So the inspiration in some ways is always there because the puzzle’s never quite resolved, or there are other aspects of it that become apparent because I’m perhaps more ready to deal with them.

Who Do You Hope to Inspire with Your Work?

Being in Washington, DC, and being part of this greater Central-American community, I do find that there’s a certain responsibility that we have. There are two million Salvadorans in the U.S.; there are about 500,000 Salvadorans in Washington.

I think the inspiration might be to give people the opportunity for some way of expressing who they are, or a voice to express who they are or who they want to be.

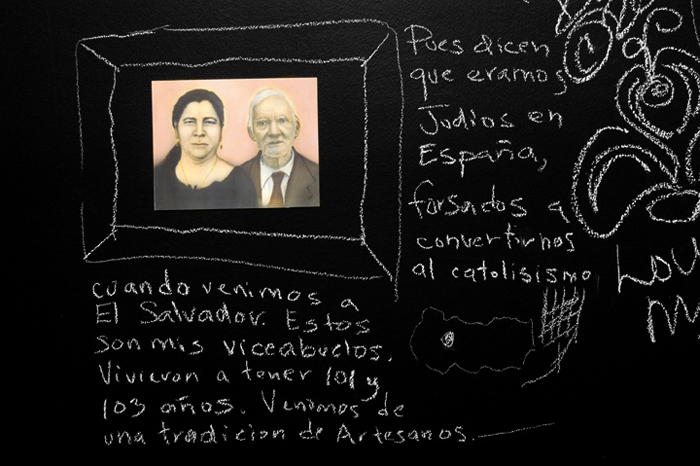

I try to…find ways of including other people who might not come into a museum, or who might not usually feel like they have something to say or have not been given the opportunity to have something to say. I figured that out with a piece that I did at the Art Museum of the Americas that was called Documented: The Community Blackboard. I had one room where I invited people to come and post their photographs and write whatever it was that they wanted to write in response to an audio piece that I had reflecting on my own story of migration. I was bringing the photographs that I had collected in El Salvador to those walls, so it was a way to have dialogue between what happened over there and what was happening here.