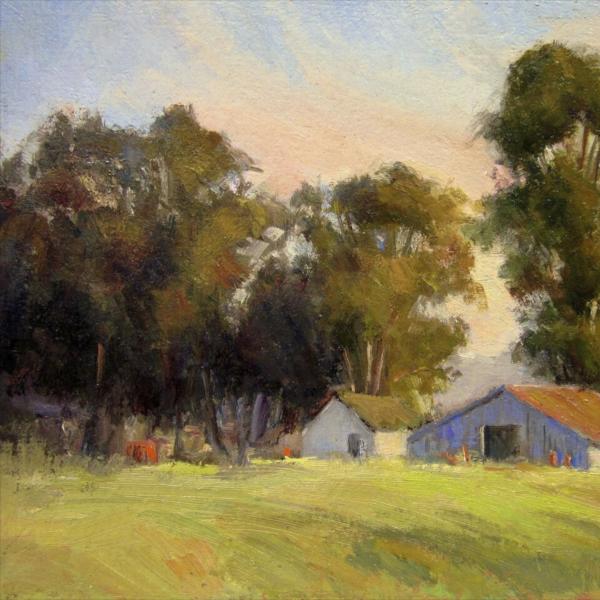

Nato Thompson: Well, the simple answer is it was a multi-artist show that existed in the north end of Central Park for a six-week period that the audience could come to and meander through the different projects and basically experience the north end, meaning the north end above the reservoir of Central Park. That’s the practical answer. The impractical answer or the dreamy answer it was an opportunity to drift in daylight. A phrase I like to use is that dreaming is best done in public. And that you get to saunter and be in your own head collectively with your fellow New Yorkers or citizens, and artists lead you on a journey that’s political, social, whimsical, morbid, fun, family-friendly.

Adam Kampe: That’s Nato Thompson, the Chief Curator for Creative Time, a seasoned arts presenting organization based in NYC. All those adjectives really do apply to

Drifting in Daylight: Art in Central Park—a NEA-supported, multimedia experience featuring nine unconventional projects that delighted audiences at the end of spring in 2015.

Like a lot of arts presenters, Creative Time didn’t work alone. In fact, that would be impossible. Acting Director, Katie Hollander.

Katie Hollander: Creative Time is all about partnerships. We don’t have a physical space. You know, it’s always been about finding locations. And in the past, I mean decades ago when there were a lot of empty lots in the city it was really just getting some sort of approval maybe from the city or maybe not. But now that there’s no vacant space within the city we really have had to adapt and think through how we partner and what those partnerships look like.

AK: And sometimes partners are unexpected.

Teri Coppersmith: My name is Teri Coppersmith, and I am the vice president of visitor experience for the Central Park Conservancy. We manage any event that comes into the park.

TC: We typically don't invite a lot of art installations into the park because it does compete with the art of the park itself. So when we do something like

Drifting in Daylight, and we agree to present an event or an art installation, it takes a lot as you can imagine to set up an art installation with different components to it. And so we work tirelessly and our operations staff really enjoyed working with the artists because they were so excited to be in Central Park.

KH: I mean it really started with the fact that we have a mutual board member Suzanne Cochran who is on the Central Park Conservancy Board and Creative Time’s board. And, of course, Central Park is one of these spaces in New York that artists always want to work within and to create a project and it’s always kind of been somewhat off limits because they have so many restrictions as to what you can do on their grounds. It’s there as a green space for the city and they do an incredible job preserving that.

KH: So in this instance it was really us talking through a lot of the projects and them understanding how the audience would engage with them, what restrictions they needed to put upon it in terms of spaces that get rented. I mean there’s a lot of space in the park that they use for graduations and weddings and filming and things like that. And so there were certain locations that just, they wouldn’t allow us to use because that was a revenue generator for them. Or favorite places in the park that really like these are places that people go regularly and they really didn’t want those to be disturbed. And they wanted people to always be able to go to their favorite spots. So we really looked to find spaces that might not be on the beaten path necessarily.

AK: Teri Coppersmith

TC: One of the reasons we did this in addition to the fact that we wanted to celebrate spring was that it was our 35th anniversary of the conservancy. And we really wanted to celebrate all of the work that we've been doing over the last 35 years. And particularly in the northern part of the park which is in a lot of people's estimation the nicest part of the park, the most beautiful part of the park and the certainly most interesting topographically. So we really were excited about an installation like this that would draw people to the northern part of the park to see something that they typically would not have seen.

Ambient up

AK: One of the nine projects featured in Drifting in Daylight was Marc Bamuthi Joseph’s stirring piece, “Black Joy in the Hour of Chaos.”

Marc Bamuthi Joseph: My name is Marc Bamuthi Joseph. “Black Joy in the Hour of Chaos” is a self-refracting second line,

Singing up, under

a 25-minute performed installation that explodes the idea or the meme of Black Lives Matter, which is often framed in terms of rage and grief, and explores the matter of the beating heart.

Music up, under

The performance is performed on a 45-foot red, black and green parachute in Central Park’s Great Hill. It involves three string players, and five poet dancers who move through theatrical meditations on “Black Joy…”

Unskinned, pinned to the post

A post race

Crossed twice, hope to die

Hope when I do there is joy on my face.

…and then invite a kind of improvisational community to join in a ritual for those who are too soon gone.

Music interlude

NT: This project was curated by myself and Cara Starke who is now the director over at the Pulitzer Foundation. And Cara is actually the one that approached Marc Bamuthi Joseph but we made all of the decisions on what artists to approach together.

MBJ: I think I was struck particularly in the moment when Cara Starke and Nato Thompson—I was struck by how this was an opportunity to consider Harlem. And so, there’s also the thing about permission. I’m from New York, but I lived in California for more than 20 years, and the kind of foundation, the undercurrent of what I wanted to make had a lot to do with signaling to Harlem that the Park was theirs as well.

Music up, under

Growing up in New York, particularly in the ‘80s and ‘90s, the northern part of the park doesn’t really interface with Harlem, not traditionally. And in fact, the Great Hill where we performed “Black Joy,” up until maybe 15 or 20 years ago was a place that you did not go, was a tent city, prostitution, illicit drug use, that kind of thing.

TC: We started restoring the northern part of the park in the early '80s with Conservatory Garden being our first project. And then we did The Dana Center, The Harlem Meer, the Great Hill in the early '90s. So we have been and continue to restore and try to preserve all of the northern part of the park so that we were serving, again, all of the communities that we serve throughout the city and way beyond.

MBJ: I think part of my artistic practice is to generate community, is to generate culture within community. Relationship, I think is at the center of how I understand the functionality of art in public space, or even in private space. So, I don’t seek to make theater, I seek to make culture. I believe that our culture is in need of healing. So, I make aesthetic medicine, and I try to make it beautiful.

TC: And that's exactly what Central Park is as well. Central Park is aesthetic medicine for the millions of people who come to it. We found that when we did a user study a number of years ago that a large percentage of the people who come into the park are only coming in to really get a respite from the sprawling urban environment around the city. They just needed to see and be part of nature.

KH: What is most rewarding is seeing the public experience it. And having those things finally come, the shows finally come together and seeing the public actually engage with the work. And there’s so much behind the scenes. But what is so special is just those moments of experience and everything with the public.

NT: In the best of cases what public art offers. Not just entertainment but an opportunity to creatively explore the world, imagine the world. It’s not about making sales. It’s not about making property values go up. Right? It’s not about these kind of indicators. It’s the big picture. It’s about dreams and exploration in the world. I think that’s what cities are built for. And I that’s what the arts should uphold. Public art in its most ambitious iteration that we feel in every project we do, matters. Because people can tell when you’re not trying to sell them something. When you’re just like hey, we’re doing this because we love the world and we’re trying to think together. And they’re like wait, “Aren’t you trying to sell me an AT&T mobile plan?” “Is there Red Bull around here somewhere?” You’re like, “no!” We genuinely, like a public library, come out of a spirit of great civic behavior.

TC: The original designers of the park Olmstead and Vaux actually designed the park for people to meander through it. And that was intentional. What they did was they designed it so that you would come upon a landscape and see another landscape or another vista across the way. And you would make your way to that. You would meander to that next vista. So

Drifting in Daylight exhibition really fit very nicely in the original intent of how you were supposed to experience the park.

CREDITS – That was Teri Coppersmith, director of visitor experience at the Central Park Conservancy, along with chief curator and executive director of Creative Time, Nato Thompson and Katie Hollander, and last but not least, artist Marc Bamuthi Joseph on the unique partnership that enabled Drifting in Daylight: Art in Central Park to come to life. Thanks to everyone who contributed. For more on unexpected partnerships, check out the rest of NEA Art’s latest issue. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I’m Adam Kampe.

Music: