Transforming Journeys

If you think that the arts in New York City only come to life within the rarefied atmospheres of Carnegie Hall, Broadway theaters, or the Metropolitan Museum of Art—think again. In a city revered for its widespread creativity, even grabbing the nearest subway train or bus can become an experience elevated by art. Case in point: the Poetry in Motion initiative, sponsored by the Metropolitan Transit Authority and Poetry Society of America and supported by the National Endowment for the Arts.

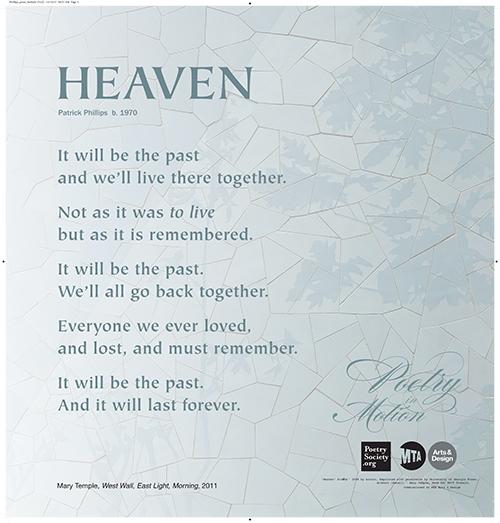

“It will be the past / and we’ll live there together,” begins one particularly striking poem, beautifully printed atop a backdrop of leaves and stone-like fragments and recently posted in hundreds of train cars and buses across the New York transit system. “Not as it was to live / but as it is remembered. / It will be the past. / We'll all go back together. Everyone we ever loved, / and lost, and must remember. / It will be the past. / And it will last forever.”

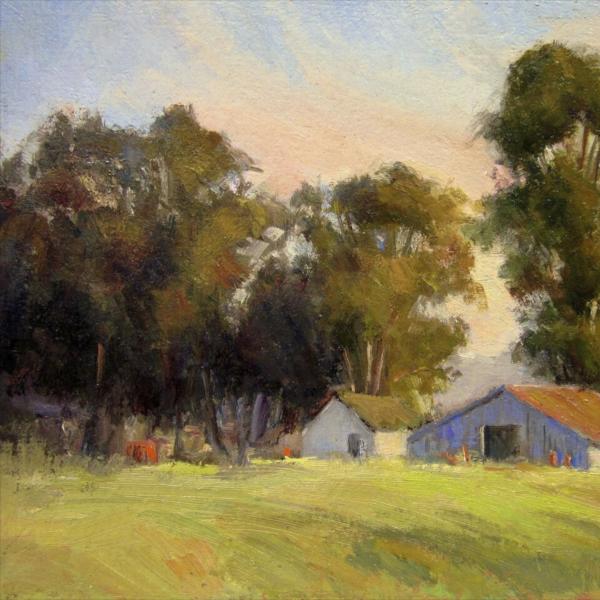

Those evocative words come from the poem “Heaven,” written by Patrick Phillips. It is among more than 200 poems that have been shared with subway riders, bus passengers, and rail commuters since Poetry in Motion’s inception in 1992. As with “Heaven,” each work is coupled with museum-quality visual artwork, reproduced on large posters, and posted publicly to reach more then seven million customers every day.

The goal is a simple one. “We are bringing poetry to the daily experience of our customers,” said the Metropolitan Transportation Authority’s Sandra Bloodworth. “We want them to know that an agency cares enough to bring the arts to their journey.”

Poetry in Motion began when Elise Paschen, the then-executive director of the New York-based Poetry Society of America (PSA), visited London on a reading tour and spotted a poem by English poet Michael Drayton displayed publicly on the Tube, London’s own subway system. Inspired, she began to wonder if publicly placed poetry could elicit a similarly striking effect in the U.S. “We aim to share poetry that is powerful and meaningful,” she said, “hopefully bringing a thought to ponder, or a smile that our customers might not have otherwise experienced.”Bloodworth serves as director of the MTA’s Arts and Design program, the arts arm of the agency, launched in 1985 in conjunction with a major reconstruction of the New York City transit system. Today, nearly 2.6 billion people traverse the city on MTA trains every year, their journeys augmented by the site-specific, permanent installations created by more than 300 artists, all commissioned through the program that Bloodworth currently leads. Though Poetry in Motion is just one initiative that she oversees, it is amongst the most visible—and widely loved—that the city has to offer.

Simultaneously, the then-president of New York City Transit, Alan F. Kiepper, was also visiting London and became similarly impressed with the display of word-based art. “It was a case of synchronicity and serendipity,” said Alice Quinn, who currently leads the PSA. “When Alan returned to the U.S., he poked around and landed on our organization as a place to phone. He and Elise put their heads together and launched this program. Immediately, it became immensely popular.”

The buzz surrounding New York’s creation of Poetry in Motion quickly inspired similar installations in the public transit systems of Chicago, Atlanta, Baltimore, Boston, and Houston, as well as Washington, DC. Years later, recession economics halted some of those programs, as transit authorities chose to use the space occupied by the poems to generate much-needed advertising revenue.

But the poetry initiatives proved resilient. Poetry in Motion itself returned in 2012 after a few-year hiatus, and similar programs in Los Angeles, Portland, and Nashville continue to thrive. In Nashville, for example, local students and songwriters continue to be commissioned to craft poems displayed for public enrichment.

|

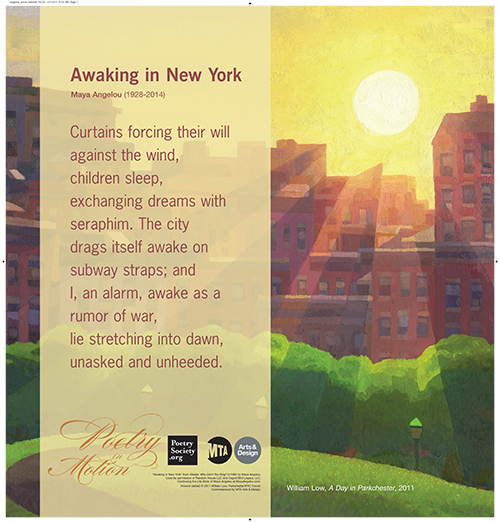

In New York City’s current iteration, Poetry in Motion introduces two poems quarterly, up to eight total each year, with newer poems gradually phasing out older ones. The first poem to be displayed in 1992 was an excerpt of Walt Whitman’s “Crossing Brooklyn Ferry”; more recent installations feature works from poets as widespread as Maya Angelou, Jeffrey Yang, Vera Pavlova, and Lao Tzu. The process of choosing poems begins with the PSA, which pre-selects packets of roughly 15 to 40 works and offers them to the MTA for review. Bloodworth and her colleagues make the final selections, pair the poems with artwork, and post them in train cars across the five boroughs.

When initially gathering poems, Quinn looks for works that can easily be experienced in between stops, but also ones with staying power. “It must be a poem that can be re-read endlessly with delight and feeling,” she said. “It can’t be something that will be spent for you if you’ve seen it once or twice.” The PSA also seeks out diversity in its choices, picking works from poets of dramatically different ages, voices, and backgrounds.

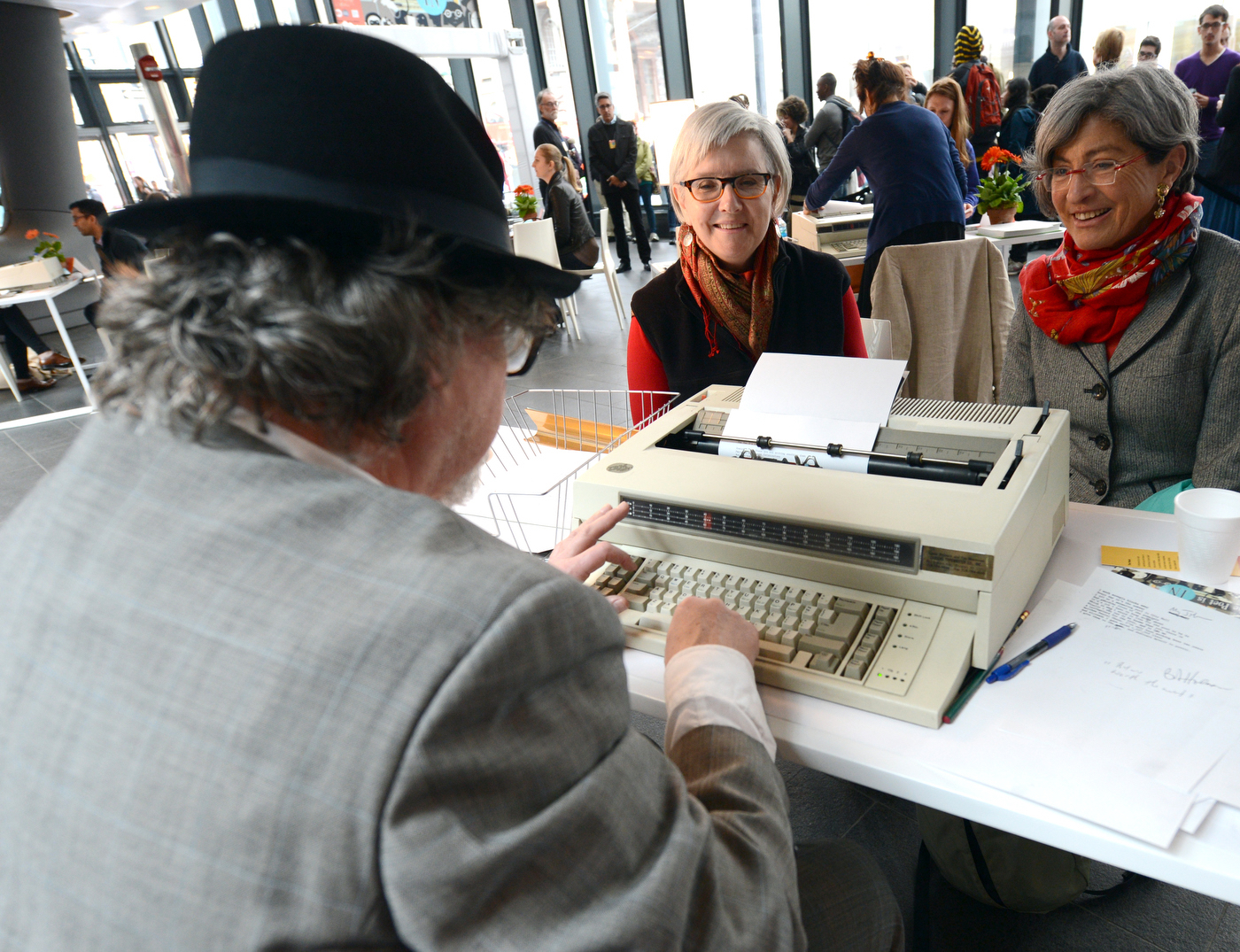

The collaboration between the MTA and PSA extends beyond the subway car as well, and the PSA co-presents readings in honor of Poetry in Motion poems and installations. In 2014, thousands attended two days of poetry-related festivities at Grand Central Terminal, where Poetry in Motion works were projected on the walls of Vanderbilt Hall and acclaimed poets occupied old-fashioned desks, working on typewriters under green library lamps to craft individually customized poems for the attending public.

In 2015, the MTA and PSA also hosted a similar program called Poetry in Motion: The Poet Is In at the MTA’s new Fulton Center transit hub. For the program, poets were paired with customers and composed poetry for them on the spot. “The concept was inspired by the Peanuts character Lucy Van Pelt’s advice booth,” said Bloodworth. Though it may not be as obvious as with music and film, poetry is a tremendously popular art form, affirmed Quinn. “As we know from memorials and weddings, when we want to celebrate, we reach for a poem,” she said. “So putting poetry out there, where subway riders can have a surprise encounter with it, serves as homecoming for many, a rendezvous with an art form that, at some point, they treasured and are thrilled to return to.”

|

Quinn recalled watching a woman become engrossed in the Poetry in Motion poem “Wilderness,” by Lorine Niedecker, during a trip on the 1 train from 14th Street to 96th Street. “People often memorize the poems, which is so gratifying,” she said. “This woman was reading it over and over and obviously trying to get it by heart. I was so moved, because it's a very hard-hitting poem.”

For Bloodworth, Poetry in Motion is about more than distracting subway-goers from their commutes. “Introducing quality art tells the public that we are dedicated to providing a meaningful journey,” she said. “From the beginning of the Arts and Design program in 1985, we immediately saw the reaction of the public experiencing art introduced into the transit environment—and the difference it made in proclaiming that these spaces are important, our customers travel here, and we want it to be a good ride!”

It’s clear that poetry has power, she continued, a unique ability to transform people’s journeys. “Art, poetry, and music are not a panacea, but they are powerful in bringing a quality experience to a century-old subway system,” she said. “I see the program continuing into the future, bringing poetry to millions of people every day.”

The fact that poetry—as well as art and music—exist within the New York subway is a worthy end unto itself, continued Bloodworth. “No one has to explain to a New Yorker why the arts are important in our lives and to our city,” she said. “They know. And that’s probably the thing I love the most about living in New York.”