Empowering through Art

Artist Marisa Morán Jahn leads participants in co-choreographing a dance while learning about the growing movement for domestic workers’ rights at a Domestic Worker Disco workshop during the Allied Media Conference in Detroit. Photo by Marisa Morán Jahn

While many of us may take benefits like eight-hour workdays, protection against workplace sexual harassment, and workers compensation insurance for granted, these benefits didn’t exist until the passage of fair labor laws in the 1930s. While the National Labor Relations Act and the Federal Fair Labor Standards Act improved things radically for many workers, domestic workers were purposefully excluded from the law’s protections because most of those workers were African American. Today, domestic workers—nannies, housekeepers, and home care aides among them—are still fighting for basic workplace protections. That’s where artist Marisa Morán Jahn and labor activist Natalicia Tracy come in.

Jahn is the executive director of Studio REV-, a New York-based nonprofit dedicated to transforming the lives of low-wage workers, immigrants, and women through creative media. She began her work with domestic worker issues in 2010 after New York State passed its Domestic Worker Bill of Rights, the first ever in the United States. Domestic Workers United, an NYC-based group and organizing member of the National Domestic Workers Alliance (NDWA), asked for her help in getting the word out about the new law. For Jahn, “getting the word out” involved not only spreading information about the new rights of domestic workers but also empowering the workers to see themselves as a community that could take the fight into their own hands. According to the NDWA, 95 percent of domestic workers today are women and 46 percent are immigrants—two groups that have historically been marginalized and disenfranchised.

|

“To me the arts are particularly useful for building a movement, building a sense of cohesiveness, and empowering a group of people who may not have thought of themselves as a group before,” said Jahn.

She developed several platforms for spreading that message. One of the first ideas was to develop a mobile app, the Domestic Worker App, that could connect users to a call-in radio show that broadcast humorous, educational vignettes about the types of situations domestic workers regularly run into. Jahn described the programming as “Click and Clack for nannies,” referring to the former hosts of NPR’s popular Car Talk radio program. It was important to Jahn that the program be accessible by any basic cell phone—not just smartphones—so that the workers—many of whom work 60-hour weeks in addition to caring for their own households—could access the show whenever they had free time.

It was also critical that the radio broadcast feature actual workers’ stories using actual workers’ voices. As Jahn explained, “[Domestic workers] feel invisible and creating artwork around [their work] dignifies the labor that domestic workers do.” To collect the stories and promote the project, Jahn designed the NannyVan, a brightly colored van and sound studio that she drove across the U.S., stopping at places such as workers’ centers, parks, and other places where domestic workers and employees might gather. According to Jahn, news of the app spread by word-of-mouth even before she did any official advertising, and the app now gets as many as 1,200 calls each month.

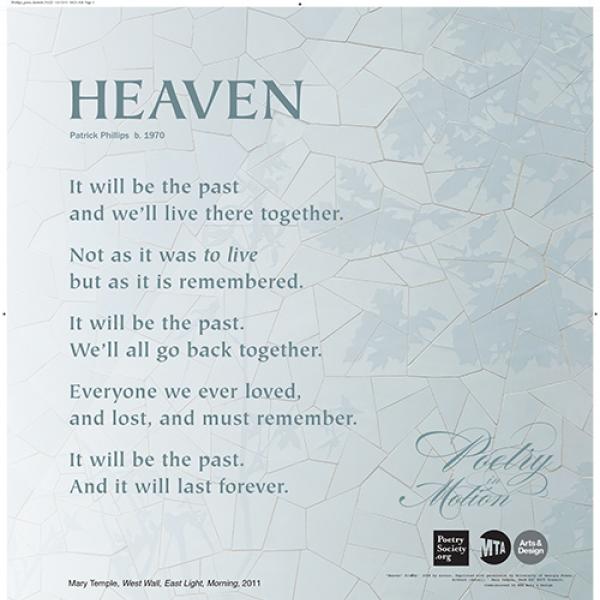

Jahn also designed palm-sized cards about the Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights that participants could share with their peers as well as poster-sized artworks that could be displayed throughout the community at both workers’ spaces and cultural spaces such as museums.

|

In New York City, Jahn also worked with participants of a dance exercise class targeted to domestic workers. Working with class leaders, Jahn transformed the class into an organizing tool by incorporating gestures reminiscent of the workers’ daily tasks, such as mopping and ironing. According to Jahn, the dance fulfilled several roles in addition to providing exercise to those in a physically demanding job. “It’s a communication piece and a way for them to feel as if they can talk about being part of a larger movement they may not have known they had been part of. It’s also a way for them to empower themselves in their bodies or through their bodies.” The group also performed in public, which Jahn said was “a really lively way for the public to get involved and understand what’s happening.”

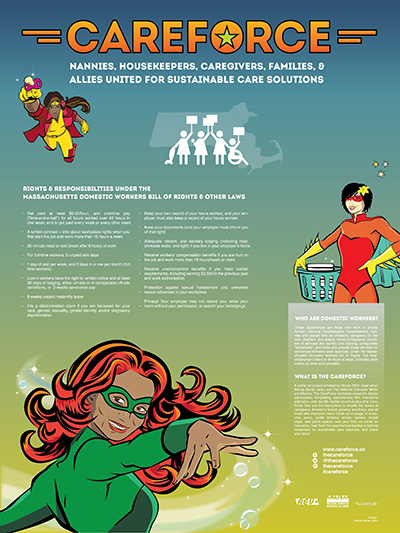

In 2013, Jahn joined forces with Natalicia Tracy, executive director of the Brazilian Worker Center. Based in Boston, Massachusetts, the center—a recent NEA grantee and an affiliate of the NDWA—is active in domestic workers’ advocacy, education, and leadership training, among other areas. Tracy asked Jahn to work with the center and its partners on an ongoing project to create tools with a health and safety emphasis. As Jahn explained, “Domestic workers have not been traditionally covered under OSHA [Occupational Safety and Health Administration] laws… they face a disproportionate amount of health injuries, workplace injuries, more than, for example, someone who is a receptionist who is covered by the [existing] labor law.” The partners developed posters, games, comic books, and dance movements to help inform the workers of potential hazards and how to mitigate them.

Before partnering with Jahn, Tracy and her team had already seen the powerful effects of injecting the arts into their work. For example, the center frequently holds focus groups to make sure its advocacy work matched the needs of its constituents. They employ theater exercises, drawing projects, and even singing in order to draw out the workers and make the meeting spaces more engaging. “When you come to those spaces for meetings, even to learn about your rights, you want to bring some creativity into those spaces because that might be the only fun that person’s going to have for the whole month,” said Tracy.

The center had also created a traveling exhibit of black-and-white photos of female domestic workers, which has been exhibited in locations such as college campuses, bank lobbies, and libraries. The exhibit allowed workers who often feel invisible to be seen and created a safe zone in public spaces to talk about the stories of the women captured in the photographs and the issues they face as nannies and housekeepers. As Tracy explained, “The idea is to show them as human beings, to really humanize the issue. What I’ve seen is how people open up in those spaces. It opens opportunity for talking and to share stories and to talk about people as just being human beings.”

Having already experienced the power of the NannyVan, Tracy was eager to adopt many of the arts tactics employed in New York to mobilize Massachusetts workers around the state’s newly passed Domestic Workers’ Bill of Rights as well as to advocate for a similar law in Connecticut, where the Brazilian center has a branch. The project, which recently received NEA funding, is now known as the CareForce and comprises a superhero poster series celebrating domestic workers and a Domestic Worker Disco, which the partners describe as “stroller figure eights and mop waltzes that encode ergonomic info while promoting workers’ health and safety, weaving together their stories, and making visible the labor of domestic work that’s often rendered invisible.”

|

|

The CareForce project also includes a new and improved version of the NannyVan—CareForce One—which uses augmented reality technology to encourage participants to listen to stories of fellow caregivers as well as to tell their own. To turn on the system, the user points a smartphone at the vehicle, which then triggers a 40-second report called “the superhero report.” Each short audio burst will demonstrate the importance of the work caregivers and other domestic workers do. Jahn cited one superhero story in which a caregiver coaxed an Alzheimer’s patient who had stopped speaking back to speech through dedicated attention and conversation. After listening, workers are encouraged to share their own “superhero” stories in audio or video form.

The project team is also working with Oscar-winning filmmaker Yael Melamede to create digital shorts from the footage gathered as CareForce One tours the country.

While Tracy and Jahn agree that getting legislation on the books to give domestic workers access to the same rights and benefits as other workers in the U.S. is an important goal, they also stress that the way in which the arts transform the conversation to empower each individual worker is some pretty powerful stuff. Jahn described that power as, “Hundreds of people who say to us, ‘You know, I never identified as someone who had any rights…. I now think about myself differently.'”