The Idea or the Physicality?

On a recent morning at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, DC, Chief Conservator Gwynne Ryan was overseeing the de-installation of Alexander Calder’s Two Discs (1965) in the museum’s outdoor plaza. Wearing a hard hat and reflective vest, and monitoring a crane and crew of riggers, Ryan looked more like a construction foreman than a conservator. But considering other pieces have required her to learn how to preserve soap, chocolate, a floor made of beeswax, and to learn about the mating process of snails, perhaps a turn as a foreman is one of the less challenging roles Ryan has had to play. As Ryan put it, when it comes to conserving contemporary art, “You don’t get bored.”

In the past century or so, artists have increasingly moved beyond the canvas, exploring natural materials, industrial materials, and daily ephemera—none of which were necessarily designed with durability in mind. While this has expanded our collective notion of what art can be, it presents a continuous challenge for conservators, and calls into question what, exactly, should be preserved.

“Sometimes there are conceptual aspects or immaterial considerations that might supersede that of the material,” said Ryan. For instance, what was the artistic intent? What is the artwork’s lifecycle? What is more appropriate: rehabilitation of a piece to preserve the original, or replication, so that its overall aesthetic and meaning can be better maintained?

To address these complexities, artist interviews have become increasingly popular within contemporary art conservation. Carol Mancusi-Ungaro, Melva Bucksbaum Associate Director for Conservation and Research at the Whitney Museum of American Art, is a pioneer in artist documentation and began the Artist Documentation Program at Houston’s Menil Collection in 1990. Described as “living wills” in a recent New Yorker article, these interviews allow conservators to document the process, approach, and intent behind the piece, and help them

determine the most appropriate way to conserve the artwork moving forward. “It’s really key to work with the artist and understand what one is preserving,” she said. “Is it the idea or the physicality?”

|

Throughout the conservation process, every decision, action, and notable conversation is documented. This will hopefully prevent future conservators from having to guess what was original and what was the work of restorers, and why any changes were made. “There are huge records of what is done, and the thinking behind what is done,” said Mancusi-Ungaro. “With modern art, you have the responsibility of being the first hands on [to conserve a piece]. So you’re much more cautious with that.”

Rather than wait until a piece suffers damage, the work of conserving contemporary art begins at acquisition. The challenge, Ryan said, is to map out how to preserve a piece 50, 100, 500 years down the road when the artwork itself is still in its infancy. “Sometimes the artist is still making [a piece], and figuring out what it is they’re even making,” she said. “For us to be trying to understand what it is going to mean to own this, or what elements can degrade, what elements can be replaced—I find it fascinating. Even when an artwork is coming into the collection, it is still becoming.”

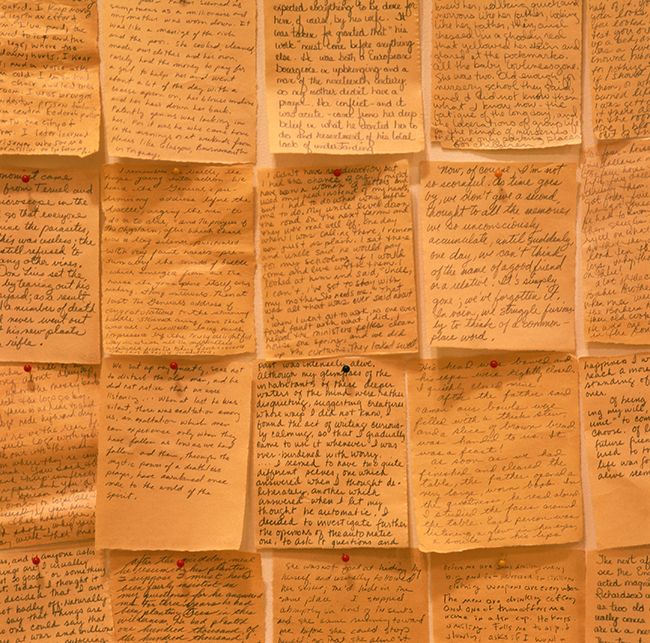

Sometimes, she said, conversations with an artist lead to an approach that “we absolutely never would have thought of on our own,” and might even be considered improper had it not been personally sanctioned by the artist. For instance, the Hirshhorn acquired in 2004 the room-sized installation palimpsest (1989) by Ann Hamilton, a 1993 NEA Visual Arts Fellow and 2014 National Medal of Arts recipient. A meditation on the loss and preservation of memory, the work consists of floor tiles hand-cast from beeswax, and walls pinned with squares of aged newsprint scrawled with handwritten memories, which flutter in the breeze of an oscillating fan. In the center of the room is a vitrine full of snails munching on heads of cabbage.

“Almost all of the components are utilized in a way that is not going to help their preservation,” Ryan laughed. Nor were they necessarily meant to be preserved. In a recent interview, Hamilton noted that the newsprint was meant to disappear with time, and the snails, obviously, had a shelf life. “When a piece is saved, and it needs to be stabilized, what problems does the intention of ultimate disappearance come to have?” Hamilton mused. “How is work that’s about change and without firm edges considered within a museum collection? Those are things I’m still trying to figure out.”

After a series of conversations between Ryan and Hamilton, the Hirshhorn ultimately decided to host a multigenerational workshop for docents and teens where they wrote their own fragments of memories on news- print squares. These will then be used to replace the original newsprint once it becomes too brittle or faded to display. It was an unconventional approach to conservation that both Hamilton and Ryan feel will keep the piece alive, rather than “freezing it in time and treating those elements as if they’re precious,” said Ryan.

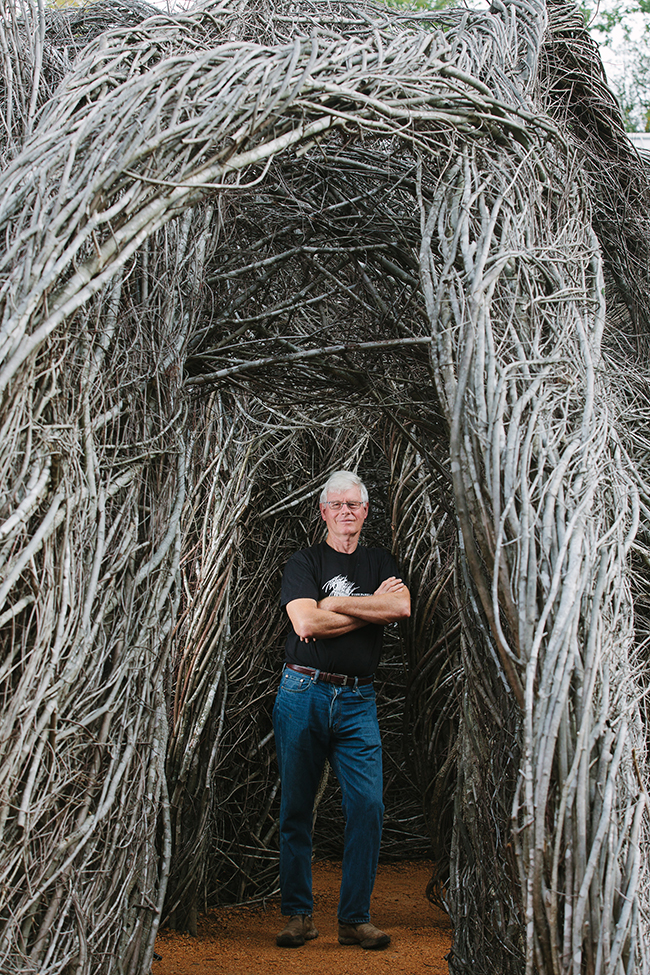

It’s a sentiment artist Patrick Dougherty shares. Dougherty, who received an NEA Visual Arts Fellowship in 1990, constructs large-scale, architectural installations made entirely of found sticks, which look at once entirely fantastical and somewhat primitive. The works aren’t designed with posterity in mind, and typically degrade within two or three years. For Dougherty, this impermanence “turns the attention of an artwork back to what I think it should be—not something that’s permanent or that you can buy and sell and gain a return on your investment. It refocuses on the ‘now’ experience of looking at a work and just being compelled by it.”

While it’s an idea that might trouble art historians, Dougherty isn’t concerned about the future. The associations that people have with sticks, which often stem from childhood or the natural world, are what make his sculptures resonate, and he isn’t certain the emotional impact would be the same—today or for future generations—if the same sculptures were made from different, more durable materials. Because his works are almost exclusively outdoors, and seen by thousands of intentional visitors and happenstance passersby, Dougherty reasons that the emotional impact of his work is compressed “into a few weeks” instead of what would take centuries in a museum.

|

Currently however, he does have two museum works on view, one at the North Carolina Museum of Art and the second at the Renwick Gallery in Washington, DC. The latter, titled Shindig and made of willow branches, was commissioned by the Renwick as part of its exhibition

WONDER, which celebrated the museum’s reopening after a two-year renovation. Dougherty said the Renwick is choosing not to keep and conserve the piece long-term, partly due to concerns over beetle infestations and fire dangers. It’s an issue that illuminates not just the vulnerability of certain unconventional materials, but their potential effect on other pieces in a collection.

And yet, we live in an age where even ephemeral work will likely endure far longer than was once possible, at least in some form. “I think many of the materials that we see as being ‘unconventional’ probably have been art-making materials for a lot of people through the generations,” Ryan said. “We just don’t have it around to see.” But with camera photos, blogs, videos, and criticism all online, temporary work has been given seemingly infinite ways to live on. Since WONDER opened in November, the Renwick had been tagged approximately 60,000 times on Instagram, giving the nine larger-than-life works on display—Dougherty’s included—a way to survive digitally if not physically.

And perhaps one day that is how all artwork will survive. Despite the artist’s wishes, a conservator’s efforts, the documentation process, or a museum board’s concerns, “Things have a life,” said Ryan. “As much as we want to try and keep everything in perfect condition as long as we can, ultimately chemistry takes over and physics happens.”

Dougherty agrees. As he put it, “I’ve always thought that everybody does temporary work.”