Traversing the Wasteland

Former Federal Communications Commission Chairman Newton N. Minow once called television a “vast wasteland” (which was the equivalent to “Hey you kids, get off my lawn!” to those of us who rushed home after school to see Gilligan’s Island reruns in the 1970s), but in the past 15 or so years, it has been anything but. First, the premium cable channels began producing high-quality programming that bypassed the limitations of the traditional four television networks. As scripted dramatic series like The Sopranos, The Wire, and Deadwood began getting critical (and popular) acclaim, basic cable channels like FX and AMC began making their own original material, such as The Shield, Mad Men, and Breaking Bad.

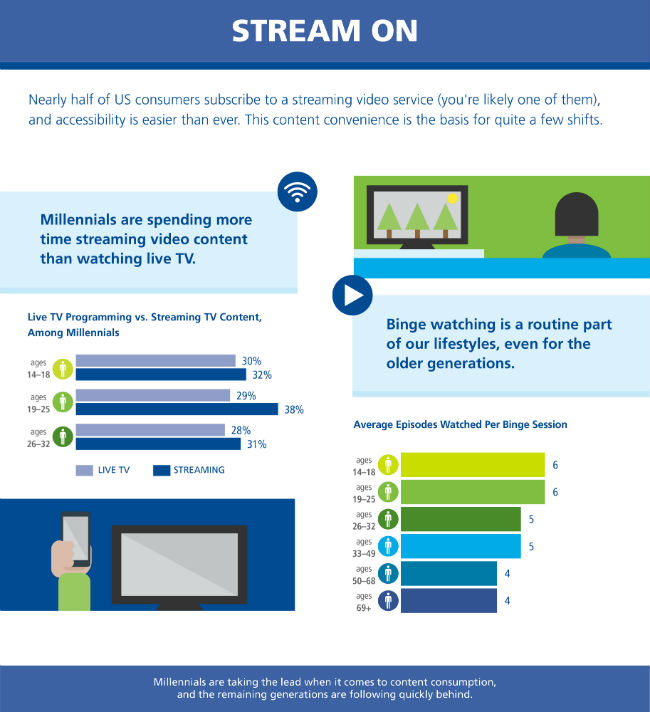

It was just a matter of time before the streaming companies got into the action. Arguably, television has been one of most impacted art forms over the last ten years by the proliferation of streaming options. Companies that were once depositories of old movies suddenly were creating new content, mostly in the television mode of half-hour to hour-long series. And they were using a new format for distributing them. Instead of dropping an episode every week, they made an entire season available all at once, creating a new phenomenon: binge-watching. According to Deloitte’s Digital Democracy Survey, 10th edition (March 2016), 70 percent of U.S. consumers watch an average of five episodes at a time, with 31 percent binge-watching on a weekly basis.

The combination of higher quality and quantity of programming coincided with the expansion of the Internet. Since the beginning of the millennium, Internet users have risen from roughly 400 million to more than 3.3 billion estimated for 2016 (perusing more than one billion websites). As the Internet became more and more ubiquitous in daily life, more people took to sharing their opinions on the television shows they were watching (and pretty much everything else) through websites, blogs, social media, e-mail, and texting.

With so many shows out there and so many opinions, how does one know what is good? In the arts, that’s usually where critics come in. They can provide a pathway to understanding what is good and what is not, and why, with their opinions rooted in deep knowledge of an art form’s history. But with the Internet, ordinary people gained a platform for their own opinions, and became part of the discussion about what makes a television show good or not. It has led to an overhaul of traditional television criticism, starting with a mass migration from traditional media to online publications.

Being an online critic requires a different mindset from the traditional newspaper critics. “When you’re writing for the paper, you’re writing for the sort of mythical general audience,” said Alan Sepinwall, author of The Revolution Was Televised and television critic for Newark’s Star Ledger for 14 years before starting his own blog What’s Alan Watching? “You’re writing for the person who maybe doesn’t know the show. And you really need to explain everything to them.” Online, however, the audience is different. The people who are searching out the blogs and e-zine reviews already know the shows, “so I can dive into it more deeply than I would’ve been able to at the paper,” Sepinwall said.

“I feel like I get the fans, I understand where they are coming from,” said Sonia Saraiya, the e-zine Salon’s television critic from 2014 to 2016 and now a critic for Variety. “There’s so much passion in that community that translates to actual business decisions. I feel like I’m in conversation with the people who make TV, the people who watch TV casually, and the fans. For example, when I used to write about Downton Abbey, I would sometimes have a sense that as I was writing a paragraph, ‘I think the fandom’s going to like this one.’ Then sometimes you’d see the paragraph taken out and quoted on different fan sites. To me that’s awesome, because that’s the conversation.”

With all the material out there, it’s a matter of picking which conversations you want to have. Joel Waldfogel, an economics professor at the University of Minnesota, found that the number of new shows premiering has gone up from roughly 25 in the 1960s to more than 200 per year since 2010. Certainly too many for a critic to watch on a daily basis, write about, and still have time to, say, eat and sleep. So they have to pick and choose, and determine what works best for their audiences. Eric Deggans, who started as NPR’s first full-time television critic in 2013 after nearly 20 years at the Tampa Bay News, noted, “NPR is all about choosing shots wisely. We don’t try and cover the waterfront. The idea is to figure out interesting stories that we can dig into and that the NPR audience would be interested in, or potentially would be interested in.”

|

The plethora of content from various television outlets, however, offers an environment where shows that might not have made it through the traditional gatekeepers can get made. “A show like Transparent would never have existed five years ago,” Sepinwall said. “A show like Orange is the New Black, with such a diverse cast of women across different races and sexual orientations and gender identities—that never would’ve happened. When you look at some of those ABC comedies, like Black-ish or Fresh Off the Boat, even in a very traditional format like family sitcom, if you do something as simple as tell a story about a slightly different family, all these clichés that have become so tired suddenly become new. It becomes a show that even if you’re not Black or Asian American you’re going to enjoy and watch. So it starts to make good business sense.”

This has led to online conversations becoming more diverse as well. Saraiya suggested that conversations have become more elevated on the Internet and “lead in directions that we haven’t had before. For example, on The 100 on the CW, one of their lesbian characters that they had just introduced was killed off by a stray bullet by the one openly homophobic character. This was a show that had really reached out to its fans and was proud of its inclusivity, and the fact that this character got killed led to what I thought was a very interesting fan-driven and critic-participation conversation about what kind of characters get killed and why they get killed.”

Television’s reputation since the beginning of the millennium has risen because, well, it has gotten better. That has created a stronger, more dedicated fan base that now has the Internet at their disposal. “What I think is happening,” said Deggans, “is that it changes what kind of conversation the public wants to have about a show— which will change how I cover that and how a lot of TV critics cover it.”

The fact that you can watch TV whenever and wherever you want nowadays, and if you are willing to pay, can choose whatever you want to watch as well, makes viewers more invested. While, according to previous Deloitte surveys, only 11 percent of consumers owned a smartphone in 2006 and just 15 percent watched television from the Internet in 2007, nearly half of all U.S. consumers now subscribe to a streaming video service, with more than half watching movies and TV shows via streaming on at least a monthly basis.

Now that the traditional networks are getting into the streaming game, with NBC launching Seeso with original content and the other networks discussing the same to reach more viewers opting out of the old distribution model, maybe television is not the vast wasteland it was one purported to be. Vast? Certainly. Wasteland? Not so much.

“TV is as good as it has ever been, and for the last 15 or so years, really extraordinary,” Sepinall said. “And it’s become sort of hard to ignore at this point. When I started out and people would say, ‘What are you doing?’ I’d say, ‘I’m a TV critic.’ They’d, a) be surprised that was a job, and b) feel sorry for me that I had to watch so much TV. Nowadays, as soon as I mention [I am a TV critic] all they want to do is talk about their favorite show.”