On (Not) Measuring Arts and Culture

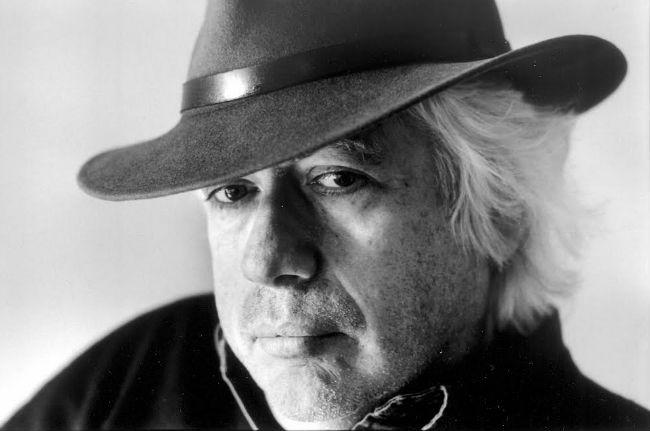

"Aesthetics is the mother of ethics," wrote Russian-American poet and Nobel laureate Joseph Brodsky. The slogan is hard to dismiss when confronting the speech and writings of Leon Wieseltier, currently Isaiah Berlin Senior Fellow of Culture and Policy at the Brookings Institution. Prior to landing there, he reigned for more than 30 years as literary editor of The New Republic. Also known for his book-length meditation Kaddish—the fruit of a journal he kept while mourning his father’s death—Wieseltier has been fearless, as writer and editor, in making moral and ethical statements in the form of literary essays, book reviews, and cultural commentary. On January 7, 2015, Wieseltier published an essay, “Among the Disrupted,” in The New York Times’ Sunday Book Review. His essay complained that “the discussion of culture is being steadily absorbed into the discussion of business.” The essay faulted the “overwhelming influence” of quantification and “the idolatry of data.” For the rest of the month, reader reactions thronged the review’s “Letters” section, and more than 3,200 Twitter users had responded to the piece by the end of the month. But how would Wieseltier regard the enterprise of conducting social sciences-based research into the arts? Do his criticisms afford leeway for organizations tasked with bringing empirical data to bear on cultural policy and practice? More than a year later, Sunil Iyengar, NEA director of Research & Analysis, resolved to ask him.

SUNIL IYENGAR: When I first read your article, I thought, “Here you’ve hurled a big challenge to all of us who toil in the field of measuring culture, to those of us who seek to quantify culture to justify policy decisions.”

LEON WIESELTIER: I hope so! We use all kinds of phrases and words that, if you look at them for a minute—at least when I look at them for a minute—I find grotesque. For example, to refer to the potential of individuals to create and produce as “human capital”—there’s something wrong with that. It regards human capabilities from the standpoint of owners and managers.

There is a great deal that numbers cannot capture, if one is interested in the tones and textures of things, which sometimes are what is most important about a particular subject or discussion. Numbers give people a sense of certainty, which in certain realms is specious. People like to believe they have attained clarity, but there are realms where a mathematical kind of clarity is not possible.

We all live in many realms. Each of these realms has a temper and temporality of its own. Whereas importing categories from one realm to another may say something interesting—it can be enlightening to see the cultural dimensions of a political phenomenon, or the economic dimensions of a cultural phenomenon—the fact is that most often the importation of categories from one realm into another is a kind of imperialism.

The realms can shed light on each other. What they cannot and should not do is conquer and occupy and colonize and control each other.

The field that practices this imperialism most regularly and most successfully is economics, which our country believes is a source of life wisdom. We now live in a society in which our authorities on the subject of happiness are economists. By my humble lights, there is almost no subject imaginable that is less a subject for economists than happiness.

|

IYENGAR: To measure the value of arts and culture in society: is this a fool’s errand, then, or do you think there are probably legitimate ways within the social sciences?

WIESELTIER: I think the question of what the value of art is in society is not a scientific question. By the way, I think that the question of what the value of science is in society is not a scientific question either. Science cannot tell us what the place of science in our lives should be. That’s a philosophical question. Philosophy is even grander and greater than science. Similarly, the question of what the arts mean in a society, what place they should have in our lives, is not a question for science to answer. It’s a category mistake. It’s another misapplication of the terms of one field aggressively against another field.

IYENGAR: But in a policy arena, where one constantly has to justify public spending, for example, or build public will for these kinds of initiatives, whether in the arts or humanities—without relying on performance measures or evidence, how would we do that?

WIESELTIER: There are many, many realms of social policy in which numbers are entirely appropriate. When you aggregate individuals, and make generalizations about them, for the sake of understanding certain social behaviors, it may not be germane to wonder about the specificity of those individuals or their feelings or their worldviews because you’re not asking that sort of question. So of course, without numbers, without generalizations, there would be no social policy.

This is not to say that one can make social policy for happiness or for love. What bill are we going to put through Congress to maximize love in our society? It can’t be done. It must be done in the sense that we need more love in our society, but it’s not going to be done by means of social policy. And it’s not going to be done by means of numbers.

I’ll tell you a little story. [At The New Republic], I was once walking to my office and I passed by a few young people. One said to the other, “You know, she ran into my friend yesterday and she told him that she loves me, which is an important data point.” So I stopped and said, “Excuse me, I promise I’m not prying, but I just want to say that the fact that she loves you is not a [expletive] data point. If you’d like to talk more about this, you can come into my office and we can talk about it. If you don’t want to talk about it, I apologize for the intrusion.”

So he came and we talked about it. I said to him, “If I ask you to express how she loves you on a scale of one to ten and you give me a nine, all that tells me is that she loves you a lot. It doesn’t tell me anything about the quality of her love, the texture of her love, the intensity of her love.” None of those attributes can be captured in a number.

When you come to cultural institutions, it all depends. I don’t believe museums should decide whether to have a Rembrandt or Titian retrospective on the basis of what the dollar cost per visitor would be, because I think such a show would be a service to the culture and a public good. And I think so—I know so—not on the basis of numbers but on the basis of a knowledge of Rembrandt and Titian and of previous generations’ responses to this kind of art.

Cultural policy has got to live with a greater degree of uncertainty and a greater degree of risk than social policy, because in the realm of culture we cannot have a completely lucid, arithmetically clarified environment with perfectly confident predictions about the outcome of the actions we take based on various types of data. We just can’t have it.

|

IYENGAR: One of the things you’re suggesting, with the museums example, is that you hope for enlightened leaders—and that it’s part of the general public’s education, I assume, to know what these great works are. But what about innovation in the arts? It comes back to risk, right? Do we just have to believe enough in the concept of arts and culture to support experimentation and the creation of new works?

WIESELTIER: Of course we do. One has to have a realistic understanding of how the rewards of such experimentation and creation will manifest themselves. A spiritual experience, an emotional experience, an aesthetic experience, is not like a stock. You “invest” in these experiences, and they take time to sink deep into the minds and hearts and souls of the people who experience them. We don’t know what they will produce as a consequence of what they saw, or when, or how. A person can be transformed by something he or she sees in a museum. But that doesn’t mean we’re going to know about that transformation immediately or maybe at all. We certainly cannot predict it or quantify it or translate it into an action plan. Maybe all the museum will have produced is a more sensitive human being and therefore a better citizen.

Cultural education is an essential part of the formation of a good citizen. We’re not just talking about the cultivation of the self for the self’s own ends, which is also one of life’s objectives, we are talking about the cultivation of the self in society. We want citizens who have developed imagination and developed powers of empathy, and who know about patience, and listening and looking, and who are open to the full range of human experiences that only art can provide. These people are not only better thinkers and artists, and not only better friends, lovers, and spouses—they are also better voters.

I’ve come to realize over the years just how important imagination is to morality, not just to art. The reason is that we cannot undertake ethical action to relieve suffering that we have not ourselves experienced unless in some way we can imagine it. Otherwise our ethical action would be limited by the accidental circumstances of our existence, and by our narcissism. Our hearts would never break for any predicaments but our own. The imagination is what carries one beyond the confinements of one’s own experience to a larger understanding of all the pains and the pleasures that are available in the human world, and that is one of the foundations of moral action, of social action.

The more we educate ourselves by means of the arts, and expose our citizens and our children to the full range of the human heart, the more decent and wise we become, individually and collectively.