Carrying Our Culture Forward

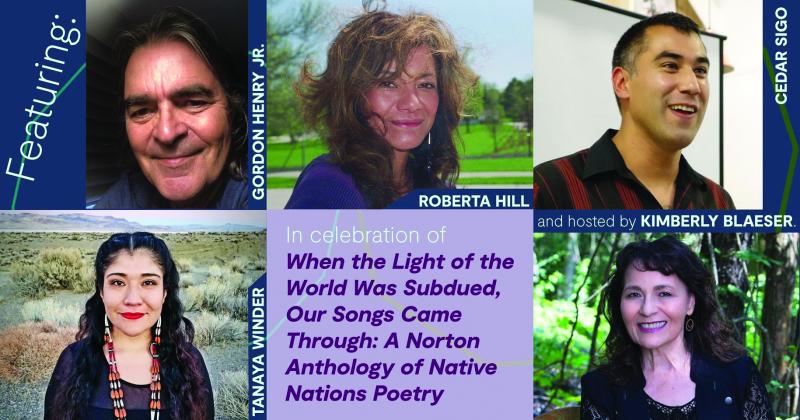

An In-Na-Po reading at Printer’s Row Literature Festival in Chicago, Illinois. Photo courtesy of In-Na-Po

When poet and professor Kim Blaeser (Anishinaabe) was a young girl, her family would travel hundreds of miles from their home on the White Earth Reservation in Minnesota to Montana for her father’s work. She recalls these car trips as being filled with storytelling, singing, and poetry as her father would recite “The Village Blacksmith” and long passages of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” from memory.

Blaeser has carried her family’s love of language throughout her career as a poet and scholar. She is a past Wisconsin Poet Laureate, author of five poetry collections, and currently serves as a professor at the University of Wisconsin–Milwaukee and MFA faculty for the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe. Blaeser is also founding director of the nonprofit In-Na-Po—Indigenous Nations Poets.

In-Na-Po is a national Indigenous poetry community that supports emerging writers and Indigenous poetic practices. The organization is part of the Poetry Coalition, a group of more than 25 independent poetry organizations that promote poetry’s societal and artistic value.

Blaeser spoke to the Arts Endowment about the importance of poetry and art in her life and Native communities, the founding of In-Na-Po, her hopes for its future, and the role of poetry in preserving Native languages and affirming tribal sovereignty.

RHYTHM OF LIFE

I should introduce myself the way that’s proper, which is, Kim Blaeser nindizhinikaaz. Anishinaabekwe nindaaw. Gaa-waabaabinganikaag nindonjibaa. Migizi nindoodem.

I grew up on the White Earth Reservation in northwestern Minnesota. That’s my home place, and in my earliest years, I grew up literally in the middle of nowhere at my grandparents’ farm, 26 miles by horse from the nearest country store. It was like I was living in another era; it was another culture, and it was very alive with oral stories and word play.

I had this lively family of storytellers. I think there’s something about that that feeds you. I was nourished in my love of language, in my love of stories and songs and word play, and I really think of that as the foundation for the work I do now. I began writing poetry when I learned to write, and I’ve written poetry my whole life. When I was too shy to speak, I often turned to language on the page or invented things in my head. Reciting poetry out loud was not an unusual thing in our house. The rhythm of my life was around language and performance and how that was a part of community.

When I think about Indigenous literature broadly and I think about the arts in Native communities, I always talk about them as being both affective and effective. For poetry: it’s beautiful as language, but it also does something in the world. Those two things are happening simultaneously, and that’s part of a really important foundation in Indigenous literatures. The way that our arts have always been practiced, they’re nurturing to the community. They help us flourish as people, they make us stronger, they reinforce our teachings.

Kim Blaeser, founding director of Indigenous Nations Poets, or In-Na-Po. Photo by John Fisher

"The idea is not to segregate Indigenous writers from the rest of poets or the writing world. It’s to help them find their way within those communities."

Harold Bloom introduced that phrase “anxiety of influence,” and I always think of Native arts as not engaged in this great anxiety of influence but instead engaged in a celebration of influence, because we carry forward the stories, the teachings, the songs, the voices, the history, the land traditions. All of those parts of our culture are not something we want to break ourselves from. We don’t say, “Oh, I’m going to be different from these voices.” We say, “Oh, my gosh. These voices are so important to me and let me amplify them and expand on them and show how they apply to the world we live in now.”

I’m not suggesting no one is out there doing something innovative, because there’s all kinds of innovation, but there’s a foundation that is important. We’re not abandoning; we’re adapting to new materials and philosophically we’re adapting to new circumstances. We’ve always been taught that art is a gift, and it’s a gift that helps us in our living.

IN-NA-PO, THE ORIGIN STORY

A few years back, at the Association of Writers & Writing Programs (AWP) conference, I had a long conversation with Jen Benka, the head of the Academy of American Poets. She talked about the Poetry Coalition, this wonderful gathering of more than 25 organizations—including Cave Canem, Kundiman, and other organizations that support writers from particular communities, including poets of color—and she said, “I’m holding a space. I’d love to have a Native organization.” I said, “All right, I’ll do that.” Honestly, it took a while for me. It’s a huge undertaking.

We actually founded In-Na-Po in 2020. It’s a national Indigenous community, mentoring emerging writers but it’s also nurturing the growth of Indigenous poetic practices, which aren’t always exactly the same as other poetic practices. That means supporting sovereignty, supporting Indigenous languages, and then in general, supporting and raising the visibility of all Native writers—especially those early writers who continue to influence the work we do now as well as all of the young writers who are just touching pen to paper or fingers to a keyboard.

The idea is not to segregate Indigenous writers from the rest of poets or the writing world. It’s to help them find their way within those communities. Whether that’s publishing or funding or attending writing retreats, it’s showing them how to get there, and also letting them know that we have their back.

We’re going to have our first mentoring retreat in Washington, DC, in April 2022 at the Library of Congress. Joy Harjo will be finishing out her term as U.S. Poet Laureate, so she’ll be with us for these five days. It’ll be a space [where Native writers] don’t have to explain to somebody else who they are, where they come from, how their art is connected to their culture. They can do the work, and not have to stop and explain the work, or justify themselves, or create a safe zone around themselves.

Paul Chaat Smith is a Comanche author, and he’s an art curator. I often quote him, because he says, "Artists are deeply respected in the Native world. We ask of them just two things: make fabulous art, and lead the revolution." That’s how I’m seeing what we’re doing now.

In-Na-Po reading event held virtually and hosted by Woodland Pattern Book Center. Photo courtesy of In-Na-Po

LANGUAGE AS RESISTANCE

A lot of Indigenous writers are allowing their language to come into their writing. I’ve always gone between Anishinaabe and English, but also inhabit that kind of middle space—code-shifting—where you’re distorting one or the other, which is what people do when they live between languages. There’s this sense of claiming. It’s a celebration, but you are also reinforcing your own knowledge of the language.

Writing this way is an act of resistance. It is also self-preservation. As Native writers, we’ve had to shut off certain elements of our experience, and those are the doors that are being opened again. We’re saying, "No, this is welcome." I talk about with my students the idea of "archive," and how there are things in and outside the archive. Our oral stories, our songs, our oral poems, have not been in the archive. But Indigenous people are saying, "Huh! We have our own archive. We’re celebrating our own records, our own memories, the way that we keep our traditions." That is another act of sovereignty.

There are a lot of those subtle ways that we might enact sovereignty, but I think that you can’t read Native literature, poetry, without seeing that poets are also engaged in the politics of the time. They’re engaged in critique of historical genocide, inequity, all of those things; and they are claiming, in so many different ways, tribal sovereignty. I feel like In-Na-Po could not separate those two missions, that they are just bound together; that, as writers, we are writing for and with our nation, and that means we are a nation. That means that we belong to that tribal nation, as well as existing within the United States.

For example, I recently wrote about ma’iingan, or wolf. Since the wolf was delisted [from the endangered species list], there have been hunting seasons, including here in Wisconsin. For the Anishinaabe people and many tribes, we have a certain reverence for the wolf. We actually have a Wolf Clan, and we have had a long-standing relationship [with the wolf]. So, that slaughter just isn’t acceptable for us. My reservation, White Earth, passed a law and made White Earth a wolf sanctuary. That is another arm of sovereignty—we make our own laws about how we will behave, but we also want to share what we’ve learned over centuries with those other people who may not have had the same relationship, or teachings, or understanding.

But if we only practice these things within our own territories, that’s not going to keep safe other places. A lot of Indigenous people live in urban areas now, and the sovereignty of our languages and our belief systems should extend to wherever Indigenous people are. The elements of Indigenous poetry come out of some of those tribal teachings; the Indigenous knowledge is not only for our nations. Poetry from Indigenous nations remembers and celebrates our resilient cultures; it also maps a path, a way of being in today’s complex world.