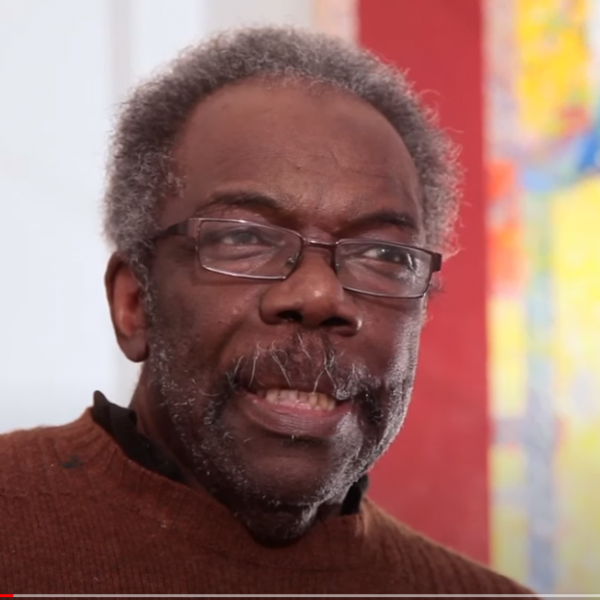

Carl Stone

Carl Stone. Photo by David Agasi

Carl Stone is one of the pioneers of computer music, known for his sampling and manipulation of both recorded and live music. Born in Los Angeles, he studied composition at the California Institute of the Arts with Morton Subotnick and James Tenney. He has been a composer of electro-acoustic music since 1972, performing live with his computer as his instrument since 1986. He has received grants from the Rockefeller Foundation, the Foundation for Performance Arts, and the National Endowment for the Arts, and was commissioned to compose a work for the 1984 Olympic Arts Festival in Los Angeles. He divides his time between California and Japan, where he is on the faculty of Chukyo University. We talked by Skype with Stone several days after his performances at the Getty Center in Los Angeles as part of the Pacific Standard Time exhibition series.

WHAT IS INNOVATION

I guess innovation to me is the development or the creation of either techniques or processes or technologies that somehow move artists or performers or audiences forward. I know some people say innovation should be sort of large and earthshaking; I believe that innovation can be incremental.

I think that everything that I've done, in the broad scheme of things, might incrementally push things forward. But at the same time, I really can't take credit for anything that I've done as being the only person, or even the first person, to do it. I found out -- especially when I was in my formative years and really thinking about new approaches and new strategies for composing and for performing -- that basically everything I had done was being done, or had been done, by an elder or by a colleague on another coast.

I'd like to think of myself as forward-looking, and I'd like to think that I've done my part in moving the aesthetic forward. But I can't honestly claim to be a true innovator in the way that some other people have, like John Cage. He caused us to challenge the fundamentals of what is music through his approach to breaking down the barrier between performer and musician and composer; the barrier between performer and audience; and also very concretely in his development of the prepared piano. Which is a brilliant innovation I think, because it allowed one piano to then serve as an entire percussion orchestra.

|

You can hear some of Carl Stone's music at these two sites:Facebook | Sukothai |

THE MUSIC I MAKE

I try to reach out amongst many different genres; rock or traditional music from numerous cultures around the world; or from classical music or from pop or wherever...and what kind of music that becomes is something that I to this day cannot tell you. I mean, it's a big problem for record stores, or even for iTunes or Amazon, to come up with a category for what I do. It's not exactly classical music; it's not classical electronic music like you would find in Europe. It's not improvised music as it's defined. It's not jazz, it's not rock. What is it? I don't know.

My basic technique is what's come to be known as sampling. That's where found or selected musical materials serve as a compositional starting point for what I do. I perform most of my music myself, using a laptop, and I do it in real time. I use improvisation, but usually within a kind of overall composed structure, where I fill in the details in an improvisational way. I use repetition a fair amount, and I often limit my musical materials. This has caused me to be what I consider to be kind of miscategorized as a minimalist composer.

I'm interested in technology. I mean, I'm interested in technology as an inevitability of my process; it's not its raison d'être. It's just something that I kind of have to do in order to make the music that I want. And I want people to forget that I'm using a computer. I'd like people, when they either listen to a recording or go to a concert, to at some point just stop thinking about the process that's being used, the technical process, and listen to it simply as music qua music.

I use recorded sounds, very often music, as a starting point. And I'm interested in radical transformation. I especially work with time, and also with the spectra of sound. I'm interested in mathematics, and I'm interested in games; structures like palindromes and canons very often show up in my work.

[For] my signature pieces, I did become almost obsessed with some piece of music, or just some fragment of a piece of music, and then develop a composition around that, usually as a way to kind of explore what's going on in the music almost at the molecular level. I will delve in and find some process that allows me to explore the inner workings or the inner molecular dynamics of a sound or of a piece of music.

But that's not always the case; sometimes I do it the opposite way. I'll be programming and have sort of an idea of a process, an abstract idea of a process, and I'll build it in software, and then I'll plug music in and see what the results are. So in that case, it's kind of the complementary opposite where the musical material itself is not as important as what the process is; as opposed to pieces of mine where the music is really what it's about, and the process is a way of exploring it. I work both ways comfortably.

|

COLLABORATION

The concert that I did last Saturday night [at the Getty Center] had pieces that involved other performers. And in one case, the piece "Hoang Yen," which Gloria Cheng performed, she had a score that I wrote for her. And I'd take her performance in real time and I'd process it. And so the piece developed slowly. She doesn't really change that much what she's playing based on what she hears. She's following a score.

Another piece, "A Te Geuele," which I did with the pipa player Min Xiao-Fen, that's virtually improvised. We had a kind of graphic score, and we agreed how we would start and how we would end, and a certain couple of points in the middle. But all the other details were completely open; and we're listening to each other and reacting to each other. But again, I am sort of capturing her sound. I'm cutting it up. I'm repeating it. I'm moving it around in space. I'm processing it: radically at times and subtly at other times.

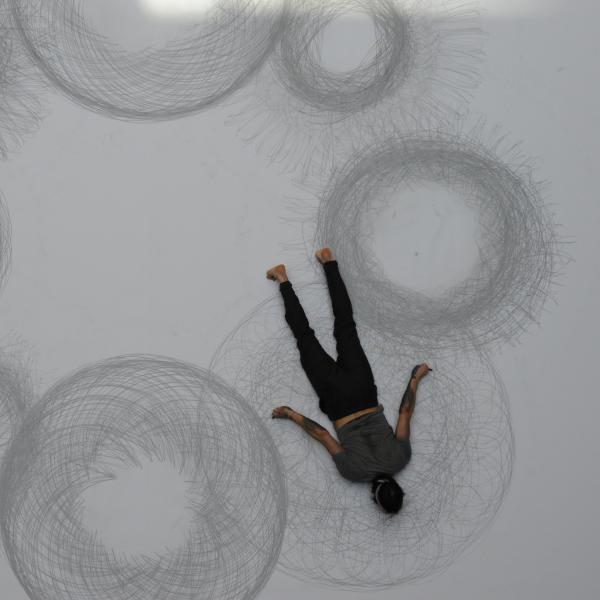

It's only been in the last ten years, since I moved to Japan, oddly enough, that I started really improvising and developing my chops, to use a jazz musician's term, as an improviser. Before that I would improvise, in the sense that I would write these pieces and then I would fill in the details as I performed them. But 99 percent of them were solo works or works for other artists, like a dancer or choreographer or whatever. But in the last ten years I've done a lot of collaboration, real-time collaborations, with other musicians. We improvise together, like a jazz unit. The thing that's sort of maybe a little bit unique is I'm usually sampling them as they perform.

FELLOW TRAVELERS

I think [the tie between my sampling and hip-hop] developed out of a zeitgeist, and not because I was listening to early hip-hop; and certainly I don't think any of those early hip-hop guys were listening to me. I've been pretty much under the radar in terms of popular culture. It was a zeitgeist that was enabled by the technology of the LP record, first of all, and the CD recordings, computers...a kind of post-modernist aesthetic where materials from the arts themselves were used as functional stepping stones and building blocks for new works of art. It goes back to sort of the early hip-hop artists like Robert Rauschenberg or Andy Warhol, in a sense. They were hip-hop artists too because they took signifiers from popular culture, and they made something new from it.

I think of artists in sort of similar sonic territory -- thinking broadly, and not just focusing on one aspect of my style -- I feel kindred with an artist like Otomo Yoshihide and some of his work; maybe not so much what he's doing now but what he was doing back in the '90s. There's a Bay Area artist by the name of Wobbly, and a British artist who goes under the moniker of People Like Us. [And there's] Ikeda Ryoji, unsung father of glitch music, because he took sounds that were the detritus of digital music -- all the errors, the clicks, the pops, the errors that exist in digital recording technology -- and he turned them into music.

My teacher, Morton Subotnick, would be another person who I consider to be an innovator, even today. He's well into his 70s, but pioneering new interfaces for performance. He was doing that back in the '60s, with new approaches to live electronic music, and especially using electronics as a way of integrating with a live instrumental performance. Luc Ferrari, because of what he did bringing the world soundscape. He adopted some of the ideas from R. Murray Schafer, and has caused us to look at the soundscape of the world through his use of field recordings in composition and music making.

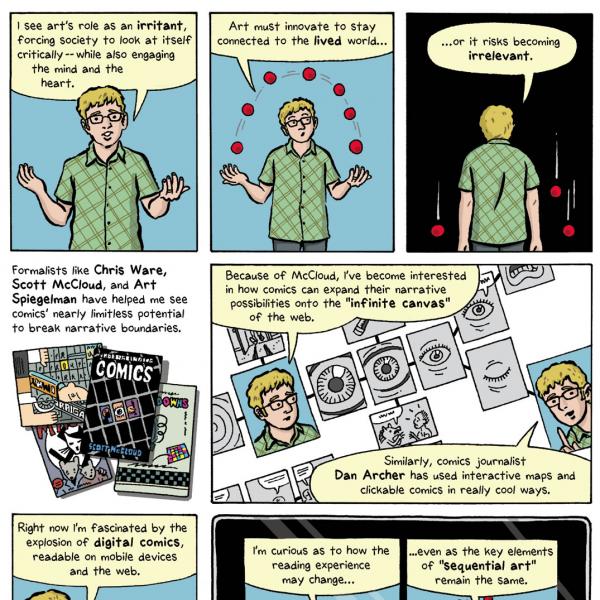

And then, he's not maybe always thought of as an artist, he's a programmer, and that would be Tim Berners-Lee, who is the chap who basically developed hypertext. This is an incredibly important development not only in networking but communication technology; and I think ultimately in artistic communication as well. That concept, and what he enabled through that, has been true innovation.