Maya Lin

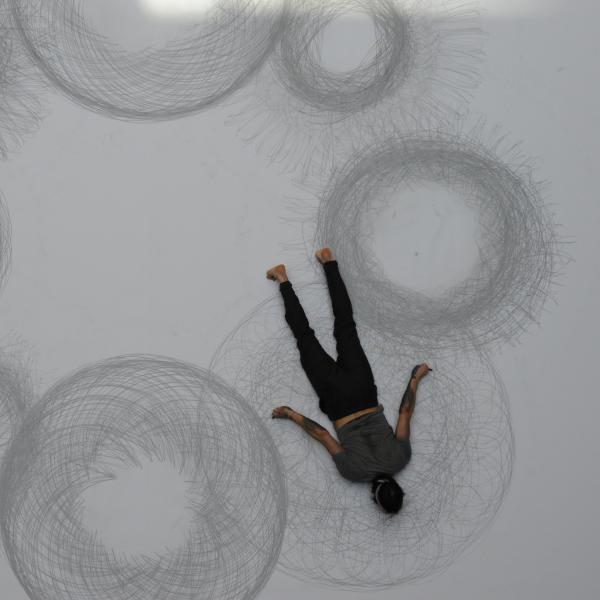

Maya Lin working on the Confluence Project, a series of artworks near the Columbia River Basin in Washington State, along the Lewis and Clark Trail. Photo by Betsy Henning

At age 21, while still an undergraduate at Yale University, Maya Lin shot to fame when she won the design competition (supported by NEA funding) for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial in Washington, DC. A native of Athens, Ohio, Lin went on to earn her master's degree in architecture from Yale in 1986, and has received numerous prizes, awards, and honorary doctorates, including the National Medal of Arts in 2009. Throughout her career, she has moved fluidly between the realms of art, architecture, and memorials, maintaining a steady focus on the landscape and environment. Whether designing sculpted outdoor earthworks or private residences, Lin reinterprets the world around us into visually stunning, intellectually compelling pieces. She is currently at work on her final memorial What Is Missing?, a multiplatform piece which will call attention to current environmental issues. In her own words, Lin discusses her creative process and the "tripod" nature of her body of work.

ON INNOVATION AND CHANGING PERSPECTIVE

| To see some of Maya Lin's work, visit her website. |

Innovation could be everything from pure invention to getting us to look at materials that we think we know and getting people to rethink [them]. I like to co-opt the familiar. I like to debunk simple assumptions, sometimes about the everyday. For instance, a lot of my artworks focus on the environment. If I look at a river, I look at the entire length of the river. We tend to pollute what we don't see and what we don't own. Based on ecological terms, what's downstream from you? None of my concern. What's upstream? People focus on what they can see. So I started a whole series on rivers that tries to get you to think of a river as a living unified organism. In order to protect it, you have to see it in its entirety. Getting us to see the world around us in a new light is a key part of my definition of innovation.

I'm almost heartbroken that we've taken art out of primary education in schools. It's a voice, it's a language, it's a way of expressing ourselves. Whether you become an artist or not, I think we all will benefit from letting art teach us how someone else looks at something, how someone reacts to something, how sometimes you can't quantifiably understand what art is doing. If any art form, anything, gets us to take a moment's pause and look at something afresh, that's got to be a good thing.

DICHOTOMIES

I always try to focus back to the personal, the individual, the one-on-one. I think that's very unusual for someone who works in fairly large, very outdoor, very public spaces. You begin to flip the private into the public realm. That happens throughout my body of work, where there are real dichotomies [and] ambivalence. I like being on the border of things; I like to live right on the boundary between opposing things. There's a tension there that I like. Science and art. Art and architecture. East and West. How can I make a rock feel lightweight? How do I make a rock wall look transparent? It's opposites. It's things that, again, you might not be considering. Public monuments that are exceedingly private. That's something that happens throughout my work. I tend to balance between left side and right side of the brain thinking.

ON WRITING, ART, AND ARCHITECTURE

I start with writing, with all my works. That's something that has been a part of my work from day one. I tease out some underlying goals before I ever try to imagine what the shape or the form is going to be. And I study and I research and I research and I study, and then I try to forget consciously all that I have learned. Then I start making.

[Art and architecture] complement each other. For me, making art is like writing a poem. It's quick. It's a singularity of thought that has to be pure and has to be strong, whereas architecture is more like writing a novel. Of course it is an art as well, and you have to make sure the main theme is working. But you also have to literally get the mechanics of every sentence and every paragraph and every chapter. They're very, very different forms of tapping into the creative processes, and I love both. That, I think, is also that left side/right side of the brain thinking, which I go back and forth on. Do they inform each other? Absolutely. Do I like to keep them separate? Absolutely.

When I'm making art, though I'm studying and analyzing scientific data, in the end it emerges more from the hand. [With] architecture, you have to get to the soul of it. But at the same time there is so much detail and so much minutiae. You have to be careful you don't get lost in the minutiae. You have to pull and tease the soul out and keep that pure and strong. At the same time, there are millions and millions of details you have to worry about. The monuments are the in-between ground for me. They balance.

THE TRIPOD OF FORMS

I am proud of [the Vietnam Veterans Memorial]. But since I didn't really want to spend my life making just memorials, I knew I had to define myself outside of that arena. I do think as a society we love to compartmentalize. We like to specialize. I knew it was going to be a longer time for me to create, both in my artworks and in my architectural works, enough of a balance for people to begin to see my body of work as a tripod, with the memorials sort of being in between art and architecture. [The memorials] are a functional art, but their function is purely symbolic. I just had to be patient in order to begin to produce a body of work in all three realms, so that people could recognize how committed and serious I was [to each realm]. One could always argue that [memorials are] going to be my most public work, and that many people will only see that of me. But in the end, I do what I'm compelled to do. I have made things my entire life, and will continue to do so.... Someone gave me really good advice: don't worry how they compartmentalize you, just keep doing the work you're doing. I've continued along that line.

Formalistically, I jump. I think that's where it's a little unusual, that part of my brain is always working on some architectural projects, and then I can go into the art end of the studio. That's the juggle. Even when I give a lecture about my work, I will talk about all three, because to talk about one without the other two is almost denying and cutting me into a third of who I am. I always start my lectures saying, "My work is a bit like a tripod, and if you remove one of the legs I will not stand up."

I never got up one day said, "I'm going to do this, this, and this." It's just that I couldn't stop making in all three categories. My greatest fear [is] that I'd be schizophrenic; that the three realms would not share, would not talk, would not be coming from the same head, in a way.

Maya Lin's Storm King Wavefield at the Storm King Art Center in Mountainville, New York. Photo by Don Ball |

FOCUS ON ENVIRONMENT

For me, what has remained, and has really gotten refined, is this focus on the environment. It's probably the first thing I ever cared about. My parents can never figure out how it happened. In third or fourth grade, I was boycotting Japan to save the whales. I was sitting in the parking lot of the A&P with a petition to stop seal trapping. I was going to go to Yale and become a field zoologist. I was growing up in Ohio in the '60s and '70s...and all of a sudden you look at the Clean Air Act, the Clean Water Act, and how much legislation changed the landscape. That was a very formative moment for me. Ironically, the Vietnam War was going on, and [the Civil Rights movement]. I was so concerned about how one species could be doing such damage to the rest of the planet without feeling obliged to alter and change. I've always felt that way. Maybe that's the static point in my life.

Can I do something in my lifetime that can help change the way we are, whether it's war or whether it's the environment? Can I help, in a little tiny fraction, make it better here? If I could do something to help us stop degrading the planet, if I could help in any way -- that's what I'm striving to do. I'm extremely optimistic that way. I believe that art can sometimes change the way people think. This is why my final memorial is devoted to raising awareness about what we are losing in terms of biodiversity and habitat. It focuses on what we are losing and also focuses on what can be done to help.