Julie Taymor

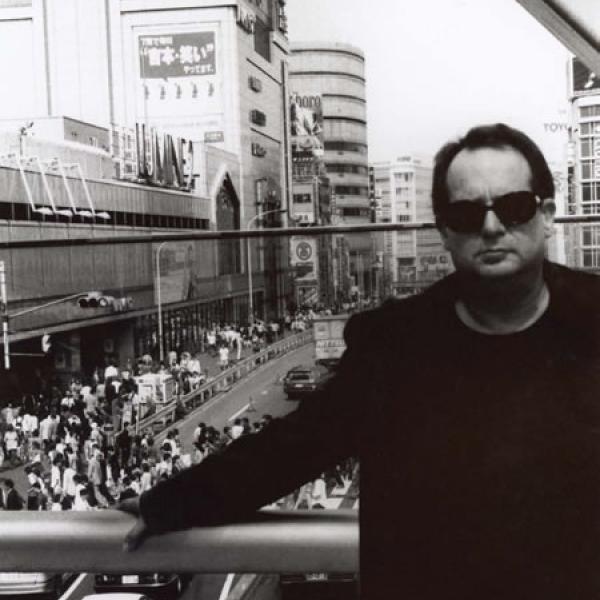

Julie Taymor. Photo by Marco Grob, courtesy of New York Magazine

Whether directing for the stage or screen, Julie Taymor has consistently defied cultural expectations and tested technological limits, reinventing storytelling in the process. She is perhaps best known for her 1997 Broadway hit The Lion King, which earned her Tony Awards for Direction and Costume Design. Based on the Disney movie, the musical utilizes masks and puppetry, an art form Taymor studied while living in Indonesia and Japan as a young woman. Her 1996 multimedia off-Broadway production, Juan Darién: A Carnival Mass, earned two Obie Awards, while early stage works such as The Tempest, Liberty's Taken, andTransposed Heads were recognized with a 1991 MacArthur Fellowship. Taymor has also brought her imaginative touch to other media. She has directed operas such as The Magic Flute and Grendel (which she created with the help of a 1988 National Endowment for the Arts grant), while her filmography includes Titus (1999), Frida (2002) -- which won Oscars for Best Makeup and Best Original Score -- Across the Universe (2007), based on music by the Beatles, and The Tempest (2010). We spoke with Taymor by phone to hear her views on artistic innovation, and how it has shaped her career.

DEFINING INNOVATION

Innovation is using your imagination to go to places that people haven't visited before. It's really taking something that might be familiar and then transforming it. A lot of it has to do with transformation and creating a new taste, a new feel, a new experience. I love to blend forms, so my cinema is very theatrical, my theater is very cinematic. I utilize a lot of different mediums as I move from theater to opera to film. I'm constantly experimenting with both high and low technology.

Innovation isn't something I seek out. I look at the story I want to tell, and I say, "What's the best way to tell that story?" Often you're moved by the medium itself, by the way [the story] is being told. Especially in theater, the art of how you tell a story is often as meaningful to the audience and as moving to the audience as the story itself. So it's a balancing act where the technology or the physicality or the art of it can possibly supersede the storytelling. But the craft of directing is to make that balance.

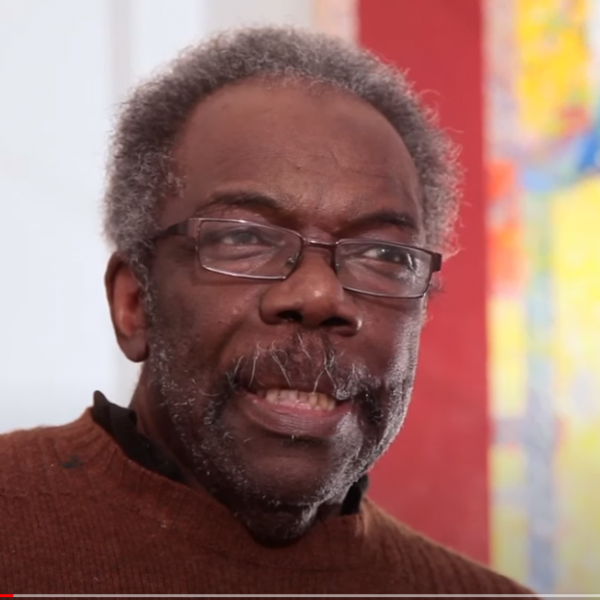

The Lincoln Center Festival 2006 production of Grendel, composed by Elliot Goldenthal with libretto by director Julie Taymor and J.D. McClatchy, based on John Gardner's 1971 novel. Photo by Stephanie Berger, courtesy of Lincoln Center |

ON CULTURAL INSPIRATION

I've always traveled. I went to Sri Lanka when I was 15, and lived with a family there and traveled through India. Elliot [Goldenthal] and I spent time in Mexico when we were working on Juan Darién. I'm doing a piece in Brazil, so I've been to Rio.... Other people's cultures inspire me tremendously. Being open to what I see and hear and smell and eat, and keeping my senses wide open to all different forms -- it's how I am inspired.

When I lived in Indonesia for four years, I would look at traditional Javanese shadow puppetry and how they were using oil lamps to light the leather shadow puppets. I watched as the new puppeteers, dalangs, were changing to electricity because of convenience. That may have been innovative for those artists, but as an outsider I felt that something was lost. So my first theater piece, The Way of Snow, moves from leather shadow puppets and oil lamps into an electric light bulb lighting plexiglass, high-colored puppets. The story was about modernization, and the technique I used showed what gets lost.

There's something about wood and leather and fabric and silk and shadows and fire that is beautiful to feel and see. Sometimes, technology in its packaging is cheap-looking, and it's not organic in any way. All of our computers and iPhones and iPads and televisions are not particularly aesthetically pleasing, but the content and the creativity that comes across in what people create is mind-blowing. So you gain that immediacy and extraordinary digital effects. On the other hand, you lose a kind of humanity. I don't want to lose all of the extraordinary benefits and beauties you get from things that were created thousands of years ago.

I'm always trying to create something new. Not just [with] technology, but in the story. I don't really think people need to see something they already know before they came to the show. If I go to the theater, I want to have a new experience. Even if it's a story I know, I want it to be told in a way that I never expected. I'm always trying to take people to places they didn't even know they wanted to go. Sometimes that can be very difficult when you're in a commercial arena, because people want to make sure that the audience is happy right away. But to break ground and be innovative takes time and it takes patience, and it really is work. The audience may at first not know what they think. But over time, it does pay off. "The bigger the risk, the bigger the payoff" is a very good motto in that world. If people don't take risks and we don't innovate in how we tell stories, whether it's to children or adults, then we're not progressing as humans and we're not progressing as artists.

The first theater artists were shamans, which are doctors of the soul, of the spirit. That's where the origin for theater came from. They were there to understand loss, birth, death, illness, and to take people through the passages of their life. That is something that I hold onto forever: what's it all for, where did it come from, what is its major function? The fun part is how do we tell it in a way that will reinvigorate the story or inspire people to look at that great Shakespeare play from a different point of view?

AN ENVIRONMENT FOR INNOVATION

I don't think you can teach [innovation]. I think you can support it and encourage it. But it really requires the artist or the individual to have the desire to go out on a limb and take risks and be exposed and do things that aren't necessarily safe in artistic terms. You've got to be willing to challenge yourself and others. So the environment for innovation is more critical than anything. I think that you can say, "You are free to go wherever your imagination can take you within the limitations of these means, with what we give you or what you have." But you can make so much: limitation is freedom. You have to encourage people to feel that within those limitations, there are tremendously different directions that you can go.

TESTING LIMITS IN THE PUBLIC EYE

We are so commercially minded that when we think "failure," usually it's [in] box office [terms]. I received the Susan B. Anthony "Failure Is Impossible" Award recently up at the 360|365 Film Festival [in Rochester, New York]. What it meant was that in her lifetime, Susan B. Anthony tried to achieve the right of women to vote. She never saw it in her lifetime. So someone's failure to make one thing work may be an incredible success further down the line.

It's very tough, especially now, for theater people to be in front of everybody with blogging, and the immediate response that people have without thought, without letting things percolate or develop. It's going to be very tough for people to be innovative. It's going to be worse than it ever has been. For instance, when we did Lion King in Minneapolis, we broke down the first week. We couldn't do thorough run-throughs, and we had to write new scenes. But nobody knew about it except for the audience that was there that night. We're in a different time.

I think it's critical that people keep a certain amount of direction and focus during that [online] bombardment. Otherwise, you could fall apart. People are going to need tremendous support -- all kinds of artists -- not to fall prey to the outside pressure. That's one of the hardest things in the performing arts, and more difficult now for everybody.