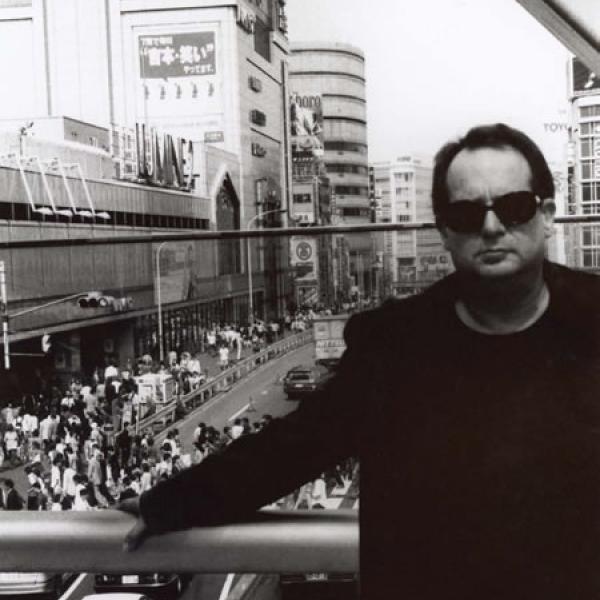

Chris Miller

Chris Miller. Photo courtesy of DreamWorks Animation

In his career at DreamWorks Animation, Chris Miller has been engaged with nearly every aspect of animated filmmaking. He worked as a story artist and voiced characters for projects such as Antz, Madagascar, Shrek, and Shrek 2, eventually becoming co-director for Shrek the Third. He most recently directed Puss In Boots, which received 2011 Golden Globe and Academy Award nominations for Best Animated Feature Film. Below, the California resident talks about the creative forces at work in animation.

COLLABORATION NURTURES INNOVATION

The trickiest [part] for any filmmaker, any director, any writer is applying your point of view. You're collaborating with so many artists. [Puss in Boots] was at least 400 strong on the crew, with a lot of extraordinarily talented people. I learned to really keep an open mind and open approach when it comes to developing a story, and developing a look of the world, [while] making sure I'm communicating a singular pathway and keeping it on track. But always with an open heart, because good ideas can come from anywhere at any time.

I'm really attracted to the process of animation on this level. It is so collaborative and there are so many artists involved that inspire on a daily basis. That in and of itself can nurture an innovative process.

There's that core creative team that's developing the story and the look of the movie. For me, it's about working very closely with my story teams. I lean on them for content as much as I lean on my screenwriter, who's also in that circle. So there's a core ten, 12 people where we really created a strong bond [and] strong trust, and then it just sort of extended out to an additional 375 people. It's amazing to me, especially looking back, that if you've got a good collaborative system going on, and you have that chemistry where everyone's on the same page and understands what direction we're moving in, how 400 artists can automatically feed into the singular path. It's a delicate balance, because I've seen it go the other way. I can watch an animated film that feels like it's put together by 50 voices, or a couple of dozen points of view. They're disjointed.

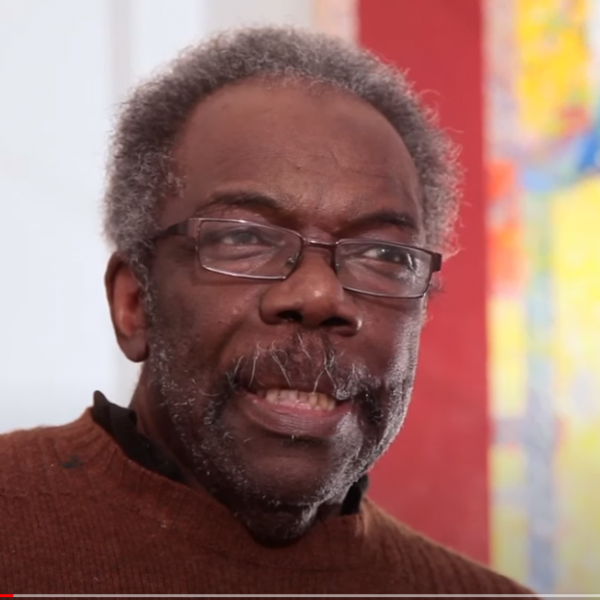

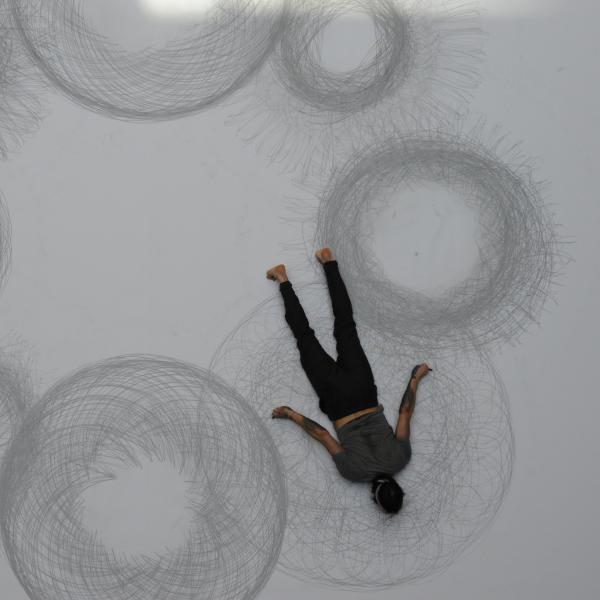

My wife, Laura Gorenstein Miller, is a choreographer. She has a dance company in Los Angeles, Helios Dance Theater, and I created a short for her recently. It was an opportunity to do something that was completely mine. I animated it, I designed it. It was nice... having something that was an utterly singular form of expression. And it was challenging. I'm so used to working with people and creating stuff with people that, I found myself, for a short time, feeling almost a little lost. Obviously I had Laura. What she offered me was something incredible. Most filmmakers would just love [to hear,] "Fill this two minutes of space. Here's the basic idea of what I need. Do what you want." It was strange to have that sort of singular responsibility, and for a while I struggled with it. In the world I'm coming from, we're pretty specific. We keep it open, we keep it loose, but we've very specific about duties and roles. It's strange to have total freedom, to make any choice you want, at any given time, with nothing else hanging over it.

A still from the DreamWorks film Puss in Boots, directed by Chris Miller. Image courtesy of DreamWorks Animation LLC, © 2011, All Rights Reserved |

APPROACHES TO STORYTELLING

The most valuable to me [of my first jobs] was being a storyboard artist. I went to the California Institute of the Arts and studied animation there, and made some short films, and then I worked in some commercials out of school, and even animated a little bit. I realized pretty early on that it just wasn't for me. I wasn't disciplined in that way. It was so precise, and it moved too slowly for me. But I loved animation, I love storytelling, I love filmmaking. So when the opportunity came up to become a story artist and contribute in that way, it was so fulfilling. It's like going to film school every day. You get a crack at so many different aspects of filmmaking by being a story artist. You're the first to sort of visualize the scripts. The way we worked on the Shrek films too, we had so much latitude in terms of creating content and character interaction and character development, that you got a chance to be a cinematographer, a writer. You're blocking out scenes. You're thinking like an editor as you're storyboarding sequences. That was the best training ground to becoming a director.

Far and away the most important aspect of the storytelling [in Puss in Boots] was finding a personal story for the character, something where the stakes felt real, and the emotional journey that the cat was going through felt authentic and true and moving. That's something we struggled with and were challenged by all the way. If that didn't work, the whole movie would fall flat on its face, I think. Finding the emotional truth is the hardest thing. The animation is there to support that idea and make sure it's delivering on it. It's all about storytelling when you're making a movie, it really is.

Technology doesn't drive the filmmaking process; the filmmaking process is driving the technology behind it. New innovations are based on what story point we need to get across, and finding and discovering a new way to do that. I think that's the key to it. It's not a matter of someone in a lab coming up with a new special effect, and then saying, "How can we put that in the movie?" It's always the story that drives that stuff. I really feel like [Puss in Boots] is very successful in this way. It's even using 3D technology as an approach in the film. From the beginning, we never stepped outside of using it as another storytelling device or tool in the toolbox.

KEEPING THINGS FRESH

I'm just striving to find an interesting approach to challenges. If it feels too familiar, I want to do my best to stay away from it, or change it or twist it in some way. I don't know if I can call myself innovative, but that's always my approach: to keep things fresh.

I think it's important that what you do relates to someone; it connects hopefully with an audience's personal experience in some way. I don't think that you have to tell a story, or create something that's utterly different in every way, shape, or form. It's the individual finding their own way of expressing themselves through whatever medium they choose. What makes it unfamiliar or unique or special is the point of view of the artist. That can take the familiar and make it fresh, interesting, innovative, different.

I don't know if [innovation] can be taught. I think it's got to be something that comes from a personal place and a personal experience. The filmmaking process is a great form of personal expression. [Innovation] won't necessarily come from being taught; it will come from doing it and being prolific at it, and challenging yourself, and challenging others you work with. People just have to find their own path, their own way, of expressing themselves.