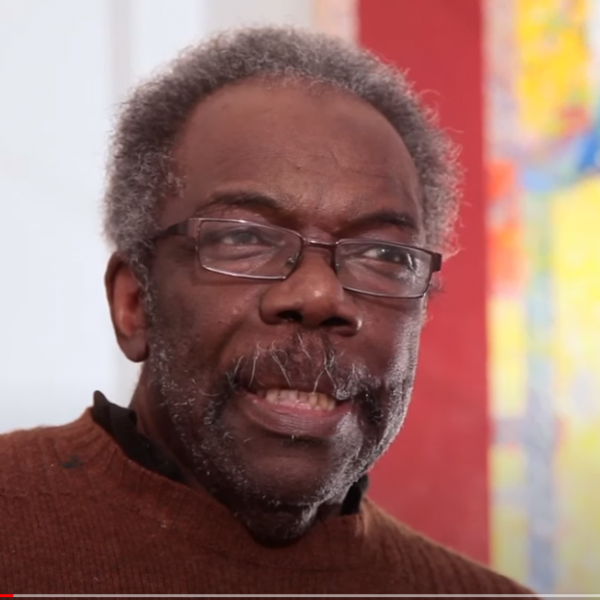

Jawole Willa Jo Zollar

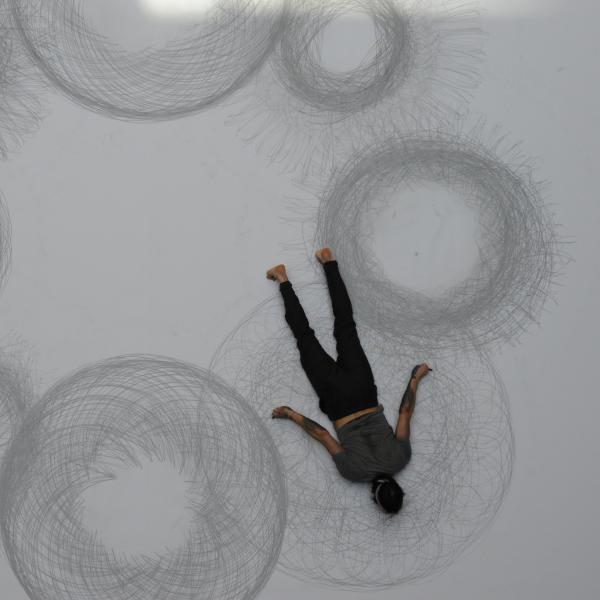

Choreographer Jawole Willa Jo Zollar, a native of Kansas City, Missouri, founded Urban Bush Women (UBW) in 1984 because, as she put it, "I wanted a company [that had] shared values around making work. I really didn't have any definition of what kind of work, but I did know that I wanted to look at the folklore, the religious traditions, and the culture of African Americans and the African Diaspora." Often characterized as a dance company, Zollar's work for UBW is more complex than that, incorporating layers of visual imagery, props, and human-made sounds with dance steps. Zollar, also a tenured professor in dance at Florida State University, has garnered numerous awards, including several NEA choreography fellowships, a Guggenheim Fellowship, and a USA Artists Wynn Fellowship. Urban Bush Women has also received grant support from the NEA, including a fiscal year 2011 grant to support a collaborative work by Zollar and fellow choreographer Nora Chipaumire. Here, in her own words, Zollar discusses her take on innovation and her hopes for the future of contemporary dance.

| Watch some of the Urban Bush Women's performances. |

INNOVATION IS...

I think of innovation as trying new things and trying new ideas, building up off of what you know, but always kind of questioning. There are not a whole lot of new ideas, but are there unexpected ways that you might have an idea come to life? I like work that makes me think, and so I'm always interested in new ways to do that.

Sometimes [innovation is] risky and sometimes it's scary. Sometimes it's provocative in ways that people are uncomfortable. And, for me, that's what's exciting because it's making me think about something in ways that I hadn't thought about it before. I don't have to like it and there may be work that I [decide] I'm not interested in. But that doesn't mean that it's not innovative. So I think that the very nature of it -- you don't know what it's going to be -- I think that's worrisome to people as opposed to exciting.

ON COLLABORATION AND INNOVATION

There's a man named Keith Sawyer who's written a book Group Genius, and he has this quote that I love. He says that, "Collaboration is the secret to breakthrough innovation." And I love that quote because, when you're collaborating with someone who thinks differently than you, who solves differently than you, I think you both end up going to a growing place where you're both pushed. I know the ways that I can solve things just on my own, but when I've got somebody whose brilliant, creative mind solves it very differently than how I solve it, and they watch me solve things very differently, then I think we grow together. What I see is that collaboration is not compromise. That's collaboration, I think, at its worst. Collaboration is about trust and learning together, where you create an environment where you can both learn from one another and then grow to create this thing that is a dynamic entity based on this new relationship with one another.

A SHORT LIST OF INNOVATORS

Certainly, Bill T. Jones, you know, because Bill has worked through so many genres. Now, he's becoming the king of Broadway. But he does concert work, he does opera, he's now doing Broadway musical theater, and he constantly innovates in every form that he goes into. He's definitely someone whose work I pay attention to as an innovator. I certainly think of Liz [Lerman] as an innovator in the work that I saw, Origins, and in her work with scientists. I [think] that scientists are actually closer to artists. They really get artists, more so than a lot of academics, and so I was really just moved by the work she did with them.

However we tell the narrative of the United States, I think the innovators that are in the arts are the under-told story, because I think the innovation in the arts field that comes out of the United States is really spectacular. I'm going to get on my soapbox, but our government, to me, is missing a crucial opportunity. We're entrepreneurs. We hire people. We create jobs. We build this uniquely American form like jazz that there continues to be innovation in. If I go into the jazz arena for innovation, certainly Jason Moran, who got the MacArthur last year, [is] brilliant. [There's] Vijay Iyer and his musicians. There's just so much innovation. I could talk to you for about 30 hours straight on the people who I think are just doing fantastic work.

"WE DON'T TIE OUR INNOVATION TO WHAT OTHERS HAVE DONE."

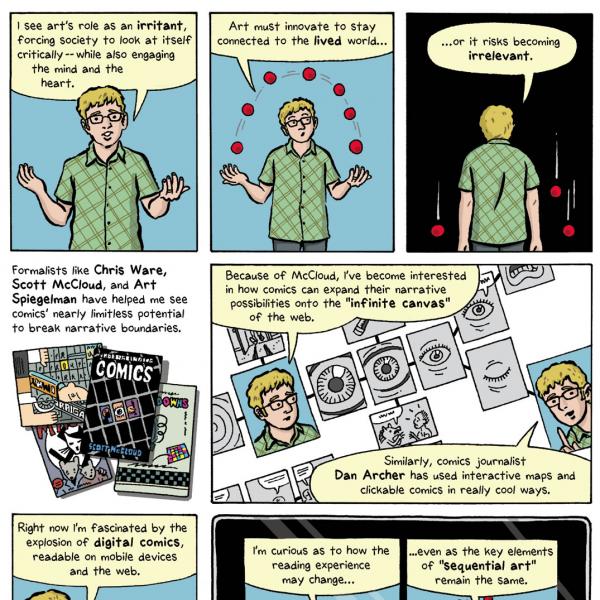

I think that one of the things that we don't do [in dance], and they do this in other fields, is we don't tie our innovation to what others have done. I just went and saw this [artist] recently, and he talked about how he was so moved by the color palette of Gauguin. So he used that color palette to explore a particular idea. You don't hear choreographers saying, "I was so moved by Mark Morris' structure for Mozart that I really wanted to come in the studio and explore that structure and then find out what would be new about it." I think that's a problem, because then our field becomes ahistorical. I'm interested in how we are influenced, that we give ourselves permission to say who we're influenced by. Then that allows our canon to build, and I think it allows audiences to understand something more about us. One of my passions is I would love to be a docent for dance. We in the dance field, we say, "Well, people should just get it." We don't have a catalogue that might give some historical overview of the work, of the artist's work, and where they are in this moment, and what that's informing about this present moment and what the influences are. It's something I'm very passionate about because I think it's a big missing opportunity in our field, and hopefully it will be a place where people begin to really innovate...about how we, in the dance world, particularly the abstract, contemporary world, talk to the world about who we are without feeling like we're dumbing down.

NEXT STEPS

What I'm really interested in right now is something we're calling Project Next Generation. I'm bothered by the fact that if I ask people within the dance world to name five to six choreographers, African-American choreographers with a national reputation, most can't get to six. And that, to me, is troubling. Some of them can't even get beyond four. So we're missing the voice of African-American artists; we're really missing a voice that's a vital part of America.... I want to first have a field convening to figure out why and to do the research to figure out what is [the barrier]. Is it support? Is it that women give up earlier to have families? Is it that some artists are able to find wealth and a lot of artists of color, women of color, are not? Is it that we don't have [a partner that supports us]?

We want to have a convening around it, and then one of the things I want to do is a choreographic lab that really looks at these different ways of making work, again focusing on the voice first and the craft second. The voice and the vision first. What is the innovative, unique thing about a person that can inform their choreographic voice? And then how do we craft that?

WE NEED PERMISSION TO BE INNOVATIVE

I think it's about how you can create a container, as I like to call it, where people have permission to allow their vision to emerge. Students need a lot of permission because they have thoughts and feelings that maybe they're different than what they're seeing everyone else do, so they don't give themselves permission to explore what's unique about who they are. So I like to create an environment where there's permission and then, once you have permission, then we can go into the crafting. I think sometimes people go into the crafting first and then people think they... have to follow certain kinds of rules and I think it diminishes their voice and diminishes their innovation. If you look at children and you ask children to choreograph, they don't know any rules. They do the wildest things because they're not thinking about craft. They're following their vision. I think that the craft, if it's taught too early with too many rules, I think it diminishes innovation.

You have to create a scenario where you're asking [participants] to take a risk and, when they fail, you don't go, "All right, you didn't do that right." My background's in theater so I like to use theater games. One lovely thing about theater games is that they're often set up so you're going to make mistakes and you're going to fail so that you learn that it's okay. I like to start off with play. It's just play, but it's play for an ultimate purpose. Play, for me, is the way that people learn. [If] you're playing hopscotch, okay, so you didn't win that game, [but] you don't get your head chopped off, you know? You continue to play.