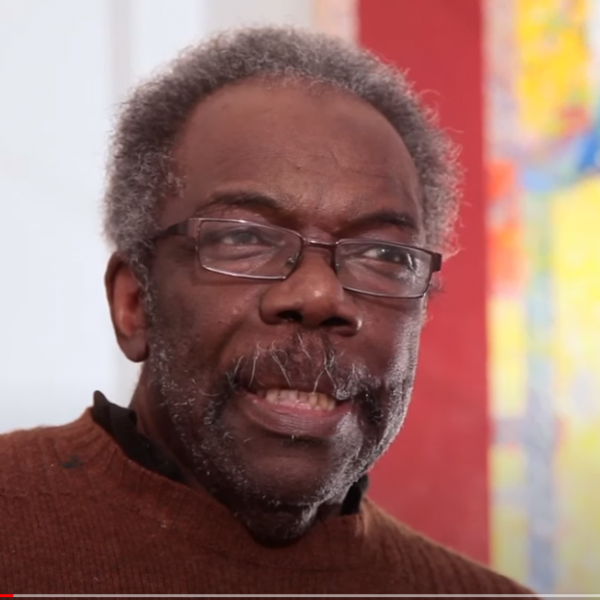

Meredith Monk: Creating “where the voice starts dancing”

Meredith Monk has been an innovative artistic force for over 45 years. She moves among the disciplines of voice, dance, theater, and film with fluidity and ease. In this excerpt from the NEA podcast, Meredith Monk shares her thoughts on innovation and creativity with Josephine Reed.

That's performance artist Meredith Monk. Welcome to NEA ARTS, I'm Josephine Reed.

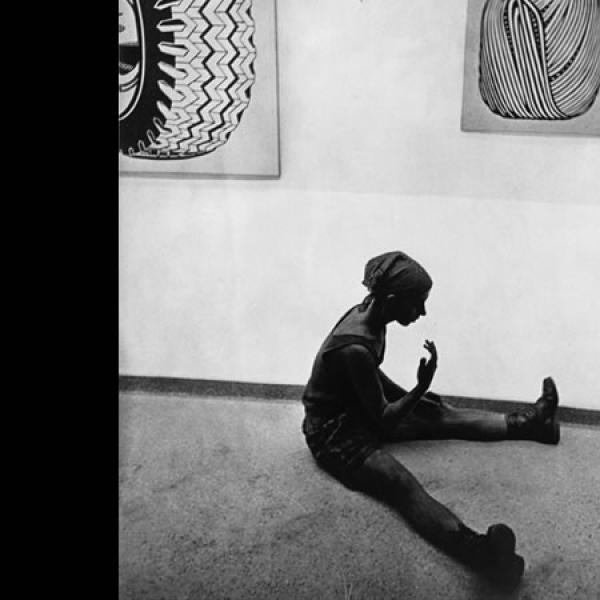

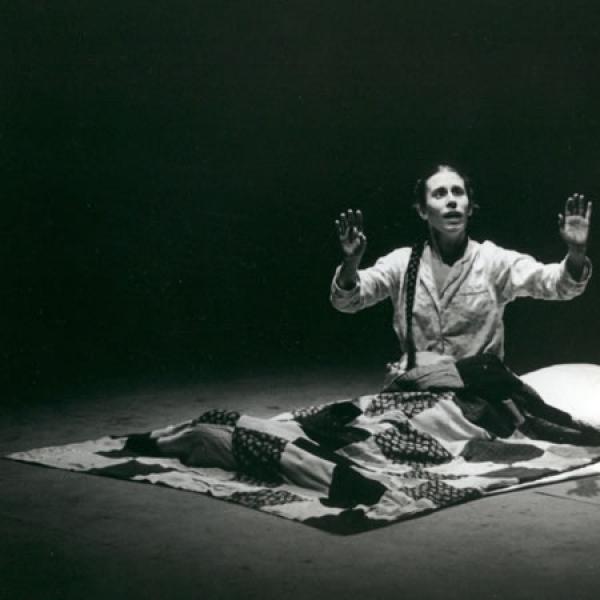

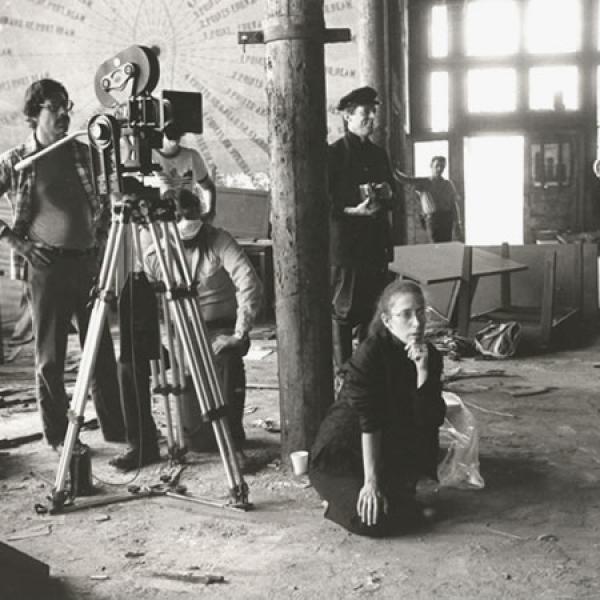

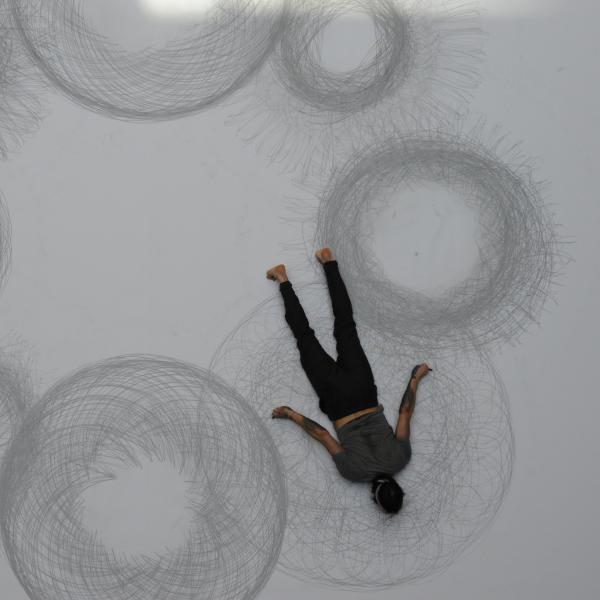

It's one thing to be declared an innovative artist when you're 20, and quite another to consistently push boundaries for over 45 years and create work that continues to be fresh, authentic, and innovative. But that's what Meredith Monk has been doing, seemingly without effort. A pioneer in what's now called "extended vocal technique," Meredith Monk is a multidisplinary artist. She's a composer, singer, choreographer, and director. She also creates opera, music theater, films, and installations. "I work in between the cracks, where the voice starts dancing, where the body starts singing, where the theater becomes cinema," she once said. Admired by critics and audiences alike, Meredith Monk never loses her power to enchant and to surprise. Because innovation is so central to her work, I wanted to know her thinking about it. So that was the question I put to her when I spoke with her in her small country home.

JOSEPHINE REED: You have been called an innovative artist. What does that mean to you? What does innovation mean to you?

MEREDITH MONK: I think it does have to do with trying to find something that maybe has never been done before, or done in this particular way. And yet, it's not trying to make something new for the sake of making something new. It might be going back to something very, very ancient, but doing it in a fresh way. So I feel like innovation has a lot to do with not being afraid to find your own way to doing something, and not depending on something that's happened before you. Or not having something that you know before you start working on it, but literally, really trying to find something. And the moments of discovery are what really keep me going in my life. It's worth all the struggling, just these moments of discovery, to think, "Gee, you know, I've never heard anything quite like that before."

REED: It's interesting to think about the relationship between innovation and tradition, if you will. Robert Pinsky wrote, and he said, "If you want inspiration," but I think you can use "innovation," too. He said, "Don't look back one generation or even two. Delve back into the distant past, to the origins of language and art."

MONK: Oh, I think that has been my inspiration. Thinking about what early utterance would be, before words came in. So, you know, I think that was my original "Eureka" kind of moment, many, many years ago when I first started working with my voice. And I think it's always going back to the origins of utterance, of gesture, of communication, of performance as ritual, of art as worship. All those things, I think, are timeless and they continue to give me inspiration.

REED: You know, we often think of innovators as loners. Do you think that's accurate?

MONK: I think it is a lonely path. I would never say anything different. And I always say that I feel like I was very fortunate, at the beginning, when I was first starting with working with the voice, that I didn't know of any precedent for that way of working with the voice. So I felt always very fortunate, because I had to find my own way, and I think that that's really good. So I think, ultimately, it's very lonely. But I also love the fact that I have a lot of loving performers and a lot of love around me. And I love working with my ensemble who are very much family for me. We have a kind of common language, after them staying with me for so long. And I think that that part of it also, the reaching out, is part of the process, too. Ultimately, you are alone though in your vision. But I think that's great. I mean, we're going to die alone. We were born alone. We're going to die alone. So the way I think about it now at this age is a lot of life is also preparing for death. I don't mean to be morbid about it. I don't feel morbid about it at all. I just feel more about being grateful and loving these precious moments that we have.

REED: Do you think there can be art without innovation?

MONK: Hmmm. That's a wonderful question. I don't think art that -- well, I don't know. Let me try to think this through, because that's an extremely deep question. Because I was just in India, and you know, hearing the traditional and Indian classical music, and knowing that that's going to go on with all the complexity and the beauty, and the specificity of it and the intricacy of it, and knowing that tradition's going to go on is really something that's deeply satisfying. So I definitely think there can be art. I just think there are different kinds of art. And, you know, the art that I'm interested in, as far as what would give me energy or inspiration would be art that is trying to push through some boundaries.

REED: You certainly pushed through the boundaries of artistic disciplines. What appealed to you about interdisciplinary work?

MONK: Well, I think my childhood was interdisciplinary because I came from a musical background. My mother was a singer on radio and her father was a concert bass baritone who had come from Russia around 1890, but he sang in New York at Brooklyn Academy and Carnegie Hall, and he also had a music conservatory in Washington Heights. And his father had been a cantor from Russia. So that was my music background. And then my early training in music was also Dalcroze Eurhythmics, which has a movement component because I had a visual challenge so I wasn't physically that coordinated. So I think my mother had heard about Dalcroze Eurhythmics, which usually is for children to learn music through their bodies, but it was really for me to learn my body through music. So very simple kinds of coordinations like skipping and hopping. And rhythmically I had a natural sense of rhythm and had a musical ear, so it was a wonderful beginning. I always tell people that are starting their children in music training that in my opinion Dalcroze or something like that is a great way to start children. So that was already you could say two art forms, the movement and music, and then I really loved theater as a child so I was in plays and everything. So I think that that was something that I just had these different interests. And then when I went to Sarah Lawrence, I designed my own program in what was called combined performing arts. So by my senior year I was allowed to do that my last year. So I was in the voice department, I was doing opera workshop, I was in the theater department, and dance department. And so I was making pieces of my own that were already starting to combine different elements.

REED: There are so many preconceptions people have about innovation, but it always strikes me that to be someone who is truly innovative you need so much more discipline than someone who goes along a more traditional path.

MONK: I think that it's a different kind of discipline. I remember one time -- I think it was the early '90s --talking with a tea ceremony master in Japan, and we were talking about how within a tradition like that, every step along the way is mapped out. You're learning this tradition and you're really following that with all your heart and so you know what your path is. But with my kind of work, in a way you're trying to follow a path and try to hear what that path is asking from you and it hasn't been charted before. So in between inspirations, it gets to be a little lonely and maybe sometimes a little scary. For me, it's been more trying to go back to the center of my existence and try to hear what my next step would be. That's been my way of really trying to listen very deeply to what the next step of my path is going to be because each step is a new step. And then also I tried very hard, really made an effort, and in a way I think I started getting inspired by this idea at Sarah Lawrence, which is that one of the things I loved about being at Sarah Lawrence is this kind of joy about learning and the sense that learning can happen for your whole life. And it might not be that I remember facts from being there in school, but I remember the joy of finding out something. I got a sense of curiosity there, and I probably was always curious, but this thing about curiosity and learning. And so what I try to do is that each piece I do, I try to start from zero in every piece with no assumptions, no beginners' minds as they would say in Zen Buddhism. And so then it's a matter of working through my fear and anxiety each time, but it's always the way of going through that fear and anxiety comes out to be when you find one little clue or one little question. When you find what your question is, then the curiosity sort of overtakes the fear and then you're basically on the path of that world that you're trying to listen to. It's very hard to talk about these things actually.

REED: But it's very interesting when you talk about listening to that path, or what that path wants from you, because when I think about your work, one of the things I think about is how aptly you use silence in it. And I cannot help but think it has to do with the way you process the work.

MONK: I think silence is just another part of music or of sound. And stillness is another part of movement, so you're always getting emptiness and fullness. Or in Tai Chi, you'd say "full leg," "empty leg." You're always going between those two parts of the same whole. And the contrasts between those two things I think makes both of them clearer.

That was performance artist, Meredith Monk. To hear my entire conversation with Meredith, just click on the NEA's podcast page. Excerpts from Songs of Ascension, composed by Meredith Monk and performed by Meredith Monk and vocal ensemble, used courtesy of Meredith Monk. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.