Opening the Heart and Soul

Twenty years after a truck bomb killed 168 people in Oklahoma City, Jackie L. Jones, then head of the Arts Council of Oklahoma City, can still vividly recall certain images from the aftermath. Sirens screaming as ambulances attempted to break through gridlocked traffic. Shell-shocked pedestrians, wandering in a daze. Traumatized staff members, one whose mother worked in the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building, where the bomb had exploded.

But there are other memories too. A gospel choir that had gathered at the bombing site, handing out sheet music so others could join in. A masking tape mural at the convention center—turned into a staging ground for rescue and recovery operations—made by three young artists in town for the council’s now-canceled art festival. The mural showed people growing wings and learning to fly, symbolic of how aid workers were “making angels,” as one rescue worker noted. There was also a call with then-NEA Director of Design Samina Quraeshi about how design could help Oklahoma City heal from the largest act of domestic terrorism the country had ever seen.

Across the city, Mary Frates, executive director of the Oklahoma Arts Institute at Quartz Mountain, received a similar call from Jane Alexander, chairman of the National Endowment for the Arts at the time. “The Arts Institute should do something, and when you do, we’re here to help,” Alexander told her longtime friend.

***

Jones began working 20-hour days, leaving her office blinds open so that the glare of floodlights illuminating recovery efforts six blocks away would keep her grounded through the night. Her agency’s bank account was depleted with the festival’s cancellation, but Jones was able to secure emergency funding from the NEA and others. With this in place, she helped arrange moments of beauty for those who were most in need. When musicians called, she sent them to the convention center and churches, where families waited for news about relatives. She arranged for the three young artists to make tape murals on hospital room windows of the youngest survivors. The bomb had exploded beneath the Murrah Building’s second-floor daycare center, leaving 19 children dead and sending six to the intensive-care unit at the city’s children’s hospital.

While these efforts provided immediate relief, the larger task of rebuilding would be months in the making. Working with Quraeshi, Jones began to help organize a design charette around the rehabilitation of downtown. The blast had caused $625 million in property damage in an area that had already seen better days. The idea was to create the ideal environment for an eventual memorial, which would be erected where the Murrah Building once stood. “She immediately saw the need for pulling the community together to look forward in some way,” said Jones of Quraeshi, who died in 2013. This included designers, developers, civic leaders, engineers, architects, residents, and the financial community, all of whom shared their visions and concerns over how a rebuilt Oklahoma City might take shape.

***

|

While the design charette would address an entire city’s needs, the Oklahoma Arts Institute at Quartz Mountain decided to focus their efforts on those immediately impacted by the bombing. Through the years, Frates noted, much of the work created at Arts Institute workshops “reflected painful life experiences.” In particular, she remembered the Art Institute’s director of music, who lost his 12-year-old daughter to terminal illness. “After her death, he attended a writing workshop at Quartz Mountain and told me that it not only helped with his depression, it saved his sanity,” she said. “If it could help our students who happened to be artists, couldn’t it help people who were desperate to express themselves and had no way to do so?”

With this in mind, she began to ruminate on organizing a workshop designed specifically for survivors and relatives of victims. When she proposed the idea to Arts Institute leadership, there were the expected concerns about funding, and whether staff members were equipped to work in such an emotionally raw situation. On the other hand, “Shouldn’t we try and help if we could?” Frates asked. Staff members unanimously voted to push forward, and the Arts Institute found itself with six months to plan “A Celebration of the Spirit,” a fourday multidisciplinary workshop for 140 adults, teens, and children.

With funding from the NEA, the Arts Institute drew artists from around the country to facilitate. As a precaution, mental health workers were also stationed in every studio should participants need a professional ear.

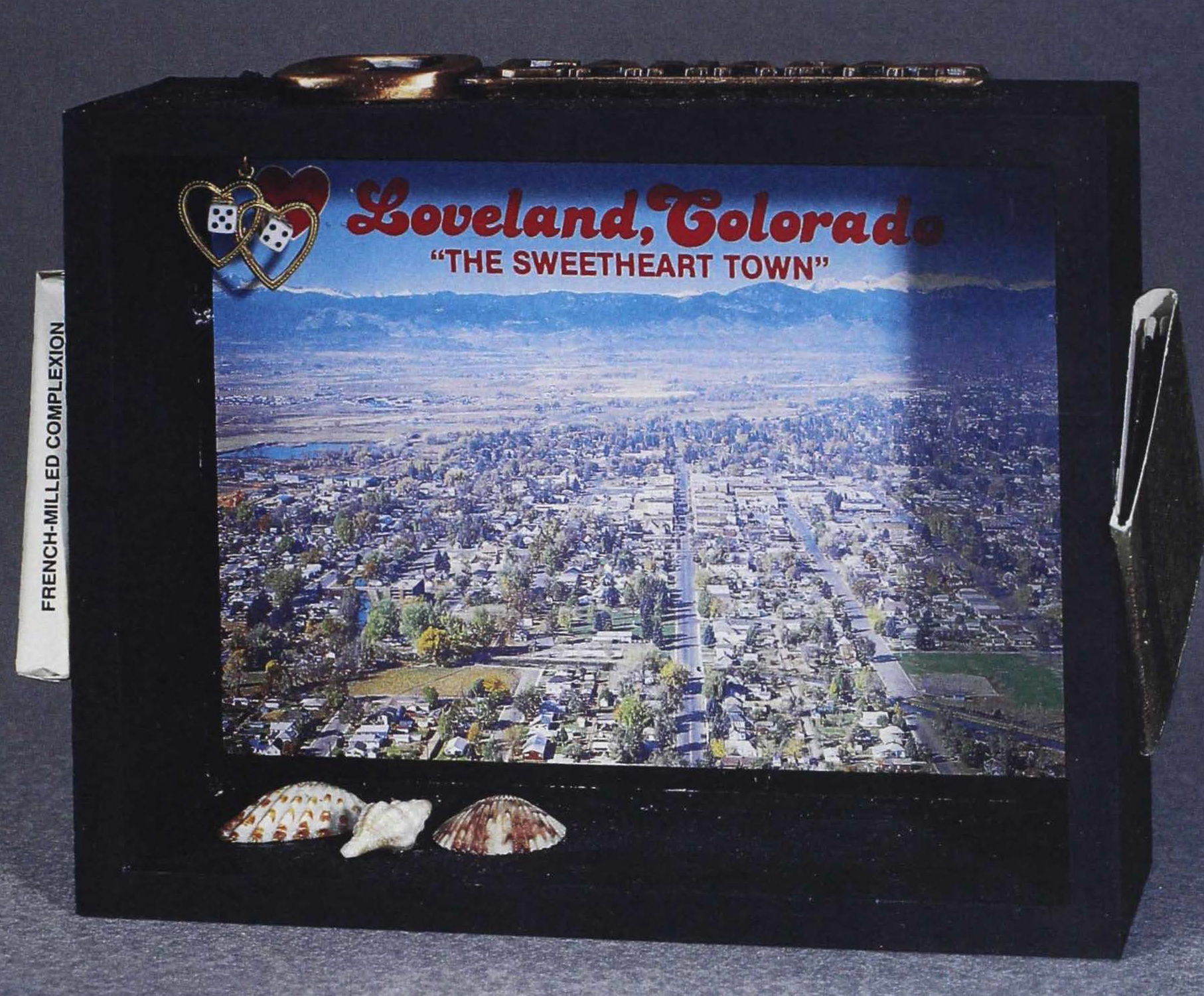

As it turned out, this wasn’t necessary. “Although there were tears, there was a definite trajectory of positive emotion,” said Frates. “It felt good. It felt right. It was working.” Participants wrote personal essays and poetry, wove Cherokee baskets, and made memory boxes, masks, and collages. There was also gospel singing and dance, and a special “arts adventure” for elementary-aged children.

Although Frates stressed that the workshop was not art therapy, she said there was no doubt that the experience offered therapeutic value for participants. Barbara Williams, who lost her husband in the blast, wrote, “My poetry classmates and my instructor have made me think, let me talk, and cry tears of joy instead of sadness.” Cecil Williams, who worked a block from the Murrah Building and lost a close friend and suffered long-term health issues, wrote in his journal, “At Quartz Mountain, I laughed and smiled for the first time in months.”

But the event was more than just a feel-good experience. Facilitators held participants to the same standards that they would professional artists, and the results corresponded in kind. “The faculty expressed amazement that the art was of such high quality, some even better than that of their MFA candidates,” Frates said. So good, in fact, that she and her staff thought it deserved to be showcased to a wider audience. “This work told a powerful story about the ability of the creative spirit to build hope and faith in the future and to create community. It was a story that deserved to be told outside Quartz Mountain.”

In a powerful validation of these workshop participants as artists, an exhibition of their work was organized at the Oklahoma State Capitol, before touring to nine other cities around the state. Most people, Frates said, associated the bombing with objects such as stuffed animals and trinkets that had been left at the bomb site as a makeshift memorial. The exhibition, she said, was able to provide a different sort of understanding and meaning to those who attended. “It’s what art can do,” she said. “It can open the heart and the mind and the soul to actually be there without your having experienced the blast.”

***

As survivors began to heal, so too did the physical city, as the design charette was equally successful. “What they did has had an amazingly long-range impact on Oklahoma City,” said Jones. For instance, one idea that emerged from the charette was to revitalize a section of downtown that had boomed in the 1920s and ‘30s with car dealerships, but had fallen into decline by the 1970s. “They said, ‘We could create something called Automobile Alley,’” Jones remembered. Today, the area is indeed called Automobile Alley, and is home to restaurants, shops, galleries, and loft apartments. The charette results were ultimately turned into a written report, and were showcased at an exhibition at the National Building Museum in Washington, DC.

As the city began to transform rubble into tangible signs of resilience, it paved the way for Jones’s next venture: overseeing the design of the memorial itself. “The art of commemoration is very specific,” said Jones. “It has to be specific to that moment, that people, that community. The challenge of figuring out what that was for Oklahoma City—my city—was something I really wanted to take on.” The winning design featured a reflecting pool bounded by two large gates, representing 9:01 and 9:03—the minute before and minute after the explosion. One-hundred sixty-eight empty chairs (including 19 smaller ones for the children who were killed), signifying the empty seats at dinner tables, are configured in the shape of the building’s fracture.

When the memorial was dedicated in 2000, the first exhibition in its gallery was A Celebration of the Spirit, featuring the work made at Quartz Mountain.

***

|

Today, the memorial has become emblematic of Oklahoma City, and it ranks as one of the area’s most-visited sites. The materials from A Celebration of the Spirit remain in the memorial’s archives, a dual celebration of those who were lost and the strength of those who survived.

The experience marked the beginning of a new trajectory for the NEA as well. After the 9/11 terrorist attacks, the NEA provided emergency funding for arts organizations in the epicenter of the New York City attacks, as well as supporting the ARTifacts: Kids Responding to a World in Crisis project, where New York City-area students created artwork in response to the devastation. From 2004 to 2009, the agency conducted Operation Homecoming, which offered more than 60 writing workshops to troops, veterans, and their families to help them process and communicate painful experiences. In 2011, this initiative evolved into a formal Healing Arts Partnership with Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Through this partnership, troops with post-traumatic stress disorder and traumatic brain injury would be offered writing workshops to help give voice to difficult memories and emotions. Music therapy was later added, and the program has since expanded to the Fort Belvoir Community Hospital in

Virginia, where writing and visual art therapy are offered.

Oklahoma City showed the NEA and the nation how powerful the arts can be in terms of spiritual and physical rebirth. As Jones said, “There will never be a better example of how people respond to tragedy, to loss, to high emotion. What else can they use besides the arts?”