Starting Young

Wolf Trap National Park for the Performing Arts in Vienna, Virginia, boasts an honorable goal: to be a place where artists and enthusiasts can meet and revel in the power of performance. But even as Wolf Trap is dedicated to the performers and patrons of today, they are nurturing the artists and lifelong learners of tomorrow through arts education.

Wolf Trap established the Institute for Early Learning through the Arts in 1981 to bring professional artists to classrooms to work with children three to five years old in the disciplines of dance, drama, and music. Started through a grant from Head Start—a federal program that promotes “school readiness” for infants through kindergarteners from low-income families—the Institute addresses the achievement gap for economically disadvantaged children, which can emerge as early as 18 months when language skills of low-income children can begin to lag behind children from higher socioeconomic families.

“[Head Start] approached us to look at ways that we could use the performing arts to support children’s learning,” said Jennifer Cooper, the Institute’s director. This was not a shot in the dark. Research shows that while arts education can improve test scores and attendance for children from all backgrounds, the effects are particularly dramatic for low-income youth. The NEA’s 2012 report The Arts and Achievement in At-Risk Youth found that when engaged in the arts, socially and economically disadvantaged students outperformed their peers in terms of higher test scores, better grades, higher graduation rates, and increased college enrollment.

And yet, the arts are incredibly underutilized in the classroom, something the Institute seeks to change through partnerships between students, teachers, and artists, most often in Head Start communities. Although much focus has been on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and math) in education over the past decade, what has been overlooked is how arts-integrated techniques can improve STEM learning—not only are the arts not peripheral, they are a necessary part of the core learning process.

The Institute begins by training artists extensively in curriculum content, so they know what’s developmentally appropriate in math, literature, and science. For example, when the Institute began to focus on math in 2010, “Our artists came in and had a weeklong training in math content, so they would know the terminology, so they would know the concepts,” said Lori Phillips, associate director of professional development at Wolf Trap. “Then they applied their art form to get arts-integrated math.”

Artists are also trained in age-appropriate techniques within their own art form. Much of this understanding stems from a 1994 study by Wolf Trap on the impact of arts on preschoolers, an area that had not received much attention from researchers at the time. The NEA provided the seed money for Wolf Trap to undertake that study, and provided funding for a second study in 2009-2010. “It’s been foundational,” said Cooper of the second study. “We looked at the fundamentals of each art form, and developmentally appropriate ways to introduce each art form to young children.” For example, artists might suggest to teachers that music be broken down to tempo, pitch, and steady beat for their young students. For drama, teachers might focus on elements of character, setting, and voice.

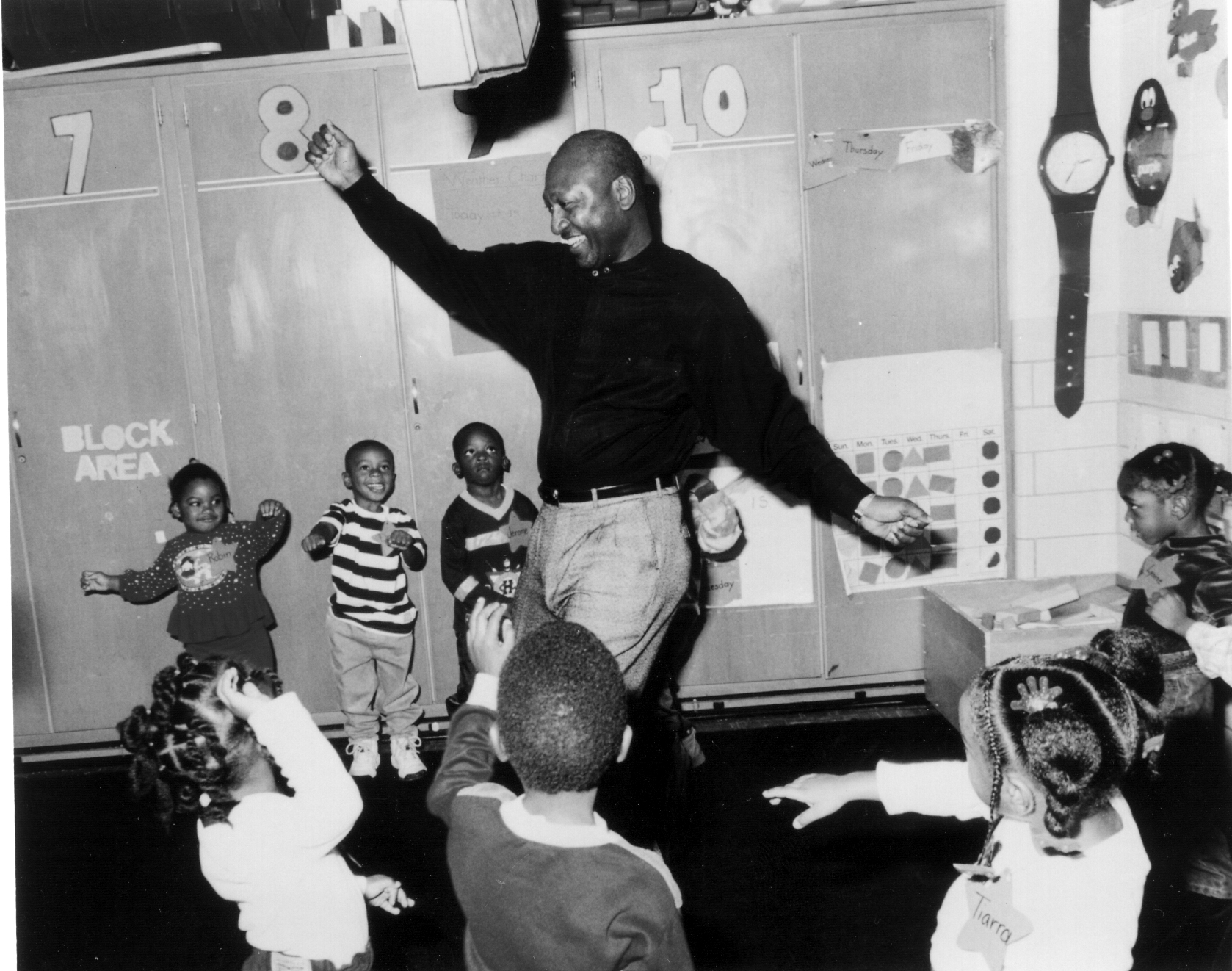

|

“Just like we work to share what’s appropriate in curriculum subjects to our teaching artists, we want to start with what’s appropriate for arts when we’re sharing with teachers,” said Cooper, noting that the results of that study have “been built into the fabric of what we’re doing.”

Following training at the Institute, artists then work in classrooms for one- or eight-week residencies, teaching children subject matter through the arts. At the same time, as Nicole Escudero, a childhood arts specialist at Wolf Trap, explained, the master artists offer teachers professional development so that they can learn to integrate the arts into their own lesson plans once the residencies have ended. Teachers can also access resources online at Wolf Trap’s website at education.wolftrap.org, which includes videos, audio clips, and lesson plans.

The Institute—which has been acknowledged for its achievements on CBS Sunday Morning, CNN World News, and BBC, and received a National Arts and Humanities Youth Program Award (previously Coming Up Taller Award) in 1996—continues to expand its educational programming. Certain initiatives focus on specific subjects, such as Wolf Trap’s Early STEM/Arts initiative, which recently received a grant from the U.S. Department of Education. Traditionally, STEM subjects have been considered the realm of men, a notion that is mirrored in classrooms, parenting, and teaching styles. But because of how early Wolf Trap's program is administered, it instills both young girls and boys with confidence in their ability to learn these disciplines before they see gender lines and subject bias. Early STEM/Arts has also shown to be beneficial to shy students, students who speak English as a second language, and children with learning disabilities.

Over the past 20 years, the NEA has continued to support Wolf Trap’s educational programming. The agency’s initial support helped the Institute attract corporate and other federal funding, allowing it to expand the program across the country. Although Wolf Trap residencies are limited to the Washington, DC, area, the Institute has 16 affiliates across the country, in addition to partnerships with school districts and educational organizations. “The growth nationally means reaching more children, it means reaching more teachers,” said Cooper. Every year, the program inspires and educates more than 50,000 children across the country.

|

But is it working? All signs point to yes. “We see it anecdotally, we see it when we’re in the classrooms,” said Cooper. Escudero shared a story about a boy with a learning disability that made it difficult for him to remember details from his lessons. But when his teacher brought in a puppet for storytelling, the student could remember every detail of the story the next day, and had enough confidence in his knowledge to ask questions enthusiastically.

Sandy Kozik, a dance teaching artist who participated in a Wolf Trap Institute program in Tennessee in 2001-02, said, “We already know the teacher/teaching artist bonds become stronger as both have to be a little more accountable when connecting to the standards. The possibilities for dancing and exploring wonderful children’s stories are endless.”

Although many such personal stories exist, Wolf Trap has fortified its argument for arts education through research. In a recent study, funded by the Department of Education, research showed that students who participated in the Institute’s Early STEM/Arts program scored higher in STEM subjects than non-Institute participants. This was especially true for math, where the Institute group scored eight percentile points higher than their peers. (Early math skills, it should be noted, are one of the strongest indicators of academic success later in life.) On a visit to Wolf Trap’s Brightwood campus in Washington, DC, Secretary of Education Arne Duncan gave the program high marks for its use of performing arts to reinforce STEM concepts.

Another study, published in 2006, found that preschool children who participated in a Wolf Trap Institute residency showed significant improvement across six different areas: initiative, social relations, creative representation, language and literacy, logic and mathematics, and movement and music.

The NEA’s goal of having the arts be part of everyone’s education, to develop America’s next generation of creative and innovative thinkers, is being realized at Wolf Trap. The impact, anecdotally and statistically, is profound. As Cooper said, “We’re building both the love of learning in children at the same time that they’re getting introduced to the performing arts.”