Telling Stories with Light

Listen to a theater audience leaving a performance of, say, Lin-Manuel Miranda’s Hamilton or Katori Hall’s The Blood Quilt and you’ll hear them talk about a lot of things: the story itself, how much they liked (or didn’t like) the costumes, whether the music was as good live as it is on the official cast album, or how they wish they owned some piece of furniture from the set. What you probably won’t hear them talk about is the production’s lighting design. While most people get excited for the moment that the house lights dim and the stage lights start to shimmer, very few can articulate how the overall lighting design affected their experience of the show.

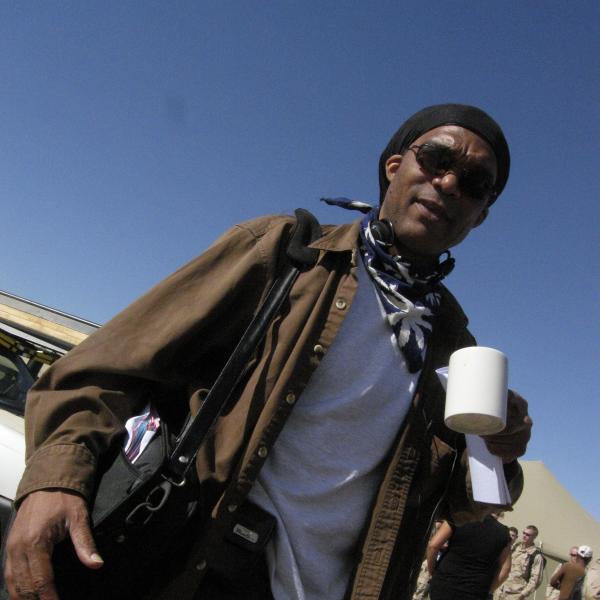

This is no surprise to veteran lighting designer Jeanette Oi-Suk Yew who’s long made her peace with the fact that audiences rarely have an idea of what her work entails—or even that her job exists. “I’ve been to many different gatherings with people who are not necessarily in the theater. [When I say I work in theater,] they’ll say, ‘Oh, are you an actor? Are you a director? Are you a playwright?’ And then they kind of stop there.”

She observed that part of the difficulty in understanding what she does is that the work isn’t tangible. “If I said that I make costumes, they’d go, ‘Oh, I get it. That’s what they’re wearing.’ Or if I said that I made the set, people get it. But with lighting design, it’s sort of like, ‘Oh well, aren’t you just turning lights on?’”

|

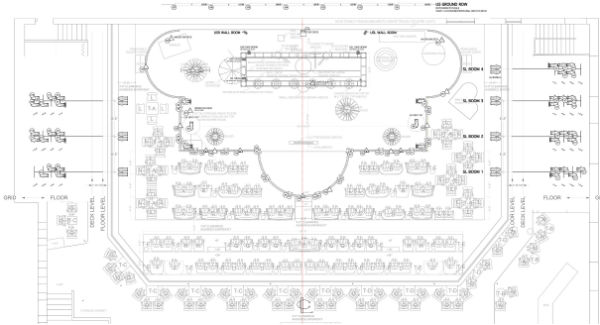

For a recent project, for example, Yew had to imagine the world of a cemetery waiting room. She explained, “The core of the story was about two people suffering a lot of grief and trying to make a connection with each other in a very unusual and sterilized space. So that is what I’m thinking about a lot as a designer. What is this space? What is this environment that this story is unfolding within? [My thinking] is very architectural-based in some ways.”

Lighting design is in fact equal parts art and science and involves a lot more than just turning the lights on and off. As Yew described her work, “I’m building the basis of what this light feels like in this space.” As a lighting designer, Yew has to understand not just the physical properties of light, but its emotional properties. She also has to understand how light works given a particular set of constraints, such as the dimensions of the set or the palette of the costumes. As she works, Yew ponders questions such as whether the space should feel environmental or magical. Does it need to have a lot of contrasts? Does it need to feel very emotional?

In the early days of what we think of as the modern theater, theatrical lighting was rudimentary at best, comprising candles and then gaslights. The history of theater—and other forms of performance such as dance—is rife with stories of performers setting themselves on fire by getting too close to the footlights. By the 1900s, with the advent of the electric light bulb, performances could include specific illumination—such as spotlights—as well as general lighting. Still, lighting effects were usually the purview of the set designer. It wasn’t until the 1930s that lighting design evolved into its own specialty.

While Yew bears ultimate responsibility for the lighting design, her work is rooted in collaboration. As Yew related, the design process starts with a series of conversations with the production’s director and the entire design team about “what is this world that we’re trying to create so that this story can exist.”

After getting a handle on what a particular work is about, the next step is for the director and design team to discuss possible challenges. “Every single piece that you do, there are some things that you are challenged by, [such as] some impossible stage direction or a limited budget,” she explained.

Yew also attends rehearsals throughout her design process. “Because lighting design is a movement-based design and because we are dealing with a time-based element, the movement of how people react in space becomes very important,” she said.

|

The final design isn’t executed until technical rehearsals, which start a few days before the performance’s first public showing. Few shows rehearse in the space in which they’ll be performed, and when the space becomes available, sets must first be built and finalized, and performers must acclimate themselves to those sets. It is only then that lights are hung and positioned, color filters—known as gels—are installed, cues are set, and all the physical components of the lighting design are executed.

Yew calls lighting design “the last jigsaw puzzle piece because we don’t get to try anything earlier. The responsibility becomes about, ‘Okay, am I creating a total picture onstage?’ There’s nothing I can try out at all until I am in tech because we just don’t have the resources to set up lighting or be in the theater early. So all of my work is completely public. It has to be done with everybody in the room.”

This public aspect of her work is particularly challenging as it demands not only exquisite attention to detail but a fair amount of multitasking. Yew said, “[It means] being able to really keep track of a lot of things thrown at you at the same time, like being able to hear the director and watch what’s on stage and keeping notes in your mind and keeping track of time. I guess that’s my superpower: being able to store all that information in an organized way and in a very short amount of time.”

Like many theater professionals, Yew is a multi-hyphenate artist. In addition to her lighting design work, she also works in video and puppetry. Both art forms appeal to her because, like lighting design, they each have an ephemeral quality, albeit with an added element of concreteness that she embraces. Her exploration of these other forms also deeply informs her lighting work. Making videos allows her to further ponder the qualities of light from a different source, while working in puppetry helps her understand the creative process of a production as a whole. “With puppetry, similar to lighting, it forces me to think about the totality of the design, because as a puppeteer you think from beginning to end when you create work,” Yew explained. “You are the playwright, you are the costume designer, you are the set designer, you are the lighting designer.”

|

This ability to see multiple viewpoints also allows Yew to be clear-eyed about issues she sees in the theater field at large, such as the scarcity of women designers and designers of color within larger regional theaters or on Broadway. “I think there’s a little bit of a glass ceiling,” said Yew of working at that level. “My experience has been if I’m working in a non-regional theater or an off-off-Broadway theater, I encounter a lot more women designers and women behind the scenes, either the stage manager or dramaturge, or [positions] like that.”

She believes the field needs more role models who identify as women or who are people of color so that a more diverse pool of people will be attracted to work in it. “If people can see that this costume designer is from Japan or from the Dominican Republic, then people will see that this is possible.” Yew cites economics as another barrier to having a more diverse workforce in theater. “As a designer it’s hard to make a living. If you’re coming from an already economically challenging background, it’s just hard to make that decision to go into the field.” She also said that attitudes need to change in terms of identifying people by the function they perform instead of what they look like. “I know that when I walk into a room, people look at me as an Asian woman lighting designer. They’re not looking at me as a lighting designer.”

Despite these challenges, Yew remains optimistic about her work and is game to take on new projects. Although she likes the ease of collaborating with colleagues with whom she’s previously worked, she particularly likes “projects that I don’t know anything about to challenge myself,” she said. “It’s also about practice for me.” She’s especially drawn to new works “because there’s a whole discovery process. I look at every opportunity as a way to grow and learn more.”