Creative Approaches to Problem-Solving

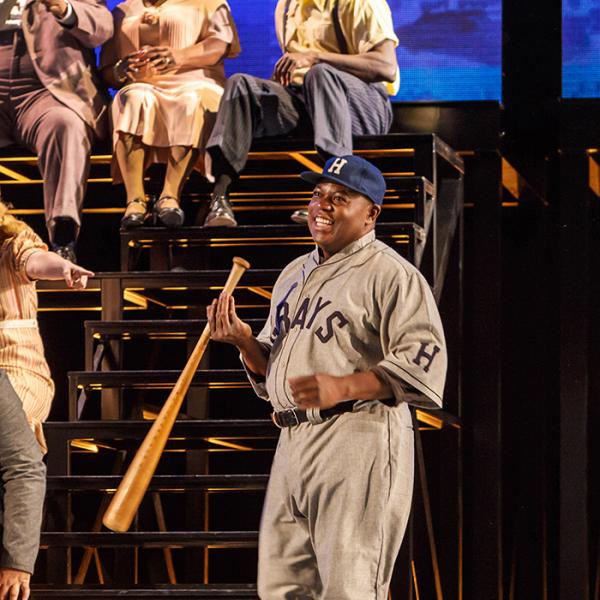

NEA Chairman Jane Chu, on a visit to the Appalachian Artisan Center in April 2015, examines some of the dulcimers that originated in Knott County, Kentucky, with Doug Naselroad, who manages the luthiery school at the center. Photo by NEA staff

Located in the state’s eastern Appalachian region, Hindman, Kentucky, has seen its share of hardship in recent decades. The collapse of the coal industry left behind rampant unemployment, and the nation’s opiate epidemic has hit Appalachia particularly hard—in 2015, Kentucky had the third-highest rate of overdose- related deaths. Between these two issues, “there’s hardly a family in Knott County that has not been affected,” Jessica Evans said.

But as director of Hindman’s Appalachian Artisan Center, Evans has seen how the arts can provide a way forward for the town’s 750 residents, the community, and the region as a whole. Here, in a building where stacks of wood wait to be turned into dulcimers, where sparks fly from the blacksmith’s belt grinder, and where colorful canvases line the walls, artists are creating a balm for Hindman’s struggles.

The organization was founded in 2001 through former Governor Paul Patton’s Community Development Initiative, which also established the nearby Kentucky School of Craft. The two organizations drew on the region’s rich cultural heritage, which has been shaped by generations of basketmakers, potters, blacksmiths, and luthiers. By training artists at the school, and then offering them further professional development, studio space, and platforms to promote their work at the Appalachian Artisan Center, it was hoped that a new economy based on the arts and cultural tourism would emerge.

And bit by bit, it has. Today, the Artisan Center offers luthiery, pottery, and blacksmithing workshops and apprenticeships, as well as incubator studios that are open to artists working with any medium. The center draws artists from 30 counties in eastern Kentucky, whose work is featured through an online and brick- and-mortar store, exhibitions and performances, and events such as the center’s Old-Fashioned Christmas celebration and the annual Hindman Dulcimer Homecoming Festival. In 2016, the center opened a new gallery and studio space, complete with a rooftop garden.

This momentum has been propelled in part by the Kentucky Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts. More than half of the Artisan Center’s income comes from grants, and in 2016, the Kentucky Arts Council and the National Endowment for the Arts provided a total of $79,000. Operational grants from the Kentucky Arts Council have “had a hand in everything,” said Evans, while the council’s marketing platforms and invitations to statewide events such as Kentucky Crafted have helped vault the Artisan Center out of Appalachia and onto the state’s main stage.

|

On the national level, the NEA has awarded $170,000 to the center through various grant programs since 2011, which have funded residencies, apprenticeships, and the expansion of the center’s luthiery school. The school, which is managed by master luthier Doug Naselroad, is a central piece of the Artisan Center’s activities, and will eventually include a program to help trained luthiers find work through the Troublesome Creek Stringed Instrument Company.

It is clear that these investments by the NEA and Kentucky Arts Council have paid off. As its facilities and programs have grown, the Artisan Center has given people “the ability to provide for their families or supplement their income with their own craft and their own handwork,” said Evans. It has also started to put Hindman on the map as a tourist destination: in 2015, the Appalachian Artisan Center drew 10,000 visitors, and artists saw a 67 percent growth in retail sales, with customers hailing from 21 different states.

“We’re able to see real proof that through embracing Kentucky’s traditions, our artists are providing innovation that leads the state,” said Lydia Bailey Brown, executive director of the Kentucky Arts Council. She noted that Hindman has become a primary stop for cultural tourists, particularly those who might be interested in the mountain dulcimer, a unique, hourglass-shaped instrument that originated in Knott County at the hands of Uncle Ed Thomas in the 19th century.

But economic momentum is just one facet of the Artisan Center’s impact—equally meaningful has been the deeper social and emotional change. “I truly believe that one of the things that the Artisan Center can offer people is hope for their own future—the gift of a larger life,” said Evans. “There are a lot of people for whom the Artisan Center is the reason that they get out of bed and come to town.” She has seen people recovering from addiction “latch on to crafts as a way to better themselves as an alternative to any of the other choices they could be making.” One paramedic who participates in the center’s blacksmithing apprentice program has said the rhythmic pounding helps mitigate the high-stress atmosphere of his job, where he sees overdoses on a daily basis.

Indeed, returning to the region’s creative roots has been a source of healing for the community at large, as it has refocused residents’ collective sense of identity from one of hardship to one of artistic innovation, cultural tradition, and local talent. “When they take that identity and share the story of it not only within the community but beyond, it becomes a symbol and something that makes them proud of their region,” said Mark Brown, director of folk and traditional arts at the Kentucky Arts Council.

Part of this pride has stemmed from the Artisan Center’s efforts to expand awareness of Hindman’s cultural history, in addition to enhancing artistic skill. In 2014, for example, the Appalachian Artisan Center hosted a six-week Community Scholars Program led by the Kentucky Arts Council. Twenty Hindman residents—including Evans and several other Artisan Center staff—took part in the training, which taught participants how to document and archive local folk traditions. “After the course is complete, you have 20 community members that can then take that knowledge, go into communities, record the folk songs that their uncle learned from their grandfather, or document a family member talking about the craft their grandmother taught them, or how they learned quilting,” said Evans.

|

The certification coincided with the Artisan Center’s Dulcimer Project, which received $75,000 through NEA’s Our Town creative placemaking program. In addition to workshops, the Dulcimer Project involved documenting oral histories surrounding the homegrown instrument. Artisan Center staff were able to take the skills they learned from the Community Scholars Certification Program and capture Appalachia’s rich legacy regarding the instrument, creating an archive of both global historical signi cance and intense local pride. The Hindman Dulcimer Homecoming Festival, which was first launched through the Dulcimer Project, will see its fourth iteration this November.

It’s an apt example of how the Appalachian Artisan Center has helped the region rediscover what’s been there all along: centuries of creativity and ingenuity, which Evans believes will serve the town well as it continues to recover. “At the core of the arts is creativity and a willingness to look outside the box,” said Evans. “We are in a tough spot in Appalachia. You need creative approaches to these problems to solve them, because all the traditional methods of problem-solving have been tried, and we haven’t seen significant results. I do believe the arts are important in that regard.”