Out of the Ballpark

Maine is known for many things: lobsters, stunning vistas, lots of snow, lots of moose, and as the birthplace of Henry Wadsworth Longfellow and Stephen King, to name just a few. Opera, however, isn’t one of them. But Portland Ovations is changing that. In 2014, with the assistance of the National Endowment for the Arts and the Maine Arts Commission, Portland Ovations commissioned a local music professor to complete an opera on a decidedly non-operatic topic: Josh Gibson, a member of baseball’s Negro Leagues. The staged concert of The Summer King caught the attention of the Pittsburgh Opera, which eventually planned a full-scale production of the opera as its first world premiere in its 78-year history. How did this all happen?

There is only one professional opera company in the mostly rural state of Maine, and it produces one fully staged opera each summer. So the development and production of a new opera would require the collaboration of a number of different organizations.

In the early 2000s, University of Southern Maine (USM) music professor Dan Sonenberg decided to combine his love of baseball with his professional knowledge of music into something new: an opera. “I was actually interested in the Negro Leagues, and even in particular Josh Gibson, before I was interested in opera,” said Sonenberg. “I didn’t really get interested in opera until I got to college. When I got into opera, somewhere along the line those two ideas just kind of got married in my mind.”

With support from American Opera Projects (AOP), a New York-based nonprofit that develops new works of opera by established and emerging American artists, Sonenberg was able to begin developing the piece as part of their Composers & the Voice Workshop Series, a program that pairs professional singers with composers to provide experience writing for the opera stage. From that start, he worked on the libretto with poet Dan Nester, who eventually dropped out of the project in 2004. Sonenberg continued working on the piece, composing the music and revising the libretto, on and off over the next few years.

The story Sonenberg developed focuses on Gibson, a great athlete who played for Pittsburgh’s Homestead Grays in the Negro Leagues and once hit a ball completely out of Yankee Stadium. The story chronicles his early success (some had said he was better than Babe Ruth), the discrimination that kept him from playing in the major leagues, the death of his wife in childbirth, a stint playing baseball in Mexico, and his tragic early death at 35 from a brain tumor shortly before Jackie Robinson integrated baseball by joining the Brooklyn Dodgers.

The music Sonenberg composed is as eclectic (for opera) as his subject matter. “You’re telling a story that takes place in Pittsburgh, where the Crawford Grill was a central location of the story, and that was a very important jazz destination in the country.” So Sonenberg included saxophone and drums as integral parts of the orchestration. For scenes that take place in Mexico, he borrowed mariachi motifs to capture the spirit of the environment.

Sonenberg found himself at a crossroads with his opera—what to do with it next? That’s where the Maine Arts Commission—which provides grants to support the arts in the state—first stepped in. In 2012, the Arts Commission provided Sonenberg a grant of $1,500 to support his burgeoning opera. “He wanted to create professional marketing materials so that he could market the opera to professional opera companies,” said Julie Richard, Maine Arts Commission’s executive director.

“Nobody knows what an opera sounds like unless they have a really good recording in front of them,” Sonenberg said. “And a really good recording is just tremendously expensive. I did a piano-vocal plus mariachi ensemble of a scene in Mexico from the opera. The Maine Arts Commission has been hugely supportive to me on this project.”

|

It was about this time that Aimée Petrin of Portland Ovations came into the picture. Portland Ovations, a nonprofit presenting organization, had worked with Sonenberg over the years, bringing him in as one of their go-to scholars for pre-performance lectures. When Petrin heard that Sonenberg had a major project that he had been working on for years, she was intrigued and had a meeting with him. “We started to talk [about] what it would take for him to be able to finish it and then for us to be able to mount it.”

Portland Ovations made a commitment to not just commission the piece, but to produce it as well. “This is the first time that we have commissioned something that we have been instrumental in creating from the ground up,” said Petrin. “We knew whatever we did, it would have to be a concert [without sets or costumes] just because even as an organization committed to doing this, we don’t have our own venue. We don’t have a scene shop or a costume shop.”

Once again, the Maine Arts Commission made a contribution to the project, providing a grant for $6,000. “We used that funding to pay for the professional musicians in the orchestra and to do some honoraria for the collaborators who were Maine-based,” said Petrin. “We’re still hearing from musicians that participated in it that this was one of the most exciting, thrilling, and important experiences of their professional life.”

Portland Ovations ended up using part of a $40,000 NEA grant for their 2013-14 season toward The Summer King presentation, which would be the season finale. In 2014, USM received an NEA grant of $15,000 to support the artist fees for the singers. “Obviously, we didn’t want to do this and not pay the artists, so having those two funding pieces from the NEA made it happen,” said Petrin. “We were able to breathe. We were able to say that we can do this.” In all, Portland Ovations raised $75,000 to stage the concert.

In Sonenberg’s opinion, the NEA grant to the university “ended up being a great thing, because it pulled my university on board as collaborators in the process, which they took seriously. Once you get an NEA grant, then it’s a serious project.” The university held a symposium on the opera and helped promote the concert.

AOP continued to be involved in the project as well, pitching The Summer King to Opera America’s New Works Forum, which involved libretto readings and orchestral performances of pieces of the opera months before the Portland event. Christopher Hahn, general director of Pittsburgh Opera, was in attendance at the forum, and was interested enough to attend the Portland concert of the full score. AOP also assisted with the audition process for the lead singers and in bringing Steven Osgood, assistant conductor of the Metropolitan Opera in New York, on board as musical director.

|

The full-length concert—which included the Boy Singers of Maine, the Maine-based Vox Nova Chamber Choir (of which Maine Arts Commission’s Julie Richard happened to be a member), and a 16-piece local orchestra—drew close to a thousand audience members, including representatives of various professional opera companies to see if it was something they wanted to mount as part of their seasons. Soon after the concert, Pittsburgh Opera invited Sonenberg to the city to discuss a possible production of the opera.

“I knew that, for Pittsburgh Opera’s first world premiere, we needed to reach out and embrace this whole community with a story that resonated deeply,” said Hahn. “Josh Gibson has a high level of name recognition, especially here in sports-obsessed Pittsburgh. And what more fitting subject could we find for our first-ever world premiere than a native son of athletic distinction who died tragically young?”

The opera would need significant revisions before the premiere, but the Portland performance gave Sonenberg the opportunity to see the opera as a whole, with singers, chorus, and orchestra. “Just to hear it performed from start to finish,” Sonenberg noted, “and to suddenly get this influx of feedback and responses to the story, to the character development—I took a lot of notes on people’s responses to the opera. There would be no revision process if that hadn’t happened.”

|

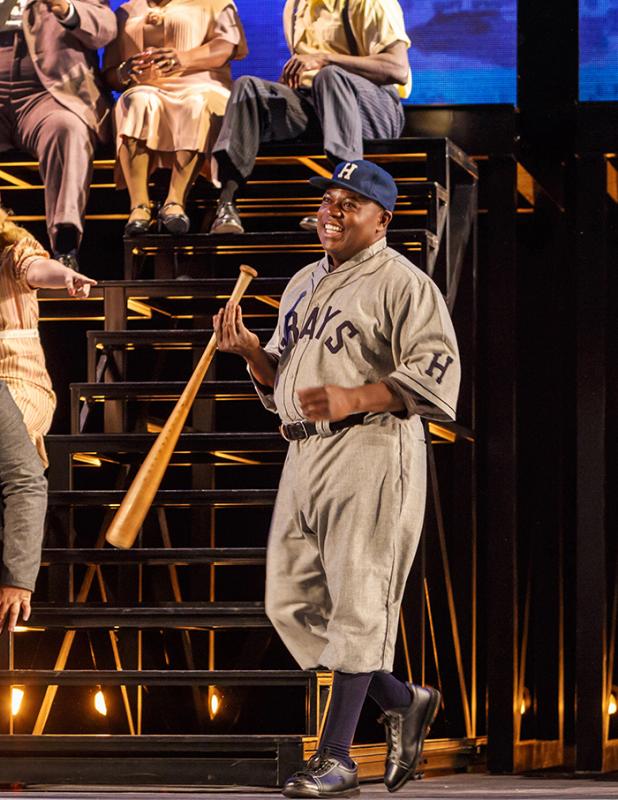

As part of the Pittsburgh Opera’s promotion, they held free community events, partnering with the Josh Gibson Foundation to hold discussions about Gibson and baseball’s Negro League in relation to the opera. By all accounts, the premiere was a success, selling out Pittsburgh’s Benedum Center for the Arts, featuring Alfred Walker as Gibson, Jacqueline Echols as his wife Helen, and Denyce Graves as Gibson’s girlfriend Grace. A new production is scheduled next year in Detroit with the Michigan Opera Theatre.

The small investments from the National Endowment for the Arts and from the Maine Arts Commission had a large result: enriching the community of Portland with the presentation of a new operatic work, leading to a full-scale production in Pittsburgh, which enriched that community as well (and with a $1 million-plus production, supported by an NEA grant, it was also a boon to the local arts scene and economy). Just as important, their investments to the collaboration of American Opera Projects, the University of Southern Maine, and Portland Ovations led to a new work in the American opera canon that celebrates a significant chapter from African-American history—which enriches all of us.

“You have to be willing to make the commitment to the artist and the process,” said Petrin. “If you’re not willing to do that, then things like this don’t happen and the world misses out on great works.”