An Invitation to Create

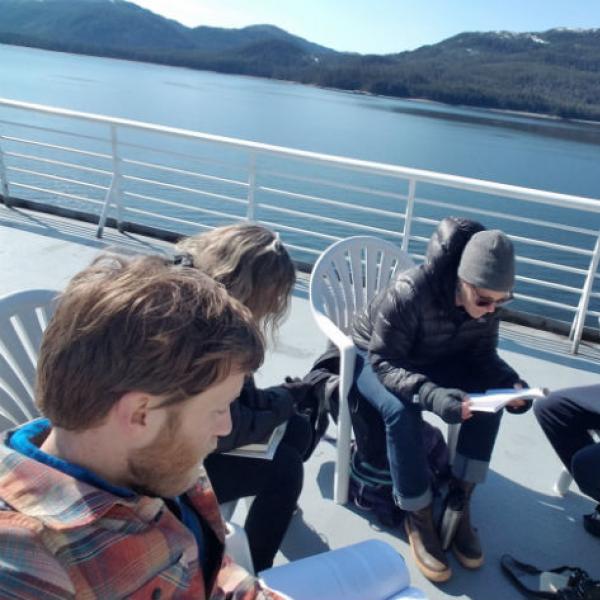

BodyVox’s Eric Skinner leads a dance workshop at Avanti High School in Olympia, Washington. Photo courtesy of the Washington Center for the Performing Arts

If you walk by Chris Sogn’s science class during the Earth sciences unit at Avanti High School in Olympia, Washington, you’ll be greeted not only by wide-eyed, engaged students, but also by a hallway-turned-cavern, complete with stalagmites and stalactites. Venture down to Todd Thedell’s math class and you might be struck by the student-made posters and fractals adorning every possible surface, as well as the ukuleles that the musical math teacher introduced into the robust curriculum. And every October, John Hamby’s English students create a haunted house during their study of macabre literature, and have an opportunity to share their own stories on the stage.

Avanti High School’s arts-integrated curriculum reflects the school’s capacity for thinking outside traditional teaching norms in order to better fit the unique needs of its students. Upwards of 97 percent of Avanti students have an anxiety disorder, and the school community of 150 endured 24 suicide attempts last year.

But the arts have been shown to have positive emotional effects. For example, they have been shown to reduce depression and anxiety, and can help people confront and process difficult emotions like frustration, grief, and anger. In conjunction with traditional academic subjects, Avanti’s creative curriculum aims to create spaces that promote healing, boost confidence, and cultivate success.

So when Avanti guidance counselor Claire McGibbon was approached by Jill Barnes, executive director of the Washington Center for the Performing Arts, about a programming partnership, it seemed tailor-made for Avanti’s uniquely gifted student population and arts-rich curriculum. Although McGibbon had previously served on the education committee of the Washington Center, which is just a ten-minute walk down the road from Avanti, it would be the first time the two entities officially collaborated.

Once the Washington Center and Avanti teamed up for the venture, Barnes called on BodyVox, a Portland-based dance troupe with whom the organization has cultivated a performance-based relationship, as well as Black Violin, a Florida-based hip-hop and classical music act. With the support of a $10,000 Challenge America grant from the NEA, BodyVox worked with Avanti students during a three-month residency last winter, with culminating performances by both BodyVox and Black Violin. Challenge America grants are intended to reach underserved populations, such as those with mental health challenges. Between 2004 and 2016, $36.2 million in Challenge America grants have been awarded to organizations with the express intent of bringing the arts to places and communities where they are traditionally lacking.

|

For this particular project, all dance workshops were voluntary; both Barnes and McGibbon agreed that the program would work best if students self-selected to participate. Still, they were both surprised by the capacity for the dance classes to overcome many of the students’ inhibitions.

“There were some that were standoffish, or just observing and not participating straight away with the first workshop,” said Barnes. “But it was not long before they jumped in. That speaks to Eric [Skinner], the dancer who was facilitating it—he’s very approachable and accessible. But it also speaks to the nature of the school culture at Avanti.”

McGibbon stressed the extent to which dance was able to overcome neurological barriers that could not be traversed verbally in a traditional academic setting. By connecting their brains to making a particular movement, the students were able to relate to dancing on a fundamental level.

McGibbon described it as a “playful, childlike connection. Non-judgmental. One of the students was autistic, and he’s like, ‘I just can’t believe it didn’t matter! I wasn’t judged! It didn’t matter about my body! I just got to move it. And I didn’t care whether I was moving the same as everybody else.’”

“I would just like to encourage anybody that is nervous about dancing or thinks that they’re too fat to be able to be graceful, just dance,” said Spencer Beadle, an Avanti student who was part of a video the Washington Center made about the workshop series.

Personal experience and becoming comfortable in their own bodies was central to the dance workshops. BodyVox’s hands-on approach also fostered the type of environment in which Avanti students could thrive.

“Ninety percent of our population [has a] primarily kinesthetic learning style,” said McGibbon, who also has a background in brain theory and was named 2015-16 Olympia School District Teacher of the Year. “It’s [based on] experience, and the arts are essential to the experience. In that experience, there’s expression, and in that expression there’s personal development, there’s authorship of life. And there’s creation. It’s that invitation to create and go beyond the sum of your parts.”

She noted how dramatic this act of creation can be for Avanti students. “When you have kids who have left traditional high school because they can’t express themselves perform[ing] publicly and feeling confident about it? That’s a miracle!”

Black Violin’s performance continued the trend of unforgettable experiences that the Washington Center provided for Avanti’s students. The hip-hop/classical fusion duo is comprised of Kevin Sylvester and Wilner Baptiste, who go by the stage names Kev Marcus and Wil B. They performed a show that was, all at once, inspiring, educational, and wildly entertaining.

Their style pushed the boundaries of conventional musical performance, a methodology that clearly resonated with the students.

Observing from the back of the theater, Barnes noted that, “Black Violin shared an amazing message to the students of, ‘We learned how to play, and then we made it our own.’ It was basically, ‘Trust yourself, follow your own path, and you can do whatever you want.’ They were really encouraging that way.”

It was clear that Black Violin’s message had a significant impact on those in attendance. For example, on the day of the concert, McGibbon found one of her students, a fifth-year senior on the verge of completing his last credits, hanging back. At this point the public evening show was long sold-out and her student, also a musician, didn’t have a ticket. So McGibbon gave him her ticket instead. “He came back in tears. It gave him the motivation to finish [school],” she said. “To sit and look at him and have him say, ‘Thank you. This changed my awareness and my life and it has engaged me on a level that I know I can put what’s inside me in motion.’ It was one of those profound moments.” The student graduated this spring and will begin at Evergreen State College in Olympia this fall, with full funding.

The NEA’s Challenge America grant provided the Washington Center and Avanti the opportunity to enhance students’ interaction with the arts. For McGibbon, the reactions of her students demonstrated her belief that the arts can unlock their potential and provide the answers that cannot be explained in words. “I’m deeply grateful for these kids who wouldn’t have had this opportunity,” she said of the workshops and performances. “[They’ll] have something inside them that they’ll come back to because of the experience. This is what the arts are about!”

Elijah Levine was an intern in the NEA Office of Public Affairs in summer 2017.