Stitching Lives Together

How can we expect a woman to navigate her life in 90 days?” asked Deborah Frazier, executive director of Blues City Cultural Center, a Memphis nonprofit she co-founded with her husband Levi in 1979. She was referring to the maximum stay of many of the nation’s emergency homeless shelters, which are designed to offer short-term housing for women who find themselves unexpectedly homeless. “You have to find a job. You have to find a place to live. You have to put your children in school—all those things in 90 days.”

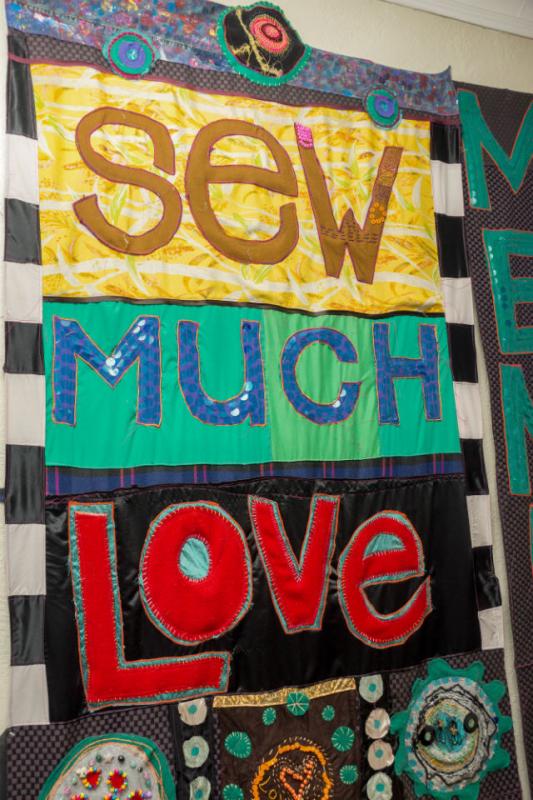

To help address the issue, three years ago Blues City Cultural Center launched the program Sew Much Love, which advances the organization’s mission to empower lives through the arts, particularly among communities that have been traditionally marginalized. Memphis has a homeless population of roughly 1,800 individuals, 500 of whom are women at any given time.

In partnership with the nearby Salvation Army and Missionaries of Charity shelters, Sew Much Love engages multidisciplinary artists to guide homeless women through creative projects such as writing poetry, making masks, and sewing dolls, quilts, and costumes. The program also provides a stipend and daily meal, which together create a safe, supportive refuge during daytime hours when both shelters require residents to vacate the premises. The program received its first NEA grant this year.

At its most basic, Sew Much Love allows women to momentarily escape their burdens, and enjoy a few hours when they are free to “dream and play and create,” said Frazier, a release that she believes is a necessity. But its deeper, longer-term goals are to help women transform creatively, emotionally, and even economically, as they learn about the possibilities of creative entrepreneurship.

|

It is a journey that the women undertake together. “One of the things we try to establish in the beginning is that this is a community, much like times of old when women created sewing circles and quilting bees,” said poet Carolyn Matthews, project coordinator for Sew Much Love. “Usually we’ll open up in the morning and ask, ‘How are you feeling? Do you want to check in? Do you need anything from us? How can we serve you?’”

For women who have been turned out by husbands or families, who have escaped abusive relationships or are dealing with the lonely struggle of addiction or mental health issues, even simple questions such as these imply a support system to which they might be unaccustomed. Positive feedback is constant, and no judgments are passed. Sew Much Love also provides occasional cooking lessons, visits from life coaches, and help with obtaining proper identification and establishing bank accounts, all of which deepens this sense of support.

As they accept Sew Much Love as a safe space, women often find themselves revealing their emotions and experiences through their art. For example, when Sew Much Love participants make dolls, they are encouraged to give them a name. “So you come up with a name like Nameless Faceless,” said Matthews. “That’s powerful for a person to be able to verbalize that the reason they’re naming their doll this is because this is the way they feel. They feel invisible. To get to the point where you can release something that vulnerable into the world—it’s freeing. You feel safe enough to do that. You are releasing that in a group of people who understand that, and are willing to hear you.”

Frazier agreed. “A lot of what we do is just have [women] recognize that what they say has merit and is important.”

Carol, 52, a program participant, said this camaraderie is part of the reason she has participated in Sew Much Love for the past year, after finding herself homeless following a divorce. “Knowing that there’s somebody you can become friends with and talk to, that has your back and has gone through the same kinds of circumstances you have—it’s a very enjoyable environment,” she said.

Matthews is careful to note, however, that while the program might provide a sense of healing, it is not designed to be art therapy. But even so, gentle questioning about projects women have made provides plenty of opportunities for them to engage with the motivations behind their creative choices. “It’s frivolous and irresponsible to have art-making without taking advantage of meaning-making as well,” she said. “Meaning-making itself is cathartic because you’re providing a venue to release expression verbally and creatively about what’s going on inside you. They have an opportunity—if they want it—to express that and build through it.”

By identifying their patterns of negative self-talk, possibly for the first time, women begin the process of learning how to break the cycle. Paired with the discovery of their own creative powers, they see something in themselves that they might not have before: value.

“[Sew Much Love] makes you feel like you have some worth—that I do have some worth in the world,” said Carol.

|

Matthews said Carol’s experience is not uncommon among Sew Much Love participants. “Art-making is almost unparalleled in helping people see they have something of value in themselves,” said Matthews. “Making art is a place of reflection. It’s intentional. It’s organic at the same time. It’s spontaneous. It’s a whole process that brings [these women] to life, enlivens them, and opens them to new possibilities.”

One of these new possibilities that the program introduces is economic independence and financial stability. Annual exhibitions offer showcases where visitors can purchase artwork made by program participants, which not only provides women with income but validates their talent and creativity. In August, Sew Much Love also ran a two-week pop-up shop on North Main Street thanks to funding from the Downtown Memphis Commission. Before the shop opened, women worked with retail professionals to learn about customer service and sales, providing valuable experience as they prepare to enter or re-enter the job market. Frazier also dreams of one day establishing a drop-in sewing enterprise, where Sew Much Love participants could make on-the-spot fabric repairs or alterations for clients.

These public-facing events also introduce the wider Memphis community to the individual stories that make up Memphis’s homeless population—a population that is generally thought of as an abstract problem rather than in personal terms. “There’s something about being in close proximity and hearing a person’s story firsthand that impacts [people] in such a way that it will cause them to think twice about their preconceived notions,” said Matthews.

But Frazier stressed that changing public perception is more of a byproduct than a goal; the main priority has always been to change women’s perceptions of themselves. She noted that women are often too ashamed or afraid to come to presentations or receptions at Blues City Cultural Center’s offices where members of the general public might be. But last April, with support from the NEA, the women created costumes and puppets that they displayed in a parade and fashion show as part of the Taste of Memphis festival. “When we said ‘fashion show,’ everything changed,” said Frazier. “They became models. So it’s not so much that the community has a different idea of who they are. But they have a different idea of who they are.”

In a way, said Frazier, the emotional, social, and financial changes that Sew Much Love participants undergo are not so different from the creative process itself. “We have a lot of materials that have been donated to us—things that basically have been thrown away,” said Frazier. “What we’re saying is we’re repurposing not only [these materials], but we’re repurposing our lives.”