Toward a More Creative Future

Southeast Alaska comprises 600 miles of coastline and hundreds of islands collectively known as the Alexander Archipelago. Given its terrain of dense forests and mountains, Southeast Alaska, which includes Sitka, Ketchikan, and Alaska’s capital city of Juneau, finds itself geographically isolated in a state that’s already geographically isolated from the U.S. mainland. Despite the relative isolation of the region’s many small communities—most are reachable only by air or water—they share common concerns with the larger world, such as domestic violence, drug and substance abuse, gentrification, and the environment, among other issues.

These Alaskan communities also have something else of significance in common: the Alaska Marine Highway, a series of waterways stretching 3,500 miles and traversed by a fleet of ferries. The ferry system regularly transports tourists, cars, and cargo to various points in Southeast Alaska. Thanks to the ingenuity of Sitka-based arts organization Island Institute, the Alaska Marine Highway is now also unique in another way: each spring it boasts a group of artists participating in Tidelines Journey, a unique, seafaring artist residency that offers artists and residents of the region a way to think about and discuss the area’s pressing questions.

The idea of a nomadic residency first occurred to Island Institute Executive Director Peter Bradley during his initial visit to the Alliance of Artist Communities conference in October 2015. As he learned about the varied shapes and forms an artist residency could take, he realized that the Marine Highway offered an opportunity to create a roving residency that was different from the residency experience the institute already offered for visiting artists.

|

For the new residency he envisioned, Bradley wanted to do more than provide idyllic workspace for artists. He also wanted to create an environment that fostered conversation, and created what he called “a reciprocal learning opportunity” not only among the artists, but also between the artists and the region’s residents.

“There are all these very fascinating communities in Southeast Alaska of people that have this incredible eloquence about their sense of belonging... people that I thought have a lot to teach the artists but also who have a lot of curiosity for what the artists may bring,” he explained.

The Island Institute has a long history of creating just these types of creative collisions. Established in 1984, its original mission was to facilitate conversation around ideas of community, such as how to foster shared values or live symbiotically with the natural world. In recent years, the institute’s goals have become more reflective of the local region, with a focus on engaging the area’s residents in communal storytelling about their lives in Southeast Alaska as well as around significant events, such as a devastating landslide that struck the area in August 2015. The organization’s offerings also include youth workshops, a bookmaking studio, and traditional, fixed-location artist residencies.

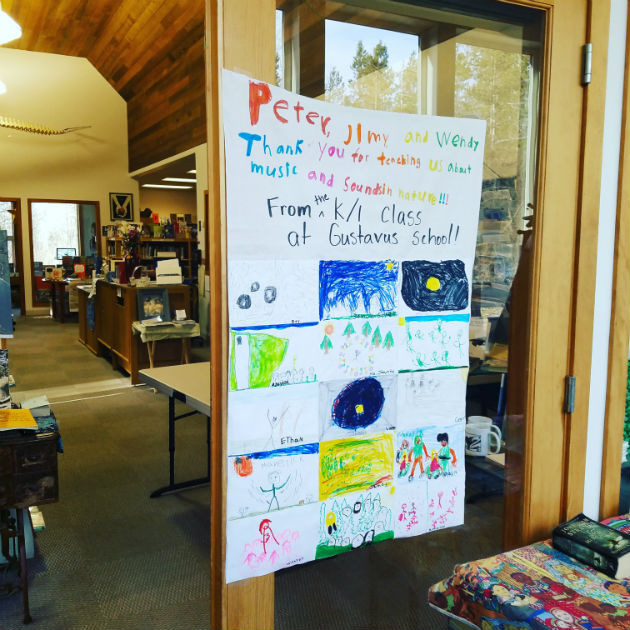

Tidelines Journey, the traveling residency dreamed up by Bradley, launched in 2016 with five artists signing on to visit eight communities over a month, via the Marine Highway. The journey was equal parts communal living onboard a ferry and homestays at each community stop. Environmental concerns were the focus of that first journey, which comprised community events where the artists presented and talked about work they had created in response to the issue. Residents in turn also made their own presentations to the assembled artists and their neighbors during those community gatherings. In addition, the visiting artists worked with the schools and students in each community.

|

|

Bradley believed that environmental issues could provide common ground for both the residents and the visiting artists, and indeed the topic was fruitful for all involved. “Everybody responded differently to [artist talks], and then the community conversations that followed carried this amazing sense of catharsis. It was really important to people to have a chance to just open up and talk about what they’re seeing and thinking about as they watch the landscape around them shift,” said Bradley. “It was clear on that trip that art was doing its job in terms of opening up new lenses of understanding for ideas that we’re all trying to find our way through.”

Bradley believes it’s especially important to have these kinds of artistic disruptions in isolated areas as a way to spark curiosity in places that might have gotten used to doing things a certain way. “For anything to change requires curiosity, and for new ideas to be sparked requires curiosity,” he said. “Art’s ultimate role is to weird the ways that we see the world, and offer [opportunities] to see through different lenses.”

Nina Elder, an artist and arts educator, helped Bradley to plan and facilitate the 2017 iteration of Tidelines Journey, which was supported by the National Endowment for the Arts. For this year’s month-long residency, which took place last April, four artists and roughly 500 residents participated around the theme of “Signal to Noise,” in terms of which voices are being heard and which are overpowered in conversations regarding the environment.

|

Elder agrees that curiosity is an important part of the project, both as a starting point and as an outcome. “I know a lot of the people that we talked to said that they often feel misunderstood or like they are this fringe of the United States,” she said. “To have [artists] show up who are truly curious and want to learn about

them helped reinvigorate their own curiosity about themselves and what they do and the poignancy and the power of how they’re living. Everyone from a schoolteacher to a fisherman to the garbage man, their lives are different in Southeast Alaska than they would be in the lower 48.”

She added that she was told by residents that they appreciated the artists’ visit as a focal point for building community cohesion, which in turn made them feel more comfortable and confident about tackling difficult issues. “People that were living in these towns were getting to know each other in new and meaningful ways because we were asking them to talk about and present themselves,” she said. “Small towns can always get to know each other better, we realized. Seeing how artists can address challenging issues was very inspiring to them as a community.”

While the first two Tidelines Journey residencies were by many accounts successful, the question remains of whether or not the interactions between artists and communities will have a lasting resonance. Bradley admitted that as the program is only two years old, it’s hard to say with certainty what change will come in the wake of the residency. Still, he hoped “that we could plant the seeds through this tour that would reverberate a while after we visited, and that people would be able to take the stuff of the tour and the ideas of the group from the conversations generated and use it how they wanted.”

Elder is equally optimistic about the residency’s ultimate outcome for the communities that participated. “I think just by being there and by modeling curiosity and by saying ‘Show me your town, show me what you love, show me what’s problematic, how do you townspeople creatively engage with this, what inspired you,’ [it will help] people then to amplify the future that they want to see in these places where they’re living. So it helps them see a more cohesive future or a more creative future.”