Music and the Mind

Music has always been seen as having healing properties—from ancient societies using music to unite communities and keep them healthy to singing as a way to soothe colicky babies. Much of the literature on the subject, however, has been anecdotal rather than scientifically based. But a new initiative called Sound Health hopes to change that.

A partnership of the John F. Kennedy Center for the Performing Arts and the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in association with the National Endowment for the Arts, Sound Health aims to explore the impact of music on health, science, and education, and how the brain processes music. A unique collaboration between a government scientific research agency and an arts presenting organization, Sound Health brings musicians and scientists together to present and demonstrate research results during an annual two-day event at the Kennedy Center.

The initiative came to being through a fortuitous 2015 meeting between Renée Fleming, internationally celebrated opera singer and artistic advisor at large for the Kennedy Center, and Dr. Francis Collins, director of the NIH. As Collins noted to NEA’s Director of Research and Analysis Sunil Iyengar in a 2017 interview, the goal of the initiative was “to say, ‘What could we do as the world’s largest supporter of biomedical research, to try to provide some kind of path forward that would further increase the scientific credibility and the potential power of music therapy?’”

“All these anecdotal stories about our music and what it does—science has to validate it,” noted the legendary percussionist Mickey Hart, multiple Grammy Award winner and former member of the Grateful Dead, in a recent NEA interview. He was involved in the Sound Health initiative in 2018, participating in a workshop at the Kennedy Center on how rhythm impacts language and healing with fellow musician Zakir Hussain, an NEA National Heritage Fellow, and Dr. Nina Kraus, a professor of neurobiology and otolaryngology at Northwestern University. “That’s why we’re here, because this is a music-science handshake.”

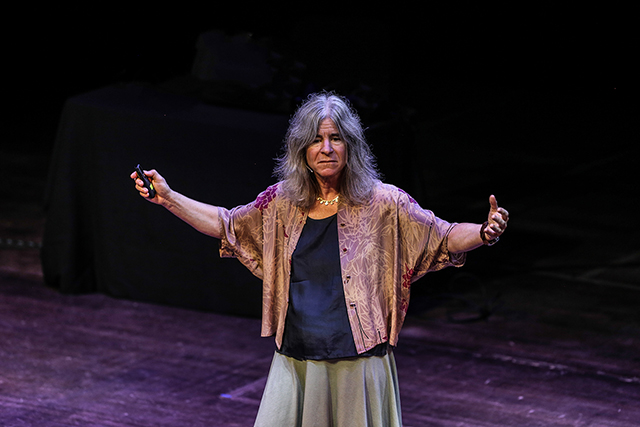

|

“The medical profession, as in any profession that deals with academics, needs proofs,” concurred Hussain, a master musician on the Indian percussion instrument tabla. “In ancient worlds like India or Africa, they already know certain things that help center us, keep us healthy, and in some ways heal us. And [musicians] talk about it in our own way, but that’s not the language of academia. It’s like taking a theorem and figuring out how to prove it, so it will eventually legitimize the information that already exists.”

For both Hussain and Hart, the increasing interest from scientists into the physical workings of music and rhythm reflects their own longtime musings on how the brain and music interact.

Music, Hart said, “goes to the brain, the master clock, and now we’re able to read the master clock. We’re able to see what neurons are firing when certain rhythms are played, so now we’re able to actually see the super organism, which is the brain.” Hart has worked extensively with scientists over the years to delve into how music affects people physiologically. He has collaborated with Nobel Prize-winning astrophysicist George Smoot on how to convert light wave traces from the Big Bang into sound waves to make music, and with leading neuroscientist Dr. Adam Gazzaley at the University of California, San Francisco to better understand how specific rhythms can stimulate areas of damaged brains.

During the Sound Health workshop that Hart and Hussain participated in with Kraus, they looked at the implications of rhythm on language. “There is rhythm in every kind of music,” Kraus noted during the workshop, “but there is also rhythm in speech.” By tracking how the brain reacts to rhythm, scientists can better understand how the brain reacts to speech and language development. In a study of low-income children, Kraus said, “we found the kids who were engaged in steady, continuous music-making were the kids who maintained their age-normed reading scores. There’s an important connection here: music therapy is another way of supporting language development.”

Hussain noted a similar connection between music and rhythm and learning during his NEA interview. “In India when you’re a child, there’s music in the house, and you’re taught songs and rhythms, so the stimulation is amazing. And you see all the Indian kids in this part of the world winning spelling bee contests and creating incredible programs for the computers and being scientists and doctors, and it’s awesome.”

|

A better understanding of how music affects the brain could lead not just to better education outcomes, but to more effective use of music therapy. This is an area that the National Endowment for the Arts has increasingly focused on in recent years. For example, the NEA convenes the Interagency Task Force on the Arts and Human Development, which brings together 19 federal agencies and departments (including NIH) to explore research gaps and opportunities for understanding how the arts can improve health outcomes throughout the lifespan. In collaboration with the Departments of Defense and Veterans Affairs and state art agencies, the NEA also developed the initiative Creative Forces: Military Healing Arts Network, which incorporates creative arts therapy into medical treatment for military personnel coping with traumatic psychological health conditions, as well as their families and caregivers.

When Fleming and Collins were first discussing what they could do together, they settled on what Collins described as “the growing field of music therapy,” which has proven beneficial to a wide variety of health issues, ranging from autism to Alzheimer’s disease. “[Medicine and music] have a lot to say to each other,” he noted, though they “haven’t necessarily been in the same room as maybe now they can be.”

Fleming, who has participated in Sound Health events at the Kennedy Center in 2017 and 2018, is hopeful that the project will continue to grow and provide the necessary research to better understand how music can improve people’s health. In a 2017 podcast interview with the NEA, she stated, “One of the goals of this whole collaboration is to further music therapy as a field, as a profession, and it has to do with the science.” She imagines a day when we might be able to explain why someone who might be unreachable through verbal or physical cues sometimes comes alive when hearing a familiar song. “It’s going to be a while before science connects those two dots in a meaningful way,” she said. “But in the meantime, we see that it works.”