Not Your Average Art Museum

The American Visionary Art Museum (AVAM) is nestled like a glittering jewel in the Federal Hill neighborhood of Baltimore. There are no white walls and solemn security guards telling children to quiet down. The gift shop stocks practical jokes and novelty sunglasses. In the permanent collection, a bedazzled bed frame featuring Alfred E. Neuman sits directly across from the sculptural magnum opus of a terminally ill mental patient, which was carved from a single piece of applewood. Neither work seems out of place. As the nation’s premier museum for visionary art, AVAM has made it a central exercise to pair exuberance with education when contemplating and curating life’s mysteries. In the process, it has elevated self-taught artists within the American canon, and showed just how much fun art museums can be.

Visionary art goes by many names: self-taught art, outsider art, and its original French counterpart, art brüt. AVAM defines visionary art as work created by self-taught artists, whose “works arise from an innate personal vision that revels foremost in the creative act itself.”

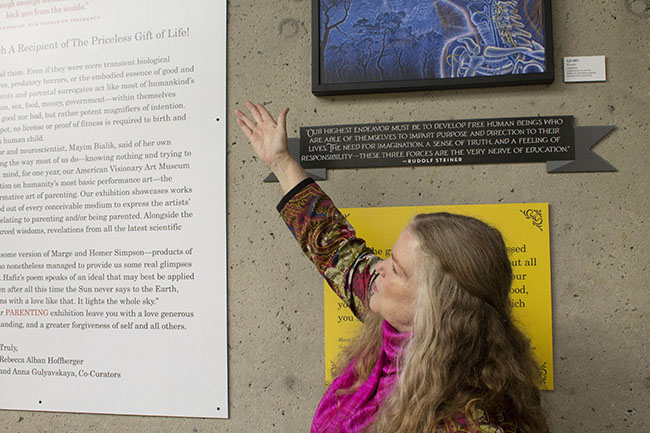

The museum itself grew from the personal vision of founder Rebecca Hoffberger, who had no previous museum experience before she established AVAM. Hoffberger left her hometown of Baltimore at age 16 to study under acclaimed mime Marcel Marceau in Paris, founded her own ballet company by age 21, established field hospitals in Nigeria, and spent several years practicing traditional healing practices in rural Mexico (all while raising two daughters). By 1984, Hoffberger had moved back to Baltimore, where she was working as the development director of People Encouraging People, a nonprofit providing transformative mental health rehabilitation at Sinai Hospital.

|

Hoffberger was intrigued by the intuitive creativity flowing from her patients, especially the art they created despite the lack of any formal training. “I’m very interested in where a fresh thought comes from,” said Hoffberger.

At the time, there was still little interest surrounding self-taught artists in the United States, and only a dozen or so visionary or outsider art spaces in existence worldwide. “For a long time before we opened, the outsider art movement was really controlled almost exclusively by four major galleries and they tended to show the same top 12 artists amongst them, and the prices went up, up, and up,” said Hoffberger. Undeterred, Hoffberger and her husband LeRoy traveled the world learning about visionary art, and opened the doors to AVAM in 1995. In 2004, they doubled their campus to its current 1.1 acre “urban wonderland.”

Today, people come from all over the world to see the museum and learn from its unique presentational and organizational structure. There are now more than a dozen museums, galleries, and art spaces centered around visionary art in the United States, largely in response to the success AVAM has seen. Part of the museum’s success is that, despite running on a budget that is a fraction of its local counterparts, AVAM is the only museum in Baltimore with rising attendance rates.

One of the reasons that Hoffberger believes her museum has become so successful is because of its accessibility. “I had the greatest edge of not going through an art history education,” she said. “You don’t want to write for your peers who went through the same linguistic educational system. You want to think about how you express and make connections with regular people walking in the door.”

|

The museum curates and presents art in a format that transcends intergenerational barriers that often plague traditional museums, hoping that everyone from five to 85 will learn or see something they never have encountered prior to visiting AVAM. Primary among its educational goals is to “expand the definition of a worthwhile life.”

The Visionary Art Museum is not about, “‘Let me tell you why this is an important era in art,’” said Hoffberger. Instead, she said, “It’s very oriented to wonder; what it is to be a human being, meaning all the negative traits that human beings have long had and struggled with as well as their best characteristics.”

The unadulterated testaments to joy, sadness, and humor hanging from the walls of the museum are not tempered by hyper-conceptual artistic trends popular within but not necessarily outside of the art world. Annual exhibit themes range from this year’s Parenting: An Art without a Manual to previous exhibits like Race, Class & Gender: Three things that contribute ‘0’ to CHARACTER, because being a schmuck is an equal opportunity for everyone!

Although Hoffberger often has a hand in exhibition curation, there are no permanent curators on staff, allowing guest curators to contribute their own unique voice to the already unique museum. Visiting curators have ranged from Simpsons creator Matt Groening to Ariana Huffington to Archbishop Desmond Tutu. Due to the relatively small size of the budget, staff members often wear many hats over the course of a year. At other museums, most large-scale temporary exhibits take years to plan, but according to Hoffberger, AVAM staff have always been “on time and on budget” with their grand exhibitions, putting them together in roughly nine months. This is even more impressive when you consider that the majority of the administrative staff, like Hoffberger, has no traditional background in museum studies, although most have experience in the arts.

While AVAM has significantly legitimized and raised the profile of visionary art in the United States, its contributions to the local community of Baltimore are also significant. “More urban museums present as fortresses saying, ‘Stay out, we have valuable things inside,’” said Hoffberger. “Ours has always been a wonderland that you come up to at 3am and hug the Cosmic Galaxy Egg outside and you could walk on our property or you could skateboard here and be welcome to do so.”

|

AVAM demonstrates this through an extensive commitment to education and grassroots community initiatives, including the famed Baltimore Kinetic Sculpture Race, its annual Martin Luther King, Jr. Day celebration, apprenticeship programs, neighborhood movie nights, and more.

Social justice and grassroots education inform almost every facet of the museum, including the exhibition themes, community outreach events, and even the mosaic adorning the main building. The mosaic, titled Shining Walls / Shining Youth is the result of the largest apprenticeship program for incarcerated or at-risk youths in the country, according to the museum. It is dedicated to LeRoy Hoffberger, who passed away in 2013. The program “encourages teamwork, pride in creating something both exquisite and lasting, and results in real job skills, useful for the rest of their lives,” according to the museum. This project, along with the museum’s other community initiatives, has created a deep sense of respect and interchange between the Visionary Art Museum and the community in which it exists.

Hoffberger recalls the doubt cast in her direction during the beginning stages of AVAM, but was willing to take the risk of following her intuition to present those artists who had been marginalized by more conventional art museums. Though AVAM may lack the size and budget of other art museums, its impact cannot be denied.

Or as Hoffberger quoted friend Dame Anita Roddick, “If you think you’re too small to make a difference, try going to bed with a mosquito.”

Sophia Salganicoff was an intern in the NEA Office of Public Affairs in fall 2018.