Breaking the Chain

One of the early Cave Canem retreats. Photo courtesy of Toi Derricotte

One of the evocative structures that emerges from the volcanic soil of Italy’s ancient city of Pompeii is the House of the Tragic Poet, named for the remnants of wall frescoes depicting scenes from Greek mythology and Homer’s Iliad. The house also features a mosaic embedded in the floor of the vestibule of a black dog, alert and ready to spring forward but for the chain around its neck. Below this canine guardian are the words CAVE CANEM, Latin for “Beware of the Dog.”

Poets Toi Derricotte and Cornelius Eady visited Pompeii and the House of the Tragic Poet in 1996, a day after they had decided to build a home for Black poets on their own, for their own. And so, Cave Canem became the name and emblem for their literary venture, only in their rendition of the Pompeiian image, the chain that restrains the dog is broken.

Themselves Black poets, Derricotte and Eady saw the lack of representation for poets of color in published books, academic programs and faculties, and among the winners of literary prizes. They wanted to create a place where Black poets could break from their isolation and be with one another, share their work without having to explain or defend it, and that could provide the kind of support that would lead those poets toward successful careers.

Cave Canem founders Toi Derricotte and Cornelious Eady (in back) at an early retreat with, from left, Sarah Micklem, Father Francis Gargani, Lucille Clifton, Sonia Sanchez, Michelle Elliot, and Renee Moore. Photo courtesy of Cave Canem

In the beginning, those who participated in Cave Canem Foundation programs were, as described by Ruth Ellen Kocher—poet and associate dean for Arts and Humanities at the University of Colorado as well as a Cave Canem participant— “not so much seeking to effect change in the literary landscape as much as we were acknowledging...the exclusivity of that landscape and creating a homestead for ourselves, and that homestead became a sprawling estate with considerable acreage.”

Twenty-five years later, what started as a one-week retreat with about 30 poets has become a sweeping force that has helped change the face of poetry in America. The organization has nurtured almost 500 Cave Canem fellows who have gone on to publish lauded books, to win prestigious prizes such as the Pulitzer Prize in Poetry, and to become valued teachers in community programs and universities across the country. Its Poetry Prize has launched the careers of many, and its myriad other programs touch many more writers and readers every year.

The National Endowment for the Arts has provided support for Cave Canem since 2000, and many Cave Canem fellows have been awarded a Creative Writing Fellowship in poetry from the Arts Endowment.

THE RETREAT

Each year, Cave Canem receives about 300 applications for the 15 spots available for first-time fellows. The remainder of the 40 spots are taken by fellows from previous summers who are able to return twice more. Fellows attend the retreat on an income-based sliding scale and then have access to other opportunities both at Cave Canem and with other organizations. (Because of the COVID pandemic, the summer retreats are currently on hold.)

The schedule is intense. In between shared meals are readings, or a speaker, or a workshop, along with the requirement that each fellow produce one poem each day, due at 10:00 every morning.

Although poets come to the retreat for professional development, they also come for community. Major Jackson is the author of five books, recipient of an NEA Creative Writing Fellowship in 2015, and is now the Gertrude Conaway Vanderbilt Chair in the Humanities at Vanderbilt University. Jackson was in the inaugural class of fellows in 1996 and said, “Many of us who were there had a very strong sense that this was a unique and historic moment. We may not have understood at the moment the reach of Cave Canem, but the general feeling [was] of kinship, community.”

Kocher reiterates the imperative for her of finding community at Cave Canem. She became a fellow in 2002 and received an NEA Creative Writing Fellowship in 2017. She describes the first night of the retreat that always starts with a welcome circle, each fellow introducing themselves to the group. “As you make your way around the circle, you realize everyone there—I mean almost everyone there—has some narrative to share about feeling like the outsider and how this project has brought them into a place where they feel accepted, and they feel like they belong.”

The 2019 class of Cave Canem fellows. Photo by Marcus Jackson

PRIZES AND PROGRAMS

Cave Canem awards three different poetry prizes, but its signature award is the Cave Canem Poetry Prize. It began in 1999 and recognizes an outstanding manuscript worthy of publishing as an author’s first book. In addition to getting their work published, the winner gets a cash prize of $1,000. Publishers rotate among three small presses. For 2021, the publisher is Graywolf Press, a longtime NEA grantee.

The list of recipients for the poetry prize is distinguished for its prescience in honoring notable achievement. Natasha Trethewey was awarded the inaugural prize and would go on to receive the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2007 and serve as U.S. Poet Laureate from 2012 to 2013. Tracy K. Smith’s The Body’s Question was selected in 2002; she was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry in 2012 and also served as U.S. Poet Laureate from 2017 to 2019. Major Jackson, who won the prize in 2000, said that it, “launched in earnest my career as a published poet.”

Cave Canem engages its widest audience through its community workshops with nearly 1,000 poets participating since 1999. These sessions are designed for emerging poets who have published no more than two books and are not enrolled in a literary degree program. Held at different levels of experience, the ten-week workshops are rigorous. Currently, workshops have switched to virtual platforms as have other programs including Writers Worktable, which offers insights into the business of poetry and First Books, a discussion series in which two poets—one emerging, one established—talk about their first book.

Cave Canem has shared its wisdom with other groups of writers and been a model for literary communities seeking to make a larger and better place for their artists to thrive. Among those is CantoMundo, serving Latinx poets, and Kundiman, advancing Asian-American creative writers; both organizations are supported by the Arts Endowment. Jackson said that as a result of this leadership in the literary field, “we have decentered whiteness and particularly white male poets as the sole producers of literature in the country. We understand the wealth of the nation as a result of its art and how that art reflects back to us the power of a pluralistic society.”

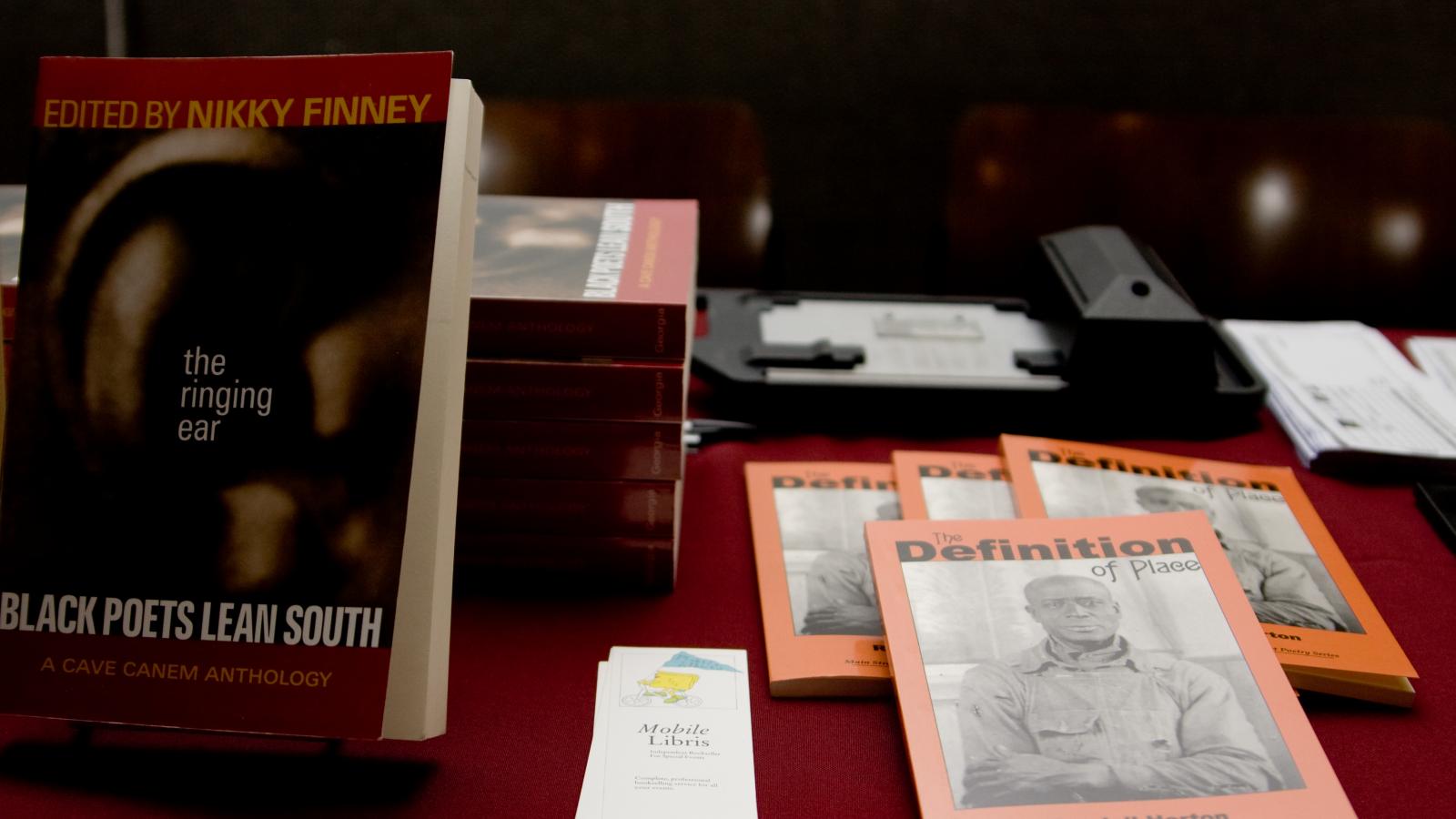

Some books by Cave Canem fellows. Photo courtesy of Cave Canem

CHANGING THE LITERARY LANDSCAPE

Today, the world of poetry by Black writers is indeed very different. In the words of Tyehimba Jess, chairman of the Cave Canem board of directors and a Pulitzer Prize-winning poet, it is “furiously flowering,” which is also the name of the Furious Flower Poetry Center at James Madison University, the nation's first academic center for Black poetry. He notes that young Black poets today tend to have greater “academic sophistication” from attending MFA programs early in the careers but that their poetry is nonetheless “rooted in the soul and the essence of Blackness.”

The growth in poetry’s popularity is reflected in the NEA’s own research. According to the Arts Endowment’s most recent Survey of Public Participation in the Arts, between 2012 and 2017, the percentage of adults who read poetry increased by 76 percent and the share of adults 18-24 years old who read poetry more than doubled. Among racial/ethnic subgroups, African Americans, Asian Americans, and other nonwhite, non-Hispanic groups read poetry at the highest rates overall.

In recognition of its many accomplishments, the National Book Foundation awarded Cave Canem its Literarian Award in 2016 for service to the American literary community. It was the first time that the $10,000 prize was awarded to an organization instead of an individual.

Reflecting on the organization’s history, Kocher said, “The writers who first went to Cave Canem went back to their communities and worked as poets…and mentored another generation, who came to Cave Canem and then went back to their communities, and it became very cyclic in that way…. It’s amazing for me to see the landscape of young Black poets now and how they’re really on fire with the confidence and support and community that they gain through the [Cave Canem] Foundation.”