Music Credits:

Excerpt of “04 - B-40 _ RS-4-W _ M23-6K” composed and performed by Dave Holland from the cd Emerald Tears.

Excerpt of “Directions” composed by Joe Zawinul and performed by Miles Davis from the album, Live at the Fillmore East, March 9, 1970: It’s About That Time.

Excerpt of “Conference of the Birds” composed by Dave Holland and performed by the Dave Holland Quartet, from the album, Conference of the Birds.

Excerpt of “Prime Directive,” composed by Dave Holland, performed by the Dave Holland Quintet, from the cd Prime Directive.

Josephine Reed: From the National Endowment for the Arts, This is Art Works. I’m Josephine Reed

Dave Holland: I came to America—it was part of a dream, really—to come to New York and to play music here, and to learn. I never dreamt it would be with Miles Davis. But when I got here, I found a community of musicians that welcomed me into the music. And when I got the news of the award, I was very moved because I felt to have the community honor me with this award meant a lot to me and to feel that my journey here had culminated in this wonderful experience and this wonderful acknowledgment, and I appreciate it very much.

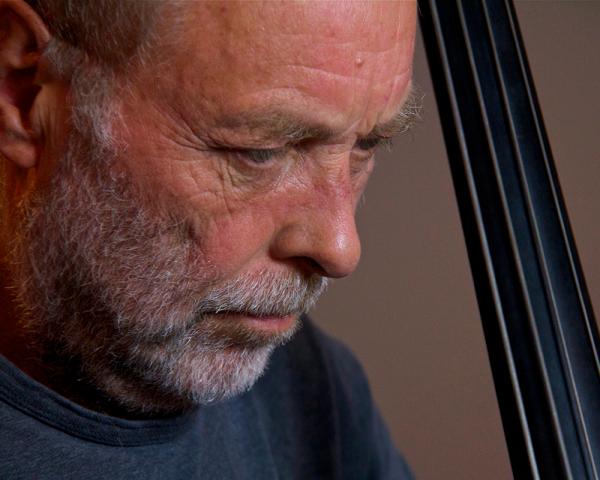

Josephine Reed: You just heard bassist Dave Holland, talking about his NEA Jazz Master award. And since we are celebrating the 2024 NEA Jazz Masters this coming weekend on April 13, I thought it would be a good time to revisit my 2017 interview with Dave Holland

Dave Holland is one of the most versatile bassists in jazz. He works seamlessly across different styles of playing from traditional to avant-garde, from world music to folk. Holland is also an accomplished composer and bandleader, bringing together musicians of exceptional talent and giving them the room to play. His compositions run the gamut from solo pieces to big bands, all wrapped around the bold layered melodies of his bass playing. In a career spanning five decades, he continues to evolve musically with each new project. Yet, the sound of his bass playing is unmistakable. A multiple Grammy Award winner, Dave Holland can be heard on hundreds of recordings, with more than thirty as a leader under his own name. It’s an extraordinary achievement for anyone—but even more remarkable for a boy born into the English working class in the middle of the last century, and who got his start on the ukulele.

Dave Holland: My uncle had various hobbies, so one of them was to play the ukulele. He bought a ukulele, and I showed an interest in it and just started pretending to play it, and he said, “I’ll show you a couple of chords.” I was four or five years old. And I said, “Please,” and that was it. I was—I’d spend hours playing this instrument, and that was the beginning of it. And then, you know, rock and roll happened, and the influx of American music into England. So by 1956, I wanted a guitar for my 10th birthday, and my mother got me one.

Josephine Reed: Why did you move from the guitar to the bass?

Dave Holland: I’d been fascinated by the bass. I loved the sound, but I loved the function that it played in the music, you know, both rhythmic and harmonic. It seemed to have a central role in the music to me, and it just—

Josephine Reed: And often understated.

Dave Holland: Yeah, and it suited my personality. I was a little shy, you know, as a young person, and I—I don't think I was cut out to be a—a lead guitarist or anything. And the—just the position of the bass in the—in the group kind of suited how I felt, and I loved the range of it. I loved what it provided to the music. It was just something that seemed central to—to everything, you know, rhythmically and harmonically, you know.

Josephine Reed: You’re in a band, like a lot of teenagers, how did you begin to start playing professionally?

Dave Holland: Around that time, I started hearing Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley and Ray Charles and some of the great R&B singers and things like that, and we used to just do cover versions, played dance halls and—and clubs, and that was how it all started. And then, by the time I was 15, I decided I was going to leave school and be a musician. I was already working and making some money, playing these little gigs.

Josephine Reed: Did you go to London at that point?

Dave Holland: No. I was living in the—in the midlands area. You know, at that time, the opportunities in the midlands was—for a working class kid, were very limited. You know, for a lot of us, growing up at that time in those areas, music was a kind of window to the world, and it offered a—a—an opportunity to reinvent your life, in some ways.

Josephine Reed: And when did jazz enter the picture? Were you listening to jazz at that point?

Dave Holland: I was interested in it. This is when I left school at 15, I said, “Well, I’m going to start to really check out the bass from all—all possible angles now.” So I opened a Down Beat Magazine, and it happened to be the poll winner magazine, and Ray Brown’s name was at the top of it. So, not knowing who he was, I went to the record store and found two records with Ray on it, with Oscar Peterson, and at the same time found two Leroy Vinnegar records, the great bass player from the West Coast. I took these four records home and put them on the record player, and that was it. It changed—that was this new—new direction to my life. I mean, I just wanted to play that way and I realized, you know, what was possible with the bass, you know, way beyond anything I had imagined before that.

Josephine Reed: What did you hear when you listened to them that made you sit up and truly take notice in that way?

Dave Holland: Well, I mean, the first thing that hit me was the sound that they made.

And the second thing was the feeling that came out of their music. But the other part of it was that, for me, one of the beautiful things I love about music is the communal aspect of it, and the sharing of creating music together. And what I heard in the way those two gentlemen played was a supportive and interactive role with the musicians in the band in a way that I’d never heard before. So it opened up another world of how music could be put together, but also how communication can happen within a—within a group. But I think the magic for me has always been that element of dialogue and communication in the music, and that’s what impressed me initially on those records, of course.

Josephine Reed: And is that when you began playing jazz yourself? Did you—did you get an upright bass at that point?

Dave Holland: I got an upright bass within about two weeks of hearing those records, yeah, but I didn’t start playing outside of the house. I was playing with the records, and I was learning everything I could learn from those records, trying to copy everything I heard. And all this is by ear, of course. And then I started to go to some jazz clubs locally and listen to the local musicians. And I moved to London and—and worked there for a year, and that was my beginning of living in London and finding a teacher there and so on.

Josephine Reed: After moving to London, Dave Holland studied with James Merrett, who was the principal bassist in the London Philharmonic Orchestra. Dave then went on to study bass at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama for three years. All the while, continuing to play gigs around town.

Dave Holland: I started working my way through the jazz scene in London starting in 1960, ‘65. But what happened also was I started meeting young players that were my own generation, and we were interested in—of course, in all the new music coming out of Ornette Coleman’s music, and John Coltrane, and Miles Davis, Cecil Taylor, Albert Ayler—these were all influences on the music scene in London. And I’m so grateful for the kind of education that I got from the community in London. And in 1966, I got an opportunity to start working at Ronnie Scott’s. Jazz was becoming more predominant in my life as terms of the music that I felt that I could really put my heart and soul into, and—and that would be a statement that was coming from me rather than an interpretive statement of somebody else’s music.

Josephine Reed: And Miles Davis saw you at the Ronnie Scott Club.

Dave Holland: Yeah. I was working there at that time in the support band. And we were playing opposite the Bill Evans Trio. Somebody said, “Oh, Miles is coming in tonight,” and I thought oh, that’s pretty amazing. He’s going to be in the club. But I didn’t think for a minute he would be listening to what we were doing. That was my first underestimation of Miles, of course, because I think he was always checking things out. So we—we played through to the last set of the night. I was just going on for that final set. And Philly Joe Jones was living in London. And I’d got to know Philly Joe. And he came to the bandstand as I was getting on stage and said, “Miles wants you to join his band,” and I said, “Come on now. You’re kidding,” you know. Philly Joe Jones was quite a joker sometimes. I said, “Come on. You’re putting me on. Don’t say that.” He said, “No, it’s serious. He wants to see you after the set.” So, I kind of got myself together, finished the set, and then I went looking for Miles, and he’d left the club already. Now, Philly was still there, and so I said, “What’s—what’s happening?” He said, “Oh, he wants you to call him tomorrow morning at the hotel.” So he gave me the name of the hotel. So about 10:00 in the morning, I gave him a call. He’d checked out and gone back to America, right? So, there I am with this idea that maybe I’ve got the gig but no way to find out. So I called Philly Joe again and I said, “What do you think? Is this real?” He said, “Well, he wouldn’t be telling you that if he didn’t mean it.” So he said, “Just sit tight. You’ll hear something.” So a week went by, two weeks went by, three weeks went by. So, I was just starting a gig at Ronnie’s with—with Joe Henderson, and I got back at three in the morning, something like that, and my phone rang and it was Miles’ manager, Jack Whitmore. And he sounded just like a caricature of an American manager agent. I could almost see the big cigar and everything, you know. And he said, “Miles really wants you to come over and play with the band.” He said—this was a Tuesday, by the way. He said, “He’s got a gig starting at Count Basie’s in Harlem on Friday. Can you be there?” And of course, my whole life is happening in England, and I—without hesitation, I said, “Yeah, of course.” And––

Josephine Reed: How old were you?

Dave Holland: I was 21. And I arrived in New York on Thursday. I went to Herbie Hancock’s apartment, as instructed, on Thursday evening, and Herbie, who was very gracious and didn’t know who the heck I was but was very nice to me, invited me in and he showed me a couple of things, and that was it.

Josephine Reed: And you hadn’t met Miles yet?

Dave Holland: Hadn’t met Miles yet, and I turned up at the—at Count Basie’s and got my bass onstage. The drums were set up. And as I told you, I was a little shy, so I was just standing at the back of the club, sort of waiting to see what’s happening. And, you know, I saw people arriving, but still nobody said anything to me, and then Tony Williams arrived and went onstage. I saw Herbie heading to the stage and Wayne and Miles. I thought, “Well, I better get up there.” So, I went and picked the bass up, and Miles just went to the mic and started playing, and that was it. I got to speak to Miles after the first set.

<music up>

Josephine Reed: How did you claim your space within that band?

Dave Holland: That’s a great question, because, you know, any time you have a—a group that has been together for so long—that particular band must have had six—six years or so together. There’s so much understood between the musicians that’s not even to do with what’s written in the music. There’s a language that’s been developed during those years. So it’s, as you say, finding a place for yourself, and I—the first night, I was kind of waiting to be invited in, in a way, musically, and I realized that wasn’t happening, that they were just going ahead and playing. And I felt a little bit disconcerted as to whether I was being welcomed musically, although Miles, you know, said a couple of nice things to me the first night. I went back and said, “I’m wondering if this is going to work out, you know?” And I was reading a book of aphorisms of Sufi literature, and I opened the book at a page that said, “Plant your banner firmly in the desert sand.” And when I read that, I—I thought about it. I said, well, your banner is your identity, and you plant it firmly, resolutely, and I thought that’s maybe what I need to do. So in the next night I came back and I started kind of just going for it, instead of waiting to have a space made for me. This was New York, you know? I should have known this, right, but it’s my first time in New York. It’s almost my first time outside of England. So I just started sort of trying to make my presence felt a little bit more.

Josephine Reed: I’m curious about playing with Miles as another musician, but then also with Miles as the leader. What kind of a bandleader was he? What was he like to work for, if you will?

Dave Holland: I think the first impression that I got was—was just the intent that was coming from his playing. It was another level of concentration, another level of immersion in the music, you know? In other words, it was—you—you have to be in there all the time, because it was moving, the music, all the time. Miles had directions that he was looking to move in. But he looked very much into the musicians to fill in those spaces. He wasn’t a dictator at all. He didn’t tell you what to do or how to do it, really. He wanted you to bring what you had and to give it all and to serve the music that he was putting together.

Josephine Reed: You played with Miles for two years, and it was a time of transition for that band. You left after two years. What was your thinking?

Dave Holland: I think any time you’re with Miles it’s a time of transition, you know? I think this is one of the things that was so amazing about his music, that it was always in movement. We were also using electric piano and the electric bass. The last three months of touring with Miles, I didn’t take the acoustic bass on the road with me at all, and I started to feel that—that I was moving away from what I was really wanting to be able to do or play the instrument I really wanted to play. And I’d started on a project with Chick Corea and Barry Altschul. We’d been playing as a trio at times when Miles wasn’t working. And we met up with Anthony Braxton and decided to put a band together as a—with the four of us. So we went from playing to half a million people at the Isle of Wight, to about 30 people in a little club in San Francisco, you know?

Josephine Reed: That was a big transition.

Dave Holland: It was, you know, but I’m—you know, my whole life, I’ve been following the music. That’s been the motivating force for me. And if I see a musical direction I want to go in, you know, I’m pretty determined about it. There wasn’t even a hesitation. I feel like I have to be involved in something that’s really key to where I’m going with the music, and that was what that decision was about. It was simply the—to follow a musical train of thought.

Josephine Reed: And your first album as a leader is Conference of the Birds, which had Anthony Braxton and Barry Altschul and Sam Rivers.

Dave Holland: Yes, exactly. And that was the first album. Yeah. It was done in three hours in New York. They were almost fir—all first takes, you know. That was the—we had two hours to set up and three hours to record. I think it was five or six hours all together.

<music up>

Dave Holland: You know, I was really happy because it did what I’ve always hoped records would do, which is document a moment in time. It documented a relationship, a musical sound that we were making together, and that’s—that, to me, has always been the purpose of the recordings is to—is to document the events that are going on, you know, the performances that are happening.

Josephine Reed: You played with Sam Rivers for a good 10 years.

Dave Holland: I did, yeah.

Josephine Reed: What was it about his playing that worked so well with you, but also obviously challenged you?

Dave Holland: Well, Sam’s music covered a range of history, you know, from rhythm and blues, traditional music, and up into the contemporary music of the time of—of the ‘70s and ‘80s. And playing with him gave me opportunity to actually go in any direction I wanted to. In the small group, we never used any written music, so it was all improvised, so every night it was like a blank page of paper that we would fill in with whatever we were thinking about that day. So I felt like it fulfilled, at that time in my life, an opportunity to really explore all kinds of avenues of music. I worked with several other ensembles until about ’76, and then from ’76 to ’80 I decided only to work with Sam. I literally didn’t take any gigs with anybody else. I just felt a freedom of music with him that was extraordinary.

Josephine Reed: It makes sense to go to your solo career—talk about a sense of freedom. What—what different sets of challenges of cutting a solo album, what did that present to you?

Dave Holland: Well, first thing I think is convincing people a solo bass performance is something that’s of any value, you know? You know, a solo bass? What can you possibly do with a bass on its own, you know? So, I started thinking about how to present the bass in many different ways and different characters, in a way that would make the sound of a solo instrument for an hour, an hour and a half sound interesting, and pacing it with compositional material that would have enough variety to keep people’s intere—interest, keep my interest. So I did the solo album in 1977, called Emerald Tears, again for ECM Records, and following that started doing some solo concerts.

<music up>

Dave Holland: It was really great. I felt, you know, the chance to really think about the instrument in that way taught me a lot about it.

Josephine Reed: At the beginning of the ‘80s, you put a band together, a quintet. Can you walk me through that process? Why the decision to lead a band, and what you wanted to say as a leader?

Dave Holland: By ’81 I was 35, I guess, and I was starting to think that there were music that I wanted to play that I maybe needed to put a band together to do it. It was a big step forward to take. And not only that, you’re sort of coming out of the shadows a little bit as a bass player.

Josephine Reed: You know, you mentioned something you heard from Miles, which is having to have a point of view—

Dave Holland: Yeah.

Josephine Reed: ––as a player, and I would think most specifically as a leader. Can you—can you say a little more about that? I found that very intriguing.

Dave Holland: Yeah, and that was the difficult part for me because I’d always worked in more cooperative situations, and I found it difficult at first to draw a line in terms of where I—how I wanted things to be done and things like that. Not in a—not in a dictatorial way, but just to—to make just, you know, basic decisions about things actually. So, for me, it was a matter of finding that balance, as Miles did so beautifully, you know, which was to make the necessary decisions, but leave so much there for the creative musicians that you’re working with so that they have a—a say and a statement in where the music’s going.

Josephine Reed: When you’re composing improvisational music, are you composing for the musicians that you know you’re going to be working with?

Dave Holland: Most of the time, I would say, and sometimes you write a song just because it’s there and you—you know, you—it’s just asking to be written. But the—most of the time, everything I’ve written, almost exclusively, has been for some kind of performance or some kind of group, and that’s going right back to the very beginning.

Josephine Reed: So how much do you notate and how much do you leave for the musicians to fill in?

Dave Holland: You know, obviously, it’s different with different context. With a big band, when you’ve got 13, 15 musicians, you have to notate a lot more. So it varies with different contexts, but I kind of follow Miles’ premise that less is more, you know. The less you put on paper, the more opportunity you have for things to happen.

Josephine Reed: Prime Directive was a very important album for you. Can you….

Dave Holland: Very.

Josephine Reed: ––talk about the philosophy in forming it?

Dave Holland: Prime Directive was the first album that featured Chris Potter on it. The rest of the band on that CD was Robin Eubanks on trombone, Billy Kilson on drums, and of course Steve Nelson on vibraphone and marimba. You know, when you start a band, you never know where it’s going to go. I didn’t know what would happen with that group, if it was going to be together six months, or it would be one record. Ended up being together for 12 or 13 years. And it was just the right combination of people at the right time, the right time in my life when I think I was really clear about where I was going with my own playing and the music I wanted to do, and they were the right people to be with me on that journey. And it was an amazing period of time to spend time with those musicians, who I still play with, of course.

<music up>

Dave Holland: I decided that I was going to make the Prime Directive, that things had to be fun, and if there was any problems that—you know, coming up, then it was time to change something. So that’s where that term came from, Prime Directive, is to make sure that not only is it serious, but it’s also fun to do.

Josephine Reed: You had said that one thing you learned as you got a bit older playing jazz, was that it was really about telling a story. And I wonder if you feel as though you’re telling different stories—a different story with the quintet than you’re telling with the big band, or they’re variations on the same story?

Dave Holland: That’s a good question. I—I think, when I said that I’m referring a bit more to the personal experience of playing as a—as an instrumentalist, you know. I think the—the storyteller as a composer is usually a mood, an impression, sometimes a narrative that you’re trying to get across, you know. But this—what I was referring to there is the idea that—that you need to play from your life experience, you know. And I think as a young player, you know, you’re still coming to terms with learning the mechanics of the music and the language and, you know, you don’t necessarily connect it up with your life in the same way. And you start to realize that the notes on their own don’t really mean that much, that they need to connect up with some feeling that you have and with some story or some aspect of your life story that you feel and, you know, the good and the bad, all of those things are present. And I know, for me, that the things that I’ve been through in my life have certainly helped give me an emotional store of things to—to draw on and to express, you know. And you don’t necessarily think of them in a conscious way, but you—when you play, you connect up with your feelings.

Josephine Reed: You do a lot of work in education and—and working with younger players.

Dave Holland: Yeah.

Josephine Reed: What is it that you try to impart to them as jazz musicians?

Dave Holland: Well, I guess the two things you do is you try and introduce them to the heritage of the music and where it’s coming from, and I would say not only musically, but historically, the—the social context of it, so they understand a little bit more about the—the source of the music and what it means, you know. And then the other part is to try and give them some—the tools that they need to discover what they have to offer, and that’s a very important part for me is to try and get into their head and find out what is the music that they’re feeling strongly about and how to help them realize that, as well. So, the—the tradition gives the foundation, and then you try to help them have the courage and put in the work to discover what their contribution can be.

Josephine Reed: When you look back at your own career, how do you see your own evolution as—as a player and as a composer?

Dave Holland: Yeah. I see it as a step-by-step process. I just work from day to day, really, and try and build from what I learned yesterday on when I work today. But the evolution has only taken place because of the musicians I’ve been with. I can’t say that strongly enough, you know. This is not something you do in isolation, this music. It’s something that’s a shared event. We work as a community in this music. Ideas are shared, experiences shared, and then it’s passed on to other generations. People from diverse backgrounds, diverse cultures can come together and find common ground and work together to make something beautiful happen.

Josephine Reed: That is bassist and 2017 NEA Jazz Master, Dave Holland. The Arts Endowment in collaboration with the Kennedy Center will celebrate the 2024 NEA Jazz Masters Gary Bartz, Terence Blanchard, Amina Claudine Myers, and Willard Jenkins with a tribute concert on Saturday, April 13 at 7:30 pm. The concert is free and open to the public. You can get ticket details at Kennedy-Center.org. And if you can’t make it to DC, don’t despair, the concert is available through a live webcast and radio broadcast at arts.gov. You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Follow us wherever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on Apple—it will help people to find us.

For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.