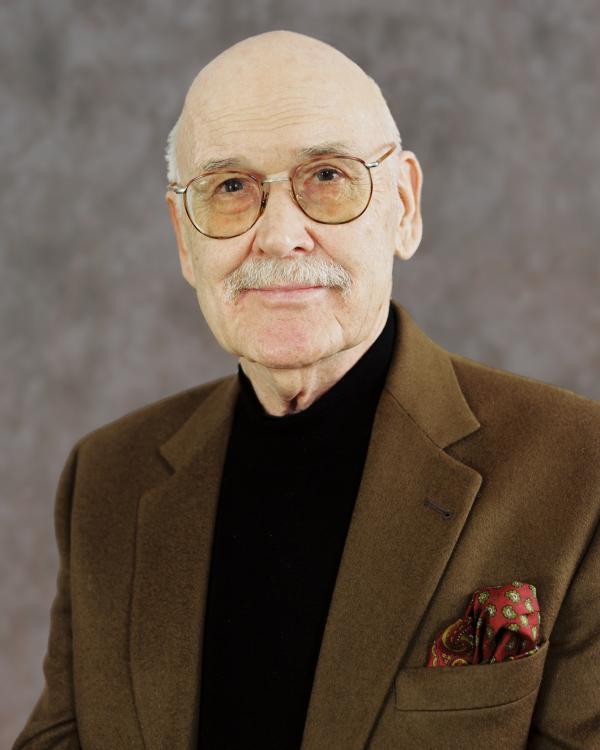

Jim Hall

Photo by Tom Pich/tompich.com

Bio

Jazz guitarist Jim Hall's technique has been called subtle, his sound mellow, and his compositions understated; yet his recording and playing history was anything but modest. He recorded with artists ranging from Bill Evans to Itzhak Perlman and performed alongside most of the jazz greats of the 20th century. The first of the modern jazz guitarists to receive an NEA Jazz Masters award, his prowess on the instrument put him in the company of Charlie Christian, Wes Montgomery, and Django Reinhardt.

After graduating from the Cleveland Institute of Music, Hall became an original member of the Chico Hamilton Quintet in 1955 and of the Jimmy Giuffre 3 the following year -- both small but musically vital ensembles of the era. Hall continued to hone his craft on Ella Fitzgerald's South American tour in 1960, a fruitful time in which his exposure to bossa nova greatly influenced his subsequent work. From there, he joined Sonny Rollins' quartet from 1961-62, and appears on The Bridge, Rollins' first recording in three years after a self-imposed retirement. The interplay between Rollins' fiery solos and Hall's classic guitar runs make this one of jazz's most essential recordings.

Hall then co-led a quartet with Art Farmer, recorded a series of duets with noted saxophonist Paul Desmond, and performed as a session musician on numerous recordings. His extensive ensemble experience has produced a control of rhythm and harmony so that Hall's playing, while grounded in scholarly technique and science, sounds both rich and free.

He eventually formed his own trio in 1965, which still performs and records today. Well-studied in classical composition, Hall has produced many original pieces for various jazz orchestral ensembles. His composition for jazz quartet, "Quartet Plus Four," earned him the Jazzpar Prize in Denmark. In 2004, Towson University in Maryland commissioned a work by Hall for the First World Guitar Congress, Peace Movement, a concerto for guitar and orchestra performed by Hall and the Baltimore Symphony.

His influence on jazz guitarists, including such disparate ones as Bill Frisell and Pat Metheny, was immense. Hall explored new avenues of music, even appearing on saxophonist Greg Osby's 2000 recording, Invisible Hand, with legendary pianist Andrew Hill. He worked in smaller settings as well, often in duets with jazz greats such as pianists Bill Evans and Red Mitchell, and bassists Ron Carter and Charlie Haden. In addition to numerous Grammy nominations, Hall was awarded the New York Jazz Critics Circle Award for Best Jazz Composer/Arranger.

Selected Discography

Jimmy Giuffre 3, Trav'lin' Light, Atlantic, 1958

Sonny Rollins, The Bridge, RCA, 1962

Ron Carter and Jim Hall, Live at Village West, Concord, 1982

Something Special, Music Masters, 1993

Jim Hall and Bill Frisell, Hemispheres, ArtistShare, 2007-08

Interview by Molly Murphy for the NEA

November 6, 2003

Edited by Don Ball, NEA

EARLY INFLUENCES

Q: Tell me a little bit about some of your early experiences with listening to music. It seems like a lot of people have kind of a pivotal experience where they hear something and it strikes them in a way that music has never struck them before.

Jim Hall: The thing that I call my spiritual awakening was that I heard this marvelous guitar player, who I think already had died by then. He died when he was about 24. I heard him on a record, a Benny Goodman record. It was Charlie Christian. I had been playing the guitar about three years, I guess, so I was 13 and working in this group that had a clarinet, accordion, drums, and guitar. It was kind of typical of Cleveland. And the clarinet player took me to a record shop. They were playing a Benny Goodman record and the tune was called "Grand Slam.

I heard Charlie Christian play, I think, two choruses out of "Grand Slam," which is a blues in F-major. I remember thinking I wasn't even sure what it was he was doing but I said "Whatever that is, I wish I could do it." And now when I hear the same record, I have the same feeling. I think Charlie Christian was a brilliant guy. I've seen some of the stuff he wrote for Downbeat and there was an incredible musicality. Previous to that, the first guitar I heard was [my] Uncle Ed, in the hillbilly part of Ohio, who sang and played the guitar, sort of country music. He always had cute ladies around him and he drank a lot, so that must have registered with me.

Q: You said 'I'm going to take up the guitar?'

Jim Hall: Darn right, yeah. I actually wrote a piece called "Uncle Ed" two or three years ago. It was dedicated to him. Anyway, I had heard him. Then my mom bought me a guitar when I was nine or ten. I just started taking regular lessons and played with it. That's when I heard Charlie Christian. That was it.

Q: And when you hear that recording now you said you listen to it now and you're still --

Jim Hall: I feel the same way. I'm awestruck at his choice of notes and the space that he left. He was also supposed to have been part of the bebop evolution up at Minton's Playhouse in New York because he would go up there for jam sessions with Thelonious Monk and all those guys. Obviously I never knew him because he was gone. He had tuberculosis. So that was it and so I've been kind of after that ever since.

I got the Charlie [Christian], I got the Benny Goodman. It was an album of 78 [inch] recordings. I don't think we had a record player at first. The album was called Benny Goodman's Sextet and I remember carrying it on a bus to some friend's house to play. Then I got Art Tatum records, Coleman Hawkins, and all those guys. I'd wait until my mom went to work and to play those things 'cause she liked Guy Lombardo and Hawaiian music and probably church music, stuff like that.

Q: Did you have anyone guiding you towards guitar playing?

Jim Hall: Oh, yeah. I had some terrific teachers. The most important one is retired in Florida and I'm still in touch with him. He's a great guy. He's very much still involved. His name is Fred Sharp and he was a marvelous teacher. I think my first guitar cost 75 bucks at this store -- I think it was Wurlitzer Music -- and I'd take a lesson every week and part of the lesson money would go toward the guitar.

I somehow just assumed I was a musician -- or was going to be one -- I studied big band arranging for a while when I was about 15 with a guy named Joe Dolny.

This was in Cleveland, Ohio. I guess I figured I wanted to be a better musician. Somehow I got into the Cleveland Institute of Music which was a shot in the dark because I didn't really know anything about music schools. It just happened there were some amazing teachers there; some of them were refugees from Europe. I was there for five years.

Q: And so when you were at the Institute of Music you studied composition?

Jim Hall: Yeah. There was no jazz taught and no guitar.

Q: No guitar?

Jim Hall: No, they didn't have classical guitar. So I played on weekends. This was in 1950. I was 19 years old and had to take six months or a year to get my piano playing together so I could audition and everything. Our family -- well there was just my mother and my brother and me -- we really had no money at all. We lived in a housing project in Cleveland. The woman in the office, her husband was a bass player and a composition major there, so she knew me. I was allowed to pay the tuition a couple hundred bucks at a time and I got some little scholarships. Anyhow, I made it through and then started a Master's in composition. Something happened: I panicked. My composition teacher, who was amazing, was a Viennese composer. He knew Arnold Schönberg and all those guys. I think he scared me, frankly. My excuse was I wanted to try being a jazz musician. So I took off and went to California to seek my fortune.

CHICO HAMILTON

Q: And how did you hook up with Chico Hamilton?

Jim Hall: My friend Joe Dolny was in Los Angeles. I knew that Joe was out there and I had an Aunt Eva who was in her 90s who had an apartment and she let me sleep on her couch, so I figured I had it covered. Joe had a rehearsal band at the musicians' union once a week. A lot of really terrific players from some famous big bands they'd come in or studio players that wanted to play good music. So they had a French horn player named Johnny Graas. And he was starting a group, so I went over to Johnny's house to rehearse. It was a wild coincidence. Chico called while I was there and he told John that he was starting a group and was looking for a guitar player. So John says "here" [hands Hall the phone], so really that's how it happened. It's pretty amazing. I was talking with Chico.

That was a perfect job for me because it had the cello. Fred Katz played cello. Carson Smith was a marvelous bass player. Buddy Collette played all the woodwinds (flute, clarinet, tenor, and alto), and Chico and me.

Q: You had really interesting instrumentation.

Jim Hall: Yeah. And I recently saw a video of a TV show we had done, just one tune. We played something of Buddy's and the group sounded nice.

Q: Can you talk a little bit about his approach to the drums?

Jim Hall: He's very inventive. Dramatic, I think. I remember when he played a solo, he would use the tom-tom sticks a lot. I forgot what they're called. Mallets. Mallets of forethought.

I thought it was creative of him to have a cello in the group. He had played with Fred Katz who had played piano behind Lena Horne for a while. That's how they knew each other. Fred wrote things. Buddy Collette and I did most of the writing.

SONNY ROLLINS

Q: Ah, how did you meet Sonny Rollins?

Jim Hall: [Chico's group] played opposite Max Roach's group at Basin Street East, and it had Sonny Rollins, Clifford Brown, Richie Powell -- who's Bud Powell's younger brother. I'm drawing a blank on the bass player's name. I got to know those guys and Sonny. I eventually hooked up and I worked with Sonny. It was a perfect job actually.

Q: What were your first impressions of Sonny Rollins?

Jim Hall: The same as my last one. He's incredibly gifted. He has a wild presence. I remember being in the kitchen at The Village Vanguard. I worked opposite Miles Davis' group for a while with Lee Konitz. In the kitchen all the guys would be using bebop talk.

Q: Do you remember how you got in touch over that recording [Sonny Rollins' The Bridge]?

Jim Hall: Yeah. I was living in Los Angeles, as I said, and a bunch of things happened. I had gotten to know John Lewis -- I did a record with John, Percy Heath, Chico, and Bill Perkins, who had played with Kenton's band. It was called Two Degrees East, Three Degrees West , which is funny because I'm not from the West at all. Anyway, John called me and said, "You have to come back to New York." John was doing a score for Odds Against Tomorrow , which is a Harry Belafonte movie. He wanted me to be on that and do some other things. So I said, "Where am I going to stay?" And he said, "Well stay at my place. I'm never there anyway." So John had this terrific apartment at 10th Avenue and 57th Street. Miles Davis lived down the hall too, so I stayed there.

It was a great apartment and John would be home part of the time. One day the doorbell rang and I went to the door and it was Miles Davis. He said, "Jim, what are you doing here?" I told him "I settled. I'm staying here. I'm staying here until I can find a place on my own." He says, "Are you trying? Are you looking?" So he invited me down to his apartment. He was just about to do that Sketches of Spain CD with Gil Evans and he was playing some music for me. I met his mom down there and his wife. (Boy, he's another one of my heroes. I always felt that Miles could play silence better than most guys could play notes.)

So then what happened? I got a sublet. Dick Katz, it was Dick's apartment and he was away for a while so I stayed there. Then one time I got a note in the mailbox and it said, "Dear Jim, I'd like to talk with you about music. Signed: Sonny Rollins." My phone probably had been disconnected for non-payment. I can't remember how I knew where he lived. It was right near the bridge there. I walked down there 'cause I couldn't afford a taxi and I left him a note that said something like, "Dear Sonny, I'm home a lot and I'd love to talk about music."

And so he stopped by the apartment one time. I think it was on the fourth floor. He sat down -- we sat sort of facing each other at this little round table -- and put a plastic bag down on the table. He started talking, he's so dignified. An incredible guy. All of a sudden the bag started trembling. It got my attention. He'd go on, "I have these other two fellows, Bob Cranshaw and Walter Perkins, they've been working together with Carmen McRae. I'd like you to join." Then the bag sort of jerked around. I said, "Sonny, what is that?" Typical of him he said, "I'll tell you about that as soon as we finish this." That's the way he is. So I said, "Yeah, I'd love to do it." And then he said, "Okay, I'll show you," and he opened the bag. It was a little lizard or chameleon that he bought. He said, "Look here. Isn't he great?" He wouldn't be interrupted that way, just went straight ahead. Then we started rehearsing at the old Five Spot.

Q: What was it like to play with him?

Jim Hall: Well, it got my attention. I really loved Sonny personally but didn't understand what a fantastic, I want to say natural, musician [he is]. He practiced really hard, obviously. Probably stopped traffic a lot. But he would do things automatically, motive development and things like that, things I paid money to learn in music school. He has a solo on that tune "St. Thomas," on the trio record from a long time ago, where he picks up a two-note motive from the bass player at the end of the one chorus or the melody and he develops that for about three days. He would just take a tune apart sometimes: bring us to a halt by the strength of his playing. He would examine the tune from top to bottom, and then he'd take it out. So that was great.

JIMMY GIUFFRE

Q: I don't want to skip over Jimmy Giuffre.

Jim Hall: There were these jam sessions on Sunday afternoon at a club in L.A. I think it was called Sardi's or something like that and I remember I met Giuffre. He's from Texas, of course. I said, "Mr. Giuffre" or "Jimmy" or whatever I said, "Boy it's such an honor to meet you. I really love your playing and your writing." I said, "It's really a pleasure." And he says, "Same to you."

Yeah, I think I probably learned more from Jimmy, in a lot of ways, than anybody else. It was a great experience.

Q: Why is that?

Jim Hall: Well, Jimmy is a very schooled musician. He wrote an album for strings and clarinet one time. I guess it was called The Jimmy Giuffre Clarinet. It was beautiful. He asked me to write the liner notes. He had a sense of the trio that there should never be just a clarinet out front and we were the accompaniment.

WORKING IN INTERRACIAL GROUPS

Q: Were there problems because you were in a lot of interracial groups?

Jim Hall: The only pressure I ever felt was to play better, I swear. I think about it. Also I think having heard Charlie Christian that time. I said it was my spiritual awakening. I'll show you some pictures of him. He was pretty dark brown, from Oklahoma City, I forget. Anyhow, if anybody would say something negative about African Americans when I was a kid, I must have almost unconsciously thought if that's true, how come he's playing like that and I'm playing "Come to Jesus?" And that really helped. I don't know. Color and nationality just seemed to have nothing to do with things within music anyway.

Q: You never felt excluded?

Jim Hall: No, not a bit. I had one interesting experience though. I was working with Art Farmer and Steve Swallow who is also Anglo Saxon, I guess. We were with Steve and Walter Perkins on drums -- either that or Pete LaRocca. I think it was Walter. We played on the South Side of Chicago at McKee's Lounge. It's a great place. And we played opposite Redd Foxx. He was great. One night [Foxx] said, "Come on let's go get some snack or early breakfast or something together." So he took me to this place called Glady's on the south side of Chicago -- I think I was the only non-African American -- a great big restaurant and he introduced me to people and they were lovely. Everybody liked me. "You come back" and all that stuff. And the next night I told Steve and his wife Helen, "You got to come with me for dinner to this place called Glady's. They know me and everything." We got there and it was kind of crowded at the door. We could not get a table. That's the only time I ever felt it, and I was embarrassed and Steve was cracking up. And then I thought, "Dummy, you were here with Redd Foxx last night." They probably thought we were students.

I never felt excluded but I did start to notice finally how injured people are by racial garbage. I think Chico will verify this when we traveled in cars and station wagons and if we were in the South, not even too far south, Chico would stay curled up in the back seat. I'd be sent in for food and stuff like that. People would think I was the manager sometimes, and I was the most unmanageable person in the group usually. But there's this incredible camaraderie among musicians, especially jazz musicians anyway.

PLAYING THE GUITAR

Q: How do you approach a solo? What do you think makes a good solo?

Jim Hall: It's kind of hard to say but for me. What seems kind of frivolous and doesn't really impress me is guys, people, women -- some terrific women guitar players, too -- who have amazing technique but everything sounds worked out. They go through these chord changes with all these chops. Usually, I feel, I wish, I had kind of technique to do that and then not do it, sort of. I like to make some kind of composition happen while I'm playing. That involves motive development, which is partly from Charlie Christian, partly from my schooling, and partly from Sonny. I think. It seems to work for me. I also love melodies. So I try to play melodies over tunes -- have it go some place and then come back. It's never over. For instance, the guitar is sitting there frowning at me now, which is the good part. It was like a carrot on a stick or something.

Q: Do you play every day?

Jim Hall: Oh, I've been writing this piece and there's the score right there. I still have some stuff to finish. But I literally didn't play for weeks and I'm just starting to practice again. I didn't have any calluses or anything.

Q: Is that unusual?

Jim Hall: I usually at least touch it [his guitar] every day and my practicing is usually pretty specific. Well, in some ways it is. One of the specific things I do is to try to play kind of atonal stuff that makes sense just connecting strange intervals in a musical way and finding them on the guitar. And maybe trying to play just on one string for a while and see how that feels -- or else there will be a tune that I'm scuffling with and I'll work on that. But I'm sort of into slow practice I think. So, yeah, I practice every day pretty much and I think I'm more influenced by saxophone players, and maybe piano also, than by guitar.

I heard Don Bias early on records and Coleman Hawkins. I actually got to play with Coleman Hawkins a couple times, just for one night, and then later on I worked with Ben Webster for a while in California. That was a great experience. And I love the breathing and the phrasing and the sound of that kind of tenor saxophone player.

Q: Do you ever have that in your mind when you're playing your guitar? Do you think horn when you're playing?

Jim Hall: Probably...and then I sort of sold out a few years ago. I got some foot pedals. I always [had] this kind of snobbery. I don't know what it was [that] I don't want to use any electronic gadgets. I've always felt that I actually use the amplifier in order to play softer, because you can pick the guitar pretty softly and it'll still project. So you can get a tenor saxophone sound without banging away. But I found that the foot pedals throw my brain into a different orbit and it actually helps, as long as you don't overdo it.

BASS AND GUITAR DUETS

Q: What is appealing about bass and guitar duos?

Jim Hall: A bunch of things. One is that you're equal parts of the duo so you don't do a lot of standing around and grinning while the other guys are playing. Part of it is having gone to music school. I played bass for a while in the orchestra -- terribly -- and then when we'd have the concert, they'd get guys from the Cleveland Orchestra and I'd move down to the end. I hear the bass fiddle as a lower extension of the guitar so I automatically listen to what the bass is doing and all my chord voicings are related, I hope, to what he does. Especially with Ron Carter, who has a really daring harmonic sense. He'll go all over the place with his lines, try different things every chorus. And so it's just fun. It's like talking with you as opposed to a whole group shouting at each other. I did a lot with Red Mitchell, who was just amazing. Jack Six, another bass player. Oh boy: Percy Heath. I played a duet with Percy at John Lewis' service, I remember. We played "Django," which is nice.

AUDIENCES

Q: How do you feel about an intimacy in a performance? Do you prefer small clubs? Is it important for you to relate to your audience?

Jim Hall: I think it is. I realize it after the fact but -- in a lot of ways -- it's important. And especially after the World Trade Center went down. I went to Europe just two or three weeks after it with Greg Osby, Terry Clark, and Steve LaSpina, who is a marvelous bass player. We haven't played together in a while. Anyway, we got such empathy all over. We were in Italy, in Macedonia, and in Southern and Northern Ireland. All these allegedly dangerous places, and Germany. I think we played in Berlin. But my point is that I learned how to say "peace" as best I could in all the languages. And we would play just a free improvisation at the end and dedicate it to peace. So, I think it's really important. I'm feeling that more and more that -- and had for years -- these, I wouldn't even call them political leanings, but just feelings about people that I thought were being violated. But I always said, "Well, play your music. That's your contribution." Because you're doing something that people do together.

NAT HENTOFF

Q: Let's just ask you a couple of things about Nat Hentoff.

Jim Hall: & I've known Nat forever. He was in Boston. Of course, he actually knew Ben Webster and people like that. I remember he interviewed Charles Mingus one time. And then, what the heck happened? Mingus got up on a table -- so Nat jumped up on the table with him. Nat had a radio show in Boston. I remember being interviewed there. And then, he wrote liner notes for one of my CDs. He is really knowledgeable.

We differ on some things, of course, which makes it nice.

Q: Do you fight about them?

Jim Hall: Not really. Bruce Ricker did a video of me called Life in Progress. So Nat came up and talked about me, and he was great.

But for instance, I don't think he really liked the direction that Miles Davis took towards the end. I figured Miles was trying to keep growing. He was trying different things. It's, like, if you hated Picasso's last year's things and you wanted him to go back to the Blue Period.

NEA JAZZ MASTER AWARD

Q: How do you feel about the term "Jazz Master?" Being deemed an NEA Jazz Master?

Jim Hall: I guess, it works for an award. It's never mastered. Well, I got this booklet from the NEA, with photographs of some of the people that have received it in the last 20 years. It's just absolutely stunning company to be in...The women and men who have received this award in the past have been creatively spreading love, good will, and friendship among people. Something that the world would do well to emulate...And it's so great that that's being recognized.

That's my main feeling about it. It just went from a musical feeling to a feeling of inclusion. What an honor to now be among the peacemakers.