Music Credit:

“Icefire” composed and performed by Pat Metheny, from the album, Watercolors, used courtesy of ECM and by permission of Songs of Kobalt Music Publishing a/c Pat Meth Music Corp, BMI.

“Walter L” composed by Gary Burton and performed by Burton, Steve Swallow, Pat Metheny and Antonio Sanchez, from the album Quartet Live, used courtesy of Concord Records and used by permission of Grayfriar Music, BMI.

“Missouri Uncompromised” written by Pat Metheny, performed by Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius and Bob Moses from the album Bright Size Life. Used courtesy of ECM.

“Airstream,” written by Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays, performed by the Pat Metheny Group. Used courtesy of ECM.

“Geneology” written by Pat Metheny, performed by Pat Metheny and the Unity Group. Used courtesy of Nonesuch.

“One Quiet Night” written and performed by Pat Metheny, from the album One Quiet Night. Used courtesy of Warner Brothers.

“Spirit of the Air,” written and performed by Pat Metheny from the album Orchestrion. Used courtesy of Nonesuch.

“Song X composed by Ornette Coleman and performed by Metheny, Coleman, Haden, D. Coleman and Jack Dejohnette, from Song X, used courtesy of Nonesuch/WBR and used by permission of Phrase Text Music a/c Songs of Kobalt Music Publishing , ASCAP.

<Music>

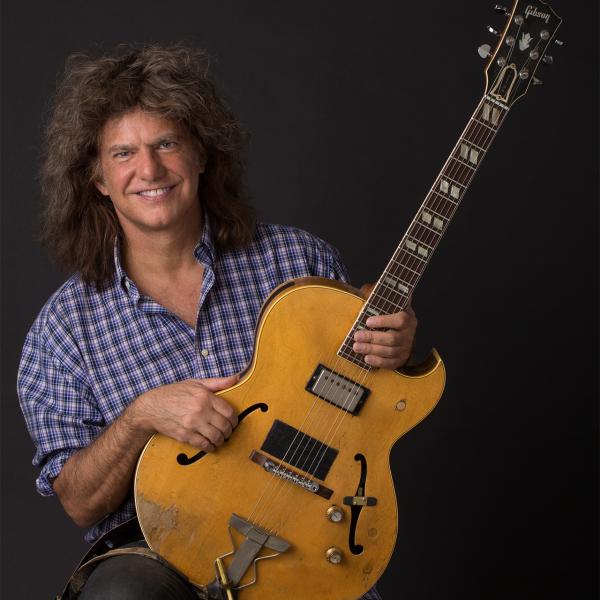

Jo Reed: You’re listening to 2018 NEA Jazz Master, guitarist and composer, Pat Metheny and this is Art Works the weekly podcast from the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Pat Metheny reinvented the traditional sound of jazz guitar. Whether playing his own compositions or one of his wildly inventive improvisations, Pat Metheny shows a deep musicality while pushing the boundaries of jazz guitar. He is one of the few artists who has achieved crossover popularity with three gold records as well as critical acclaim. Over the course of his career, Pat Metheny has won 20 Grammys in ten different categories. And in 2013, He became only the fourth guitarist inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame.

Pat Metheny’s music resists an easy description, he casts a wide musical net, from modern jazz to rock to country to classical. He cut his teeth as a teenager playing with jazz musicians in Kansas City. He joined Gary Burton’s band when he was 20, cut his debut album at 21 and began The Pat Metheny Group at the tender age of 23. And he’s never looked back. From that first album Bright Size Life to present day, Pat Metheny continues to push the music and reshape the possibilities for jazz guitar for both players and fans. I spoke with Pat Metheny in a New York rehearsal space—so you’ll occasionally hear the sound of traffic and sirens. Throughout the conversation, Pat recounted the significance of his musical influences throughout the years….beginning the small Missouri town where he was raised.

Pat Metheny: Well, I was born in Kansas City, Missouri, grew up in a very small town called Lee’s Summit. The thing of growing up out there has been something that I’ve always tried to represent. You know, just the nature of the landscapes out there, there was like, a lot of space. But more specifically, the nature of the sound out there. That’s been a part of my life from the ground up. That’s a sound that I know. It’s been a source of material and inspiration for me.

Jo Reed: You grew up in a musical household, didn’t you?

Pat Metheny: I was lucky to be a member of a family where music was kind of a central thing. I mean, my older brother Mike––fantastic trumpet player, almost like a child prodigy kind of guy. My dad was a very good amateur trumpet player, and my mom’s dad was a professional trumpet player, so trumpet was everywhere. And me, too; I started on the trumpet when I was eight. The trumpet thing has remained kind of a constant for me. I mean, even now, when I’m playing, you know, on the guitar, I’m kind of thinking trumpet. So it’s real deep, that trumpet thing for me, and I would list among my most important influences trumpet players. Certainly, Miles Davis is, like so many people, probably the major reason that I’m even involved in this general area of music. Hearing one of his records when I was about 11 changed my life. It was like somebody hitting me over the head with a baseball bat, like, what is that? You know, it should be noted I was a terrible trumpet player. I often joke that when I would play a note, birds would drop from the sky, you know. It was really bad, and it was a good move to get off that act and go someplace else.

Jo Reed: Now, why the guitar? What was it about the guitar that just grabbed you?

Pat Metheny: Well, I’m chronologically right at that spot where the guitar sort of became more than just an instrument. It was almost an iconic example of something that was happening in the culture that signified this big change that was just about to go down. You know, I think I responded to that, to the way a eight- or nine-year-old kid would when, like, a billion other people, I saw the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, and suddenly, that instrument had a place in my consciousness that just, it did not before. Where my story is a little different is that not long after that is when I heard this first Miles Davis record, and I went completely there. It seemed to me that the music really established what the culture was about to become. To me, there was something about that, that it was like something is about to happen—more than an electric guitar, it was that.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny started playing with other jazz musicians in Kansas City when he was a teenager. His role model in those early years, the legendary Wes Montgomery.

Pat Metheny: Wes is still, hands down, one of the major musicians in my life. I think that there’s a normal trajectory that many young musicians follow, which is you have a few favorite players. You know, you emulate them to a degree, best of your ability early on, and Wes was the guy for me, no question. The first year I played, I played with my thumb, and when I would do the octave kind of thing as a young kid, on the gigs that I was lucky to find myself on, people would respond to that. And yet, at the same time, I was kind of hyper-aware of, you know, how that was kind of a violation of what actually the music represents, which is a certain kind of personal honesty and personal authenticity of being who you are. And when I think about every one of my favorite players – the people that I find myself responding to the most – are the people who are able to capture the things that they really love about music, and represent them in a way that, given my interests, fulfill a certain musical level of content. But beyond that, show something about who they are, where they’re from, what they love in music, and all the different ways that music can come to have meaning. So yeah, kind of early on, I realized whenever I would go into my Wes thing, I was not really honoring that mandate. And, maybe it’s, to me, one of the under-reported glories of this form is that it doesn’t just ask that you bring who you are to the thing; it demands it. The musicians who have really been able to contribute are people who bring something kind of their own design that comes out of who they are in a way that’s really true, and I’ve really tried to get to that.

Jo Reed: It’s no easy thing developing musical chops and creating a style that’s unique and authentic—to honor the traditions but keep pushing the music forward. Pat worked hard, even demonically on the guitar. No question about that, but his approach to the music is deceptively simple.

Pat Metheny: The way music has unfolded for me has been primarily built on just being a fan of music, loving music. Which as far back as I can remember, I was constantly involved with trying to understand what music is and how it works. And the next stage for me, if there’s something I really love, it’s how did they do that. What is involved in making that sound happen? And, kind of across the board, I mean, again, regardless of how you want to place it on a stylistic spectrum, the music that I feel like I’ve offered over the course of all this time has been a real reflection of what I love as a fan. I mean, if you look at the musicians I’ve worked with, that’s pretty much also the same list of musicians who are my favorite musicians as a fan. And, you know, when I think about Gary Burton, I was such a fan of that music fairly early going, I was like okay, so how do those tunes work? How are they put together? I think through understanding; you start to garner a certain wisdom about things, how it all goes together, that with the key element of being around a lot of good musicians, which I’ve always been very fortunate, to this day, to be able to say that I am. You have a chance of maybe getting to something. But it’s really difficult, you know? There’s one thing that doesn’t really get discussed that much, which is music is really hard. It’s hard to be a musician – and at the level that we’re talking about – and especially year after year after year after year after year, to maintain even on an aspirational level. That standard is something that is both incredibly difficult, but also, the greatest possible way to go through life because you learn so much about so many things by understanding music. In my case, I could probably be considered functionally illiterate, based on the fact that getting interested in the music that manifested itself in practicing 10 or 12 or 14 hours a day, every day. And as a result, starting in sixth grade, I never took a book home. I mean, the fact that they let me graduate from high school was like a mercy graduation. But, along the way, I learned about science, math, history -- everything through music.

Jo Reed: Let’s talk about Gary Burton. How did you meet, and how did you join his band?

Pat Metheny: Gary is such an important, huge figure for me in so many ways, I mean, starting with the fact that that band, the Gary Burton Quartet of the late ‘60s that was like the Beatles for me. That was the band that somehow seemed to have their finger on the pulse of that moment within the realm of improvised music that was unlike anything else. I think their well noted for that as well. Beyond that, the particulars of the language that Gary was addressing were especially resonant to me in the sense that it was kind of a rhythm section band. You know, there wasn’t a piano player. The guitar was almost functioning in the role of a horn player. And, you know, when I heard those records, I just couldn’t get enough of them and followed that band really closely.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: I had played the Wichita Jazz Festival a couple times when I was, you know, a really young teenager. And the woman that ran the Wichita Festival got in touch with me, I was already teaching at the University of Miami at that point, and said they were going to bring Gary to be in the festival. And when I heard Gary was going to be there, I was like, definitely, I’ll come up for that. When I got there, there’s Gary Burton, and it had kind of been arranged. I would play on that set too because he wasn’t there with the band. And, you know, so he’s there at the rehearsal with all these people and there’s a tune of Gary’s called Walter L that I started playing when I was maybe 14 or 15 years old. And the band director guy, who I knew, said “well, what do you want to play?” And I said, “well this tune, Walter L.” So me and the rhythm section started playing it, which of course caught Gary’s attention, because it’s not a easy kind of a tune; it’s a kind of weird tune. It would be like if somebody started playing one of my really difficult tunes, I would notice it. So he started playing with us, and we played this tune, and it was like, you know, a dream come true for me to just hear that. And then the band director said okay, well you guys will play, you know, the big band stuff with Gary. And that was the first time I got to play with Gary. He was very nice. He came and heard my set and gave me a lot of compliments mixed with criticisms, as became the thing with us over those next few years, very valuable criticism, too. But as I mentioned, at that time, I was teaching at the University of Miami. He was giving me the rap about, you know, maybe you should think about moving to New York, he said, “Or maybe you should move to Boston,” you know, “As kind of an in-between thing, would you like to teach at Berklee?” And I was like, “Sure.” So I came up to Boston, really thinking maybe if I get to Boston, maybe he’ll hire me and I can be in the band, and that’s exactly what happened. Yeah, from that point forward, I continued to play with Gary for another two and a half years, or two years, and every night was an amazing experience for me to just hear him, not to mention Steve Swallow, who I would put right there with Gary as a major, major influence for me.

Jo Reed: I just have to ask you to go back very quickly, because you say you were practically functionally illiterate, yet you were teaching at the University of Miami.

Pat Metheny: That’s one of those things that looks really great in the press kit. It wasn’t nearly as dramatic as that. It’s hard to even imagine this, but in 1972, the electric guitar was not considered an actual instrument. The University of Miami decided that they were going to have an electric guitar program. The dean of the University of Miami, Dr. Bill Lee, came and kind of recruited me like somebody would recruit a football player, which I have to say, for my parents, that was the happiest day of their entire lives. So I go to the University of Miami and within a week or two, I realized, you know, I’m not going to be able to pull this off. And also, I’m playing with all these great musicians, because it was a weird kind of moment that happens every now and then, where a bunch of really talented people all kind of wound up there. And so I want to Dr. Lee, and I was like, “Dr. Lee, thank you, but you know, I really can’t do this.” And as it happened, because they had opened up the electric guitar program that semester, they were expecting six electric guitar players, of which I was going to be one. They had 80, and one teacher. And it was, like, kind of a crisis. And because I had, at that point, played, you know, for four or five years almost I was, you know, a kind of a professional musician, I guess you could say. So he asked me if I would teach, which I said, “Can I stay in my dorm room and teach?” And he’s like, “Yeah.” And so, I no longer was a student, but I taught for two more semesters, and then started teaching at Berklee for two more semesters there, and then moved on to just playing all the time.

Jo Reed: While Pat was all of 21 and playing with Gary Burton, he recorded his debut album—Bright Size Life on Manfred Eicher’s ECM label.

Pat Metheny: The mind of ECM, Manfred Eicher, heard me on the first Gary Burton record in 1974, and offered me the opportunity to do a record. Gary being Gary said, “You’re not ready to do a record. You might only get to do one record in your whole life, so you better make sure that it’s THE record.” And in retrospect, I realized he was right, but at the time, I was like I want to do it now, you know. But his wisdom prevailed, so I did wait––I mean, it was a year and a half, as I think about it now; it seemed like 20 years at the time––to, you know, really write that bunch of tunes that became the tunes on Bright Size Life. That, you know, are arguments that I still feel are valid arguments. I could play every tune on that record right now, and I still can sort of say yeah, that’s talking about stuff that’s important to me. And I’m not sure I would have done that a year and a half before then, and I do have to really give Gary a lot of credit for that.

<Musical Interlude>

Jo Reed: After playing with Gary Burton for three years, Pat decided to strike out on his own and form the Pat Metheny Group—which was a daring move on his part, since he was very young and very broke.

Pat Metheny: Honestly, happened way faster than I ever would have expected that I became a leader. I was interested in dynamics. And I was interested in long-form development and a kind of band sound that was not about backbeats but more about the kinds of almost orchestrational elements that I didn’t see anybody else doing. You know, I think I had run a poll or some—or two, maybe, around that time, and so there was a lot of interest. I just kind of said okay. I just kind of went with it. I had met some really talented younger musicians who were ready to go, and I took the money I had saved from my paper route as a kid in Lee’s Summit and bought a van from my dad, and we were like the Blues Brothers. We were, like, on a mission from God and played every gig you could possibly play in the United States, and in that three years, put almost 300,000 miles on that van, with no roadie or crew for the first two years. Yeah, I mean, that was kind of the way it went. And back then, it was not really that different than now. It’s like the only thing you can really do with this music is go out and play, because there’s no real natural audience for any of this. You know, people often say, like wow, it must’ve been so great in—back then. It was impossible then the same way it’s impossible now. The only thing you can do is go out and play. And, you know, I think that if you have something to offer, that music is impervious to anything. And I’ve always built on that as a truth.

Jo Reed: The Pat Metheny Group first album was Watercolors, and they were off to the races…

Pat Metheny: Man, nobody was more surprised than me about that. People didn’t sell large numbers of records back then. And it wasn’t like I was trying to do that. I mean, the tunes on that first group record were 12 and 13 minutes long. It wasn’t like oh, let’s make some radio-friendly tunes here. But it sold, I mean, you know, hundreds and hundreds of thousands of records and not just a little bit of that was because of the amount of gigs we were doing. We were out there playing all the time. It was mystifying to me, and yet at the same time, it kept going. I mean, I did a solo guitar record after the first group record called New Chautauqua that was even more successful than that first group record. And then comes American Garage, which was, you know, at that same level.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: Again, I have to put a lot of the weight of why that is to the amount of gigs that I’ve done. I mean, you know, everybody knows the numbers of—you know, I mean, there’s probably not too many people you could find over the last 40 years that would have a number higher than mine in terms of gigs played.

Jo Reed: Pat’s closet collaborator in the group was without doubt keyboardist Lyle May—Lyle May was co-composed many of the tunes with Pat and also provided orchestrations and arrangements for the band. With that six-sense many musicians have, Pat knew Lyle would be a great partner before they even played together.

Pat Metheny: Well, I heard Lyle. You know, I’d already made Bright Size Life, had, you know, been playing with Gary for a few years. Lyle was to play on a Wichita Jazz Festival, and I was coming back to play with Gary on that same festival. So I went, and I heard his concert, and it was fantastic, and I realized right away, like, man, I could play with this guy. I know I could play with him. With Lyle, I could tell he was listening. He could really listen to the cats he was playing with. That’s what it all is, anyway, is listening. It’s not even playing; just listening. And I was like man, this guy can really listen, and he could play. And then we started playing, and that became the band. Lyle is an incredible musician, one of the most amazing musicians I have ever known. We can just play together, and I’ve experienced that with, not a lot, but a few musicians over the years, Charlie Haden and I were like that. There’s just some people you meet, and you’re like one right away. And you know, Lyle’s one of those few people for me, no question.

Jo Reed: Now, because you tour so much it means you’re playing out constantly. Choosing the musicians you play with becomes so much more important because obviously, you don’t want anybody to be mailing this in night after night after night. So how do you choose who you play with?

Pat Metheny: It’s a really good question, difficult to answer. I mean, of course, a lot of it, for me, kind of depends on, what story you want to tell at that particular moment. And there are certain people who would be, you know, cast perfectly to tell this story who would be terrible to tell that story, and so forth. Because the range of interests that I have as a musician is so wide, it’s always been difficult for me to find people who can just hang. And one other quality of my thing, it turns out, is that there’s a kind of deceptive simplicity to it all. It sounds like, that doesn’t seem like that would be that hard. But actually, those tunes are pretty hard. I mean, I’ve watched a lot of really hardcore beboppers crash and burn on the bridge to James, and there’s a lot of tunes like that. But the larger issue becomes something that has nothing to do with music, which is, you know, can that person hang, as a person, night after night after night after night after night, and be cool. Play great, be functional and responsible to not only the music but the people that are around the music, living in the day-to-day life of what it is to be on the road? And that is very hard to find, and whenever I find somebody who can do that, I’m really happy.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny is also a prolific composer—creating work for acoustic and electric instruments including compositions for solo guitar, small groups, and large orchestras. And when he writes for his band—he composes with members of the band in mind, like saxophonist Chris Potter or drummer Antonio Sanchez…

Pat Metheny: I think we all are kind of mandated by the project at hand to offer our best to our, you know, fellow citizens on the bandstand if you’re the band leader. You want to keep people engaged. You want to—you want them to have fun. You want people to be able to utilize their, deeply honed and finely tuned talents to the maximum areas that are their areas of interest and expertise. So yeah, I mean, I’m going to hire Chris Potter, I’m going to write some music that hopefully will meet that description.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: Then it can go a slightly different way, which is I have this bunch of music that I’m really interested in. I want to follow through on what this implies. Who would be the best guys to do that? What do I need? Who do I need? What kind of musician do I need? There’s some of that, too, and I think you always are trying to get the balance of that right in terms of let’s call it casting of musicians. You know, sometimes it’s a little better than others, but mostly, I can say I’ve always had really good bands. I mean, not mostly. I mean, you know, I don’t think there’s but one or two people I’ve ever fired over 40-some years now.

Jo Reed: And that’s with a lot of touring.

Pat Metheny: Yeah. Two, and neither were for musical reasons.

Jo Reed: When you compose, when you’re starting a composition, do you know where you want to go when you begin, or do you find it as you go?

Pat Metheny: You know, the answer which I think is kind of almost universal, which is no. You have no idea, and you have no idea if you’re ever going to write another note. It’s like this mystery zone, and it never happens the same way twice. There is one thing I would say, and I note that a lot of people seem to agree with this. There’s nothing like a deadline to help you focus, and I’ve certainly found myself facing that deadline thing with oftentimes useful results. Sometimes, waiting it out is a good idea. The one thing I do know is that you’ve got to show up, and I when I go into periods where I’m going to be on output that’s kind of the way I think of it. It’s like I’m going to generate some stuff. You know, just sitting there sometimes is not a bad thing. But you’ve got to go. You’ve got to go sit there and wait it out. You can’t not do that and think you’re going to get to something. So I kind of set a fairly rigorous schedule, like okay, I’m going to get up at 4:30 in the morning and I’m going to work from 4:30 until, you know, the kids have to get up to go to school, and I do. And sometimes I get a lot; sometimes I don’t get anything. But I know I was there. To me, I always say it’s a little bit like fishing. It’s sort of like you know, you’ve got to go to the pond, and you might not catch anything, but if you don’t go to the pond, you’re definitely not going to catch anything. The other thing is, if I really am not coming up with anything, I just start. It’s like okay, here’s a chord, and I’ll just play it, and I’ll write it down. It’s like, what does that chord want to do.

Jo Reed: What do you use, a keyboard?

Pat Metheny: I always write on the piano. It’s very—unless it’s going to be a very guitar-intensive thing like a guitar trio record, I’ll utilize the guitar more. But guitar is deceptive for me. Piano I don’t play well, so I’m thinking really just in terms of ideas.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny has been known for his innovative use of emerging technologies, but at the same time, he continues to value highly the sound of acoustic guitar.

Pat Metheny: You cannot beat acoustic sound. I mean, I love playing with amps and everything. There’s nothing cooler than sitting here with an acoustic guitar, with you like that, and hearing an acoustic result of whatever my ideas are.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: It’s way more complex than anything that will ever come out of any speaker, including recordings.

Jo Reed: And that belief motivated the creation of his acoustic, mechanical platform, which became The Orchestrion Project.

Pat Metheny: Yeah, I mean, the [laughs]—The Orchestrion Project, the first thing I usually say about it is that had there been any doubt about how weird I actually am, that project put it to rest once and for all. I think people had their suspicions, but…

Jo Reed: The Orchestrion Project has its roots in the old player piano that his grandfather owned.

Pat Metheny: My grandfather had a player piano in his basement that was fascinating to me. It was like Jules Verne science fiction, but it smelled ancient, and the keys would move by themselves. I mean, it was just fascinating to me. And from then on, I’ve been interested in mechanical musical instruments. It’s been a part of my life as far back as I can remember. Time went on; the piano player companies started to add other things a bass drum, a cymbal, a little marimba. Those were the first orchestrions, the player piano that had other instruments attached. That’s where the name came from. And if you’ve ever heard one of those instruments, including the player piano, you can really just listen to it for about 30 seconds, and then you want to kill yourself because there’s no dynamics. It’s like da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da. And if anybody talks like that, if I were to talk like that all the time, you would – you can’t function with that. And that was a big part of the reason I think why it went away as, let’s call it, an output device. It didn’t really represent music as we know music to be. So my fascination resulted in going to lots of museums and really studying that stuff over the years.

Jo Reed: Pat began to work with a team of instrument makers, technicians, and programmers to create an orchestrion of modified and custom-made instruments that Pat would control from his guitar. In other words, Pat’s notes on the guitar would activate notes in the other instruments – like a giant player piano but as Metheny emphasizes it was acoustic, and it had dynamics.

Pat Metheny: I could, from the guitar, generate all of this material from a guitar that was acoustic in nature. I wasn’t playing synths. I was playing what would happen in a room. The air was moving.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny composed music especially for the orchestrion, cut a record with it and took it out on the road for his first solo tour.

Pat Metheny: I thought, if I ever do a solo concert, I want it to be really something different, and it was at least that.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: I had very short amount of time to, like, record and write and make a record, and then I went out and did 150 gigs around the world with this thing, just standing alone on stage. And I have to say; it was one of the most terrifying and enriching experiences I’ve ever had. I learned so much stuff because there was no place to look; nobody had ever done anything like that. And honestly, now that I’ve done it, and now that I know a lot more stuff, I can’t wait to do it again in four or five years, because now I know the other nine insane inventor people on the planet, because they all came to the gig.

Jo Reed: I bet they did. Pat’s recorded scores of records under his own name and has worked with a diverse group of musicians from David Bowie to Charlie Hayden to Steve Reich to his collaboration with saxophonist Ornette Coleman which resulted in the album Song X that was produced in an inspiring three-day recording session.

<Musical Interlude>

Jo Reed: But despite all his records and the Grammy Awards that went along with them, Pat Metheny still finds recording challenging.

Pat Metheny: In the years that I’ve been kind of active, I’ve made records all different kinds of ways, from, you know, very quickly, four, five, six hours, to spending months on a project. And it’s always dependent on, you know, what your goal is, what is it you’re trying to do, what are you hoping to accomplish, what story do you want to tell with that project. All that said, my relationship to recording has always been difficult – like it’s been with I think many other musicians – which is the idea of being an improviser and documenting a moment in time that will then be listened to over and over and over and over and over again. Is just kind of like—it’s like a square hole and a round peg; they don’t exactly go together. However, you want to preserve the moments. You want to preserve the things that are true. You want to get that vibe. So for me, the process works like, okay, I’ve worked on it, or whatever I’ve had to do, which sometimes is nothing, and it’s done. Then I listen to it constantly. It’s like, man, finally, I made a record that I really like. This is—I love this record. Man, finally. And I listen to it up to the day it’s released, and then I never want to hear it again, and I think it probably sucked. So, this is like a—there’s a lot of lines where the kind of differentiation between like mental illness and talent—it’s a little fuzzy.

Jo Reed: You have won so many awards, including 20 Grammys—bravo—in 10 different categories. You’ve been inducted into the Down Beat Hall of Fame, and now you’re named a 2018 NEA Jazz Master. What does it mean to you to be named an NEA Jazz Master?

Pat Metheny: You know, honestly, all of this is just—it’s overwhelming for me, to tell you the truth. Being named an NEA Jazz Master, I mean it’s something that is just out of the realm of anything that had ever occurred to me. You know, any kind of recognition that has come along, of course, I’m honored and humbled by it, but this is in such a different category in so many ways. You know, I really don’t even have words to describe what the meaning of it is. My focus has always been on just trying to play good and try to deal with the music, and I’ve been lucky to be able to kind of deal in that currency and live in that universe. All I would ever hope to do is to, in a tiny way, express my gratitude, of course, and, how incredibly meaningful it is to me, and what an honor it is to me. And to all of the musicians like me that are all just trying to play good.

Jo Reed: Well, Pat Metheny, thank you so much, and congratulations.

Pat Metheny: My pleasure, thank you.

Jo Reed: That was 2018 NEA Jazz Master, guitarist Pat Metheny. The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert will take place on Monday, April 16, at 8 pm at the Kennedy Center here in Washington DC. For ticket information about this free event, go to arts.gov. And if you can’t make it to DC—don’t despair—we’re live streaming the concert at arts.gov.

You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Please, subscribe to Art Works where ever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on apple—it’ll help people to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.

Music Credit:

“Icefire” composed and performed by Pat Metheny, from the album, Watercolors, used courtesy of ECM and by permission of Songs of Kobalt Music Publishing a/c Pat Meth Music Corp, BMI.

“Walter L” composed by Gary Burton and performed by Burton, Steve Swallow, Pat Metheny and Antonio Sanchez, from the album Quartet Live, used courtesy of Concord Records and used by permission of Grayfriar Music, BMI.

“Missouri Uncompromised” written by Pat Metheny, performed by Pat Metheny, Jaco Pastorius and Bob Moses from the album Bright Size Life. Used courtesy of ECM.

“Airstream,” written by Pat Metheny and Lyle Mays, performed by the Pat Metheny Group. Used courtesy of ECM.

“Geneology” written by Pat Metheny, performed by Pat Metheny and the Unity Group. Used courtesy of Nonesuch.

“One Quiet Night” written and performed by Pat Metheny, from the album One Quiet Night. Used courtesy of Warner Brothers.

“Spirit of the Air,” written and performed by Pat Metheny from the album Orchestrion. Used courtesy of Nonesuch.

“Song X composed by Ornette Coleman and performed by Metheny, Coleman, Haden, D. Coleman and Jack Dejohnette, from Song X, used courtesy of Nonesuch/WBR and used by permission of Phrase Text Music a/c Songs of Kobalt Music Publishing , ASCAP.

<Music>

Jo Reed: You’re listening to 2018 NEA Jazz Master, guitarist and composer, Pat Metheny and this is Art Works the weekly podcast from the National Endowment for the Arts. I’m Josephine Reed.

It’s no exaggeration to say that Pat Metheny reinvented the traditional sound of jazz guitar. Whether playing his own compositions or one of his wildly inventive improvisations, Pat Metheny shows a deep musicality while pushing the boundaries of jazz guitar. He is one of the few artists who has achieved crossover popularity with three gold records as well as critical acclaim. Over the course of his career, Pat Metheny has won 20 Grammys in ten different categories. And in 2013, He became only the fourth guitarist inducted into the DownBeat Hall of Fame.

Pat Metheny’s music resists an easy description, he casts a wide musical net, from modern jazz to rock to country to classical. He cut his teeth as a teenager playing with jazz musicians in Kansas City. He joined Gary Burton’s band when he was 20, cut his debut album at 21 and began The Pat Metheny Group at the tender age of 23. And he’s never looked back. From that first album Bright Size Life to present day, Pat Metheny continues to push the music and reshape the possibilities for jazz guitar for both players and fans. I spoke with Pat Metheny in a New York rehearsal space—so you’ll occasionally hear the sound of traffic and sirens. Throughout the conversation, Pat recounted the significance of his musical influences throughout the years….beginning the small Missouri town where he was raised.

Pat Metheny: Well, I was born in Kansas City, Missouri, grew up in a very small town called Lee’s Summit. The thing of growing up out there has been something that I’ve always tried to represent. You know, just the nature of the landscapes out there, there was like, a lot of space. But more specifically, the nature of the sound out there. That’s been a part of my life from the ground up. That’s a sound that I know. It’s been a source of material and inspiration for me.

Jo Reed: You grew up in a musical household, didn’t you?

Pat Metheny: I was lucky to be a member of a family where music was kind of a central thing. I mean, my older brother Mike––fantastic trumpet player, almost like a child prodigy kind of guy. My dad was a very good amateur trumpet player, and my mom’s dad was a professional trumpet player, so trumpet was everywhere. And me, too; I started on the trumpet when I was eight. The trumpet thing has remained kind of a constant for me. I mean, even now, when I’m playing, you know, on the guitar, I’m kind of thinking trumpet. So it’s real deep, that trumpet thing for me, and I would list among my most important influences trumpet players. Certainly, Miles Davis is, like so many people, probably the major reason that I’m even involved in this general area of music. Hearing one of his records when I was about 11 changed my life. It was like somebody hitting me over the head with a baseball bat, like, what is that? You know, it should be noted I was a terrible trumpet player. I often joke that when I would play a note, birds would drop from the sky, you know. It was really bad, and it was a good move to get off that act and go someplace else.

Jo Reed: Now, why the guitar? What was it about the guitar that just grabbed you?

Pat Metheny: Well, I’m chronologically right at that spot where the guitar sort of became more than just an instrument. It was almost an iconic example of something that was happening in the culture that signified this big change that was just about to go down. You know, I think I responded to that, to the way a eight- or nine-year-old kid would when, like, a billion other people, I saw the Beatles on the Ed Sullivan Show, and suddenly, that instrument had a place in my consciousness that just, it did not before. Where my story is a little different is that not long after that is when I heard this first Miles Davis record, and I went completely there. It seemed to me that the music really established what the culture was about to become. To me, there was something about that, that it was like something is about to happen—more than an electric guitar, it was that.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny started playing with other jazz musicians in Kansas City when he was a teenager. His role model in those early years, the legendary Wes Montgomery.

Pat Metheny: Wes is still, hands down, one of the major musicians in my life. I think that there’s a normal trajectory that many young musicians follow, which is you have a few favorite players. You know, you emulate them to a degree, best of your ability early on, and Wes was the guy for me, no question. The first year I played, I played with my thumb, and when I would do the octave kind of thing as a young kid, on the gigs that I was lucky to find myself on, people would respond to that. And yet, at the same time, I was kind of hyper-aware of, you know, how that was kind of a violation of what actually the music represents, which is a certain kind of personal honesty and personal authenticity of being who you are. And when I think about every one of my favorite players – the people that I find myself responding to the most – are the people who are able to capture the things that they really love about music, and represent them in a way that, given my interests, fulfill a certain musical level of content. But beyond that, show something about who they are, where they’re from, what they love in music, and all the different ways that music can come to have meaning. So yeah, kind of early on, I realized whenever I would go into my Wes thing, I was not really honoring that mandate. And, maybe it’s, to me, one of the under-reported glories of this form is that it doesn’t just ask that you bring who you are to the thing; it demands it. The musicians who have really been able to contribute are people who bring something kind of their own design that comes out of who they are in a way that’s really true, and I’ve really tried to get to that.

Jo Reed: It’s no easy thing developing musical chops and creating a style that’s unique and authentic—to honor the traditions but keep pushing the music forward. Pat worked hard, even demonically on the guitar. No question about that, but his approach to the music is deceptively simple.

Pat Metheny: The way music has unfolded for me has been primarily built on just being a fan of music, loving music. Which as far back as I can remember, I was constantly involved with trying to understand what music is and how it works. And the next stage for me, if there’s something I really love, it’s how did they do that. What is involved in making that sound happen? And, kind of across the board, I mean, again, regardless of how you want to place it on a stylistic spectrum, the music that I feel like I’ve offered over the course of all this time has been a real reflection of what I love as a fan. I mean, if you look at the musicians I’ve worked with, that’s pretty much also the same list of musicians who are my favorite musicians as a fan. And, you know, when I think about Gary Burton, I was such a fan of that music fairly early going, I was like okay, so how do those tunes work? How are they put together? I think through understanding; you start to garner a certain wisdom about things, how it all goes together, that with the key element of being around a lot of good musicians, which I’ve always been very fortunate, to this day, to be able to say that I am. You have a chance of maybe getting to something. But it’s really difficult, you know? There’s one thing that doesn’t really get discussed that much, which is music is really hard. It’s hard to be a musician – and at the level that we’re talking about – and especially year after year after year after year after year, to maintain even on an aspirational level. That standard is something that is both incredibly difficult, but also, the greatest possible way to go through life because you learn so much about so many things by understanding music. In my case, I could probably be considered functionally illiterate, based on the fact that getting interested in the music that manifested itself in practicing 10 or 12 or 14 hours a day, every day. And as a result, starting in sixth grade, I never took a book home. I mean, the fact that they let me graduate from high school was like a mercy graduation. But, along the way, I learned about science, math, history -- everything through music.

Jo Reed: Let’s talk about Gary Burton. How did you meet, and how did you join his band?

Pat Metheny: Gary is such an important, huge figure for me in so many ways, I mean, starting with the fact that that band, the Gary Burton Quartet of the late ‘60s that was like the Beatles for me. That was the band that somehow seemed to have their finger on the pulse of that moment within the realm of improvised music that was unlike anything else. I think their well noted for that as well. Beyond that, the particulars of the language that Gary was addressing were especially resonant to me in the sense that it was kind of a rhythm section band. You know, there wasn’t a piano player. The guitar was almost functioning in the role of a horn player. And, you know, when I heard those records, I just couldn’t get enough of them and followed that band really closely.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: I had played the Wichita Jazz Festival a couple times when I was, you know, a really young teenager. And the woman that ran the Wichita Festival got in touch with me, I was already teaching at the University of Miami at that point, and said they were going to bring Gary to be in the festival. And when I heard Gary was going to be there, I was like, definitely, I’ll come up for that. When I got there, there’s Gary Burton, and it had kind of been arranged. I would play on that set too because he wasn’t there with the band. And, you know, so he’s there at the rehearsal with all these people and there’s a tune of Gary’s called Walter L that I started playing when I was maybe 14 or 15 years old. And the band director guy, who I knew, said “well, what do you want to play?” And I said, “well this tune, Walter L.” So me and the rhythm section started playing it, which of course caught Gary’s attention, because it’s not a easy kind of a tune; it’s a kind of weird tune. It would be like if somebody started playing one of my really difficult tunes, I would notice it. So he started playing with us, and we played this tune, and it was like, you know, a dream come true for me to just hear that. And then the band director said okay, well you guys will play, you know, the big band stuff with Gary. And that was the first time I got to play with Gary. He was very nice. He came and heard my set and gave me a lot of compliments mixed with criticisms, as became the thing with us over those next few years, very valuable criticism, too. But as I mentioned, at that time, I was teaching at the University of Miami. He was giving me the rap about, you know, maybe you should think about moving to New York, he said, “Or maybe you should move to Boston,” you know, “As kind of an in-between thing, would you like to teach at Berklee?” And I was like, “Sure.” So I came up to Boston, really thinking maybe if I get to Boston, maybe he’ll hire me and I can be in the band, and that’s exactly what happened. Yeah, from that point forward, I continued to play with Gary for another two and a half years, or two years, and every night was an amazing experience for me to just hear him, not to mention Steve Swallow, who I would put right there with Gary as a major, major influence for me.

Jo Reed: I just have to ask you to go back very quickly, because you say you were practically functionally illiterate, yet you were teaching at the University of Miami.

Pat Metheny: That’s one of those things that looks really great in the press kit. It wasn’t nearly as dramatic as that. It’s hard to even imagine this, but in 1972, the electric guitar was not considered an actual instrument. The University of Miami decided that they were going to have an electric guitar program. The dean of the University of Miami, Dr. Bill Lee, came and kind of recruited me like somebody would recruit a football player, which I have to say, for my parents, that was the happiest day of their entire lives. So I go to the University of Miami and within a week or two, I realized, you know, I’m not going to be able to pull this off. And also, I’m playing with all these great musicians, because it was a weird kind of moment that happens every now and then, where a bunch of really talented people all kind of wound up there. And so I want to Dr. Lee, and I was like, “Dr. Lee, thank you, but you know, I really can’t do this.” And as it happened, because they had opened up the electric guitar program that semester, they were expecting six electric guitar players, of which I was going to be one. They had 80, and one teacher. And it was, like, kind of a crisis. And because I had, at that point, played, you know, for four or five years almost I was, you know, a kind of a professional musician, I guess you could say. So he asked me if I would teach, which I said, “Can I stay in my dorm room and teach?” And he’s like, “Yeah.” And so, I no longer was a student, but I taught for two more semesters, and then started teaching at Berklee for two more semesters there, and then moved on to just playing all the time.

Jo Reed: While Pat was all of 21 and playing with Gary Burton, he recorded his debut album—Bright Size Life on Manfred Eicher’s ECM label.

Pat Metheny: The mind of ECM, Manfred Eicher, heard me on the first Gary Burton record in 1974, and offered me the opportunity to do a record. Gary being Gary said, “You’re not ready to do a record. You might only get to do one record in your whole life, so you better make sure that it’s THE record.” And in retrospect, I realized he was right, but at the time, I was like I want to do it now, you know. But his wisdom prevailed, so I did wait––I mean, it was a year and a half, as I think about it now; it seemed like 20 years at the time––to, you know, really write that bunch of tunes that became the tunes on Bright Size Life. That, you know, are arguments that I still feel are valid arguments. I could play every tune on that record right now, and I still can sort of say yeah, that’s talking about stuff that’s important to me. And I’m not sure I would have done that a year and a half before then, and I do have to really give Gary a lot of credit for that.

<Musical Interlude>

Jo Reed: After playing with Gary Burton for three years, Pat decided to strike out on his own and form the Pat Metheny Group—which was a daring move on his part, since he was very young and very broke.

Pat Metheny: Honestly, happened way faster than I ever would have expected that I became a leader. I was interested in dynamics. And I was interested in long-form development and a kind of band sound that was not about backbeats but more about the kinds of almost orchestrational elements that I didn’t see anybody else doing. You know, I think I had run a poll or some—or two, maybe, around that time, and so there was a lot of interest. I just kind of said okay. I just kind of went with it. I had met some really talented younger musicians who were ready to go, and I took the money I had saved from my paper route as a kid in Lee’s Summit and bought a van from my dad, and we were like the Blues Brothers. We were, like, on a mission from God and played every gig you could possibly play in the United States, and in that three years, put almost 300,000 miles on that van, with no roadie or crew for the first two years. Yeah, I mean, that was kind of the way it went. And back then, it was not really that different than now. It’s like the only thing you can really do with this music is go out and play, because there’s no real natural audience for any of this. You know, people often say, like wow, it must’ve been so great in—back then. It was impossible then the same way it’s impossible now. The only thing you can do is go out and play. And, you know, I think that if you have something to offer, that music is impervious to anything. And I’ve always built on that as a truth.

Jo Reed: The Pat Metheny Group first album was Watercolors, and they were off to the races…

Pat Metheny: Man, nobody was more surprised than me about that. People didn’t sell large numbers of records back then. And it wasn’t like I was trying to do that. I mean, the tunes on that first group record were 12 and 13 minutes long. It wasn’t like oh, let’s make some radio-friendly tunes here. But it sold, I mean, you know, hundreds and hundreds of thousands of records and not just a little bit of that was because of the amount of gigs we were doing. We were out there playing all the time. It was mystifying to me, and yet at the same time, it kept going. I mean, I did a solo guitar record after the first group record called New Chautauqua that was even more successful than that first group record. And then comes American Garage, which was, you know, at that same level.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: Again, I have to put a lot of the weight of why that is to the amount of gigs that I’ve done. I mean, you know, everybody knows the numbers of—you know, I mean, there’s probably not too many people you could find over the last 40 years that would have a number higher than mine in terms of gigs played.

Jo Reed: Pat’s closet collaborator in the group was without doubt keyboardist Lyle May—Lyle May was co-composed many of the tunes with Pat and also provided orchestrations and arrangements for the band. With that six-sense many musicians have, Pat knew Lyle would be a great partner before they even played together.

Pat Metheny: Well, I heard Lyle. You know, I’d already made Bright Size Life, had, you know, been playing with Gary for a few years. Lyle was to play on a Wichita Jazz Festival, and I was coming back to play with Gary on that same festival. So I went, and I heard his concert, and it was fantastic, and I realized right away, like, man, I could play with this guy. I know I could play with him. With Lyle, I could tell he was listening. He could really listen to the cats he was playing with. That’s what it all is, anyway, is listening. It’s not even playing; just listening. And I was like man, this guy can really listen, and he could play. And then we started playing, and that became the band. Lyle is an incredible musician, one of the most amazing musicians I have ever known. We can just play together, and I’ve experienced that with, not a lot, but a few musicians over the years, Charlie Haden and I were like that. There’s just some people you meet, and you’re like one right away. And you know, Lyle’s one of those few people for me, no question.

Jo Reed: Now, because you tour so much it means you’re playing out constantly. Choosing the musicians you play with becomes so much more important because obviously, you don’t want anybody to be mailing this in night after night after night. So how do you choose who you play with?

Pat Metheny: It’s a really good question, difficult to answer. I mean, of course, a lot of it, for me, kind of depends on, what story you want to tell at that particular moment. And there are certain people who would be, you know, cast perfectly to tell this story who would be terrible to tell that story, and so forth. Because the range of interests that I have as a musician is so wide, it’s always been difficult for me to find people who can just hang. And one other quality of my thing, it turns out, is that there’s a kind of deceptive simplicity to it all. It sounds like, that doesn’t seem like that would be that hard. But actually, those tunes are pretty hard. I mean, I’ve watched a lot of really hardcore beboppers crash and burn on the bridge to James, and there’s a lot of tunes like that. But the larger issue becomes something that has nothing to do with music, which is, you know, can that person hang, as a person, night after night after night after night after night, and be cool. Play great, be functional and responsible to not only the music but the people that are around the music, living in the day-to-day life of what it is to be on the road? And that is very hard to find, and whenever I find somebody who can do that, I’m really happy.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny is also a prolific composer—creating work for acoustic and electric instruments including compositions for solo guitar, small groups, and large orchestras. And when he writes for his band—he composes with members of the band in mind, like saxophonist Chris Potter or drummer Antonio Sanchez…

Pat Metheny: I think we all are kind of mandated by the project at hand to offer our best to our, you know, fellow citizens on the bandstand if you’re the band leader. You want to keep people engaged. You want to—you want them to have fun. You want people to be able to utilize their, deeply honed and finely tuned talents to the maximum areas that are their areas of interest and expertise. So yeah, I mean, I’m going to hire Chris Potter, I’m going to write some music that hopefully will meet that description.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: Then it can go a slightly different way, which is I have this bunch of music that I’m really interested in. I want to follow through on what this implies. Who would be the best guys to do that? What do I need? Who do I need? What kind of musician do I need? There’s some of that, too, and I think you always are trying to get the balance of that right in terms of let’s call it casting of musicians. You know, sometimes it’s a little better than others, but mostly, I can say I’ve always had really good bands. I mean, not mostly. I mean, you know, I don’t think there’s but one or two people I’ve ever fired over 40-some years now.

Jo Reed: And that’s with a lot of touring.

Pat Metheny: Yeah. Two, and neither were for musical reasons.

Jo Reed: When you compose, when you’re starting a composition, do you know where you want to go when you begin, or do you find it as you go?

Pat Metheny: You know, the answer which I think is kind of almost universal, which is no. You have no idea, and you have no idea if you’re ever going to write another note. It’s like this mystery zone, and it never happens the same way twice. There is one thing I would say, and I note that a lot of people seem to agree with this. There’s nothing like a deadline to help you focus, and I’ve certainly found myself facing that deadline thing with oftentimes useful results. Sometimes, waiting it out is a good idea. The one thing I do know is that you’ve got to show up, and I when I go into periods where I’m going to be on output that’s kind of the way I think of it. It’s like I’m going to generate some stuff. You know, just sitting there sometimes is not a bad thing. But you’ve got to go. You’ve got to go sit there and wait it out. You can’t not do that and think you’re going to get to something. So I kind of set a fairly rigorous schedule, like okay, I’m going to get up at 4:30 in the morning and I’m going to work from 4:30 until, you know, the kids have to get up to go to school, and I do. And sometimes I get a lot; sometimes I don’t get anything. But I know I was there. To me, I always say it’s a little bit like fishing. It’s sort of like you know, you’ve got to go to the pond, and you might not catch anything, but if you don’t go to the pond, you’re definitely not going to catch anything. The other thing is, if I really am not coming up with anything, I just start. It’s like okay, here’s a chord, and I’ll just play it, and I’ll write it down. It’s like, what does that chord want to do.

Jo Reed: What do you use, a keyboard?

Pat Metheny: I always write on the piano. It’s very—unless it’s going to be a very guitar-intensive thing like a guitar trio record, I’ll utilize the guitar more. But guitar is deceptive for me. Piano I don’t play well, so I’m thinking really just in terms of ideas.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny has been known for his innovative use of emerging technologies, but at the same time, he continues to value highly the sound of acoustic guitar.

Pat Metheny: You cannot beat acoustic sound. I mean, I love playing with amps and everything. There’s nothing cooler than sitting here with an acoustic guitar, with you like that, and hearing an acoustic result of whatever my ideas are.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: It’s way more complex than anything that will ever come out of any speaker, including recordings.

Jo Reed: And that belief motivated the creation of his acoustic, mechanical platform, which became The Orchestrion Project.

Pat Metheny: Yeah, I mean, the [laughs]—The Orchestrion Project, the first thing I usually say about it is that had there been any doubt about how weird I actually am, that project put it to rest once and for all. I think people had their suspicions, but…

Jo Reed: The Orchestrion Project has its roots in the old player piano that his grandfather owned.

Pat Metheny: My grandfather had a player piano in his basement that was fascinating to me. It was like Jules Verne science fiction, but it smelled ancient, and the keys would move by themselves. I mean, it was just fascinating to me. And from then on, I’ve been interested in mechanical musical instruments. It’s been a part of my life as far back as I can remember. Time went on; the piano player companies started to add other things a bass drum, a cymbal, a little marimba. Those were the first orchestrions, the player piano that had other instruments attached. That’s where the name came from. And if you’ve ever heard one of those instruments, including the player piano, you can really just listen to it for about 30 seconds, and then you want to kill yourself because there’s no dynamics. It’s like da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da, da-da-da-da. And if anybody talks like that, if I were to talk like that all the time, you would – you can’t function with that. And that was a big part of the reason I think why it went away as, let’s call it, an output device. It didn’t really represent music as we know music to be. So my fascination resulted in going to lots of museums and really studying that stuff over the years.

Jo Reed: Pat began to work with a team of instrument makers, technicians, and programmers to create an orchestrion of modified and custom-made instruments that Pat would control from his guitar. In other words, Pat’s notes on the guitar would activate notes in the other instruments – like a giant player piano but as Metheny emphasizes it was acoustic, and it had dynamics.

Pat Metheny: I could, from the guitar, generate all of this material from a guitar that was acoustic in nature. I wasn’t playing synths. I was playing what would happen in a room. The air was moving.

Jo Reed: Pat Metheny composed music especially for the orchestrion, cut a record with it and took it out on the road for his first solo tour.

Pat Metheny: I thought, if I ever do a solo concert, I want it to be really something different, and it was at least that.

<Musical Interlude>

Pat Metheny: I had very short amount of time to, like, record and write and make a record, and then I went out and did 150 gigs around the world with this thing, just standing alone on stage. And I have to say; it was one of the most terrifying and enriching experiences I’ve ever had. I learned so much stuff because there was no place to look; nobody had ever done anything like that. And honestly, now that I’ve done it, and now that I know a lot more stuff, I can’t wait to do it again in four or five years, because now I know the other nine insane inventor people on the planet, because they all came to the gig.

Jo Reed: I bet they did. Pat’s recorded scores of records under his own name and has worked with a diverse group of musicians from David Bowie to Charlie Hayden to Steve Reich to his collaboration with saxophonist Ornette Coleman which resulted in the album Song X that was produced in an inspiring three-day recording session.

<Musical Interlude>

Jo Reed: But despite all his records and the Grammy Awards that went along with them, Pat Metheny still finds recording challenging.

Pat Metheny: In the years that I’ve been kind of active, I’ve made records all different kinds of ways, from, you know, very quickly, four, five, six hours, to spending months on a project. And it’s always dependent on, you know, what your goal is, what is it you’re trying to do, what are you hoping to accomplish, what story do you want to tell with that project. All that said, my relationship to recording has always been difficult – like it’s been with I think many other musicians – which is the idea of being an improviser and documenting a moment in time that will then be listened to over and over and over and over and over again. Is just kind of like—it’s like a square hole and a round peg; they don’t exactly go together. However, you want to preserve the moments. You want to preserve the things that are true. You want to get that vibe. So for me, the process works like, okay, I’ve worked on it, or whatever I’ve had to do, which sometimes is nothing, and it’s done. Then I listen to it constantly. It’s like, man, finally, I made a record that I really like. This is—I love this record. Man, finally. And I listen to it up to the day it’s released, and then I never want to hear it again, and I think it probably sucked. So, this is like a—there’s a lot of lines where the kind of differentiation between like mental illness and talent—it’s a little fuzzy.

Jo Reed: You have won so many awards, including 20 Grammys—bravo—in 10 different categories. You’ve been inducted into the Down Beat Hall of Fame, and now you’re named a 2018 NEA Jazz Master. What does it mean to you to be named an NEA Jazz Master?

Pat Metheny: You know, honestly, all of this is just—it’s overwhelming for me, to tell you the truth. Being named an NEA Jazz Master, I mean it’s something that is just out of the realm of anything that had ever occurred to me. You know, any kind of recognition that has come along, of course, I’m honored and humbled by it, but this is in such a different category in so many ways. You know, I really don’t even have words to describe what the meaning of it is. My focus has always been on just trying to play good and try to deal with the music, and I’ve been lucky to be able to kind of deal in that currency and live in that universe. All I would ever hope to do is to, in a tiny way, express my gratitude, of course, and, how incredibly meaningful it is to me, and what an honor it is to me. And to all of the musicians like me that are all just trying to play good.

Jo Reed: Well, Pat Metheny, thank you so much, and congratulations.

Pat Metheny: My pleasure, thank you.

Jo Reed: That was 2018 NEA Jazz Master, guitarist Pat Metheny. The 2018 NEA Jazz Masters Tribute Concert will take place on Monday, April 16, at 8 pm at the Kennedy Center here in Washington DC. For ticket information about this free event, go to arts.gov. And if you can’t make it to DC—don’t despair—we’re live streaming the concert at arts.gov.

You’ve been listening to Art Works produced at the National Endowment for the Arts. Please, subscribe to Art Works where ever you get your podcasts and leave us a rating on apple—it’ll help people to find us. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.