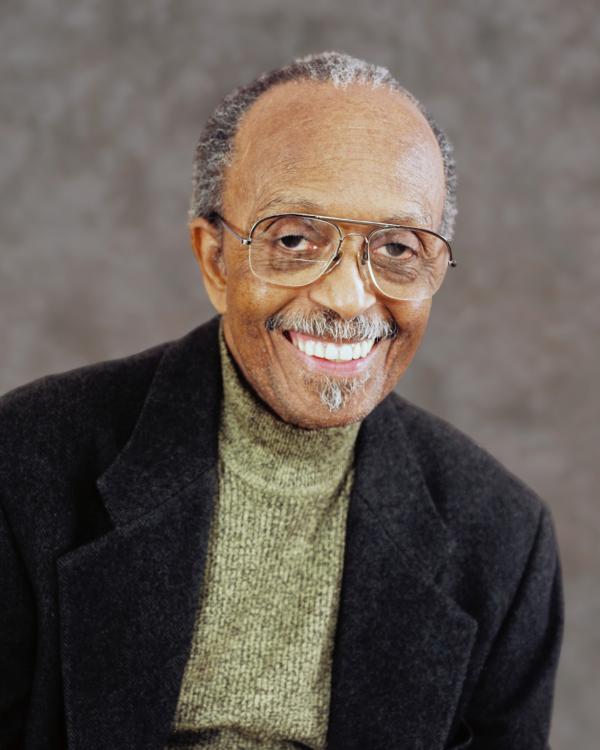

Jimmy Heath

Photo by Tom Pich/tompich.com

Bio

"I am humbled to be included among the great musicians in our American history. I express my gratitude to these Jazz Giants, many of whom were close friends, who shaped this great American art form called Jazz and ultimately helped to shape my life as well. I thank the NEA committee for recognizing America’s Jazz Masters and the Art of Jazz itself and I am honored and privileged to be a part of this legacy."

The second of the illustrious Heath Brothers to receive an NEA Jazz Master Fellowship (bassist Percy received the award in 2002), Jimmy was the first Heath to choose music as a career path. Starting on alto saxophone (and acquiring the nickname "Little Bird" due to the influence Charlie "Yardbird" Parker had on his style), one of his first professional jobs came in 1945-46 in the Midwest territory band led by Nat Towles, out of Omaha, Nebraska. Returning to Philadelphia, he briefly led his own big band with a saxophone section that included John Coltrane and Benny Golson—also products of the city's jazz scene. Gigs followed with Howard McGhee in 1948 and with Dizzy Gillespie's big band from 1949-50.

In the early 1950s, Heath switched to tenor sax, playing with Miles Davis in 1953 and then again briefly in 1959, among other gigs. In the 1960s, he began his own recordings as a leader, and frequently teamed up with Milt Jackson and Art Farmer. By that time he had honed his talent as a composer and arranger, creating such widely performed compositions as "Gingerbread Boy" and "C.T.A." By combining his versatile style of performing and his outstanding writing and arranging abilities, he set a high standard of accomplishment in the jazz field. He made more than 100 recordings and composed more than 100 original works.

As an educator, Heath taught at Jazzmobile, Housatonic Community College, City College of New York, and Queens College, where he retired from full-time teaching in 1998. He held honorary degrees from Sojourner-Douglass College and the Juilliard School, and had a chair endowed in his name at Queens College.

Beginning in the mid-1970s, Jimmy teamed up with brothers Percy and Albert "Tootie" as the Heath Brothers, a band which also at times included contributions from Jimmy's son, the noted percussionist, composer, and rhythm-and-blues producer, Mtume. In addition, he had performed with other jazz greats, such as Slide Hampton and Wynton Marsalis, and indulged in his continuing interest in the dynamics of arranging for big band. In 2010, his memoir, I Walked with Giants, was published. He remained active as an educator, saxophonist, and composer until his passing.

Selected Discography

Really Big!, Riverside/OJC, 1960

On the Trail, Riverside/OJC, 1964

Little Man, Big Band, Verve, 1992

Heath Brothers, Jazz Family, Concord, 1998

Turn Up the Heath, Planet Arts, 2006

Interview by Molly Murphy for the NEA

January 13, 2007

Edited by Don Ball, NEA

CHOOSING THE INSTRUMENT

Q: Many musicians seem like they had a couple of really pivotal experiences when they were young -- what are some of yours?

Jimmy Heath: I always had music in my home because my mother and father had all of the recordings that were called "race records" at the time, and others. My household was full of music -- jazz was played in my house at all times, and gospel and a little western classical music. And my father played the clarinet, my mother sang in the church. They inspired each of us children to play an instrument of our choice.

I played alto saxophone because I had heard people like Johnny Hodges and Benny Carter on those recordings. They really captured my fancy. I eventually heard Charlie Parker after I had started playing. I figured out I didn't have a sound like Johnny Hodges so I decided maybe I could play bebop when it came in.

Q: So you approached the mountain instead of the molehill, from the get go.

Jimmy Heath: You know, Johnny Hodges was one of the greatest singers of all time, including vocalists.

Q: So when you say, "singers," do you mean on his horn?

Jimmy Heath: Yes. He made the instrument sing.

Q: And you picked up on that as a kid?

Jimmy Heath: Yeah, I heard it. My father gave me a saxophone at 14 and I've been stuck with it ever since.

Q: What are some of the challenges of the instrument? What are some of the great things? Why do you love saxophone?

Jimmy Heath: Well, the saxophone has a voice quality. If you're playing a soprano it's a feminine sound, if you're playing the tenor it's more masculine. The alto was my first choice because of the people that I had heard playing it so well. The saxophone is a very communicating instrument, it has a string-like quality. You can play the saxophone like Ben Webster who plays the tenor like it's a cello. It has a very lyrical possibility when you play. The brass instruments are kind of harsh although, when they put the mutes in, they get beautiful. There's some sonority about the brass instruments that is cool. But I just fell in love with the saxophone as a kid.

Q: Why then did you switch to tenor? Were you looking for that bigger, richer sound?

Jimmy Heath: When I got back to Philadelphia after the war, World War II, the fourth person hired for the gig was the tenor saxophone -- trumpets and trombones and altos wouldn't get the gig. So if there was a rhythm section, the fourth instrument hired around town was a tenor. So I went to the tenor for commercial reasons. And because I was playing so much of Charlie Parker's lyrics that people were calling me "Little Bird." So I said, "Well, maybe, if I play a tenor, I could play these same lyrics, and I wouldn't be called,'‘Little Bird' all the time. I would be called, ‘Jimmy Heath.'" I still play "Big Bird's" music because changing the instrument doesn't change your concept. It's still bebop on the tenor saxophone.

People like Lester [Young] and all of them had made the tenor, so it's such an important voice. Coleman Hawkins, Ben Webster, Don Byas. Dexter [Gordon] and Sonny Stitt had played bebop on the tenor so well. Even Charlie Parker played some things on tenor in his inimitable style.

HEATH'S SOUND

Q: When you were trying to develop your own sound, what were you trying to achieve?

Jimmy Heath: You always have an idol or somebody that you're trying to sound like. But it evolves into your own sound, and it takes awhile. All the young students try to play like Coltrane, but nobody can play like Coltrane. He has a personal sound. You have to develop your own personal sound. I found that when I go back to play alto, I don't have the sound I had. I had a nice sound on alto, too, but the tenor and the soprano are my babies now.

Q: Do you think a musician's sound reflects his or her character? Is it like their personality or the way that they verbally communicate?

Jimmy Heath: I think so. If you're an aggressive person, it comes out in your music. If you're romantic, if that's your nature, you'll have that passionate kind of a sound. Any emotion can be translated through the music. But I always refer to my buddy Trane, when we were coming up around Philly. He ended up with a sound in the high register of his horn that was not violent. He could play ballads in the top register of his horn with what I'd call a cry, but not a beg. Like he's crying for something, but not begging like a baby. He's crying with an ethereal kind of heavenly sound. You know, he had so much technique he could play all over the horn, but I still relate to his ballad playing. And to people like Ben Webster and Don Byas on tenor. Dexter was a driving, swinging tenor player. When you hear all these different sounds you incorporate all of them. You put them in the pot, mix it all up, and you come out with your own sound. Just out being yourself and playing for a while. It evolves into your own sound.

Q: I was talking to Billy Taylor yesterday about ballads in particular, that to effectively play a ballad you have to have some emotional depth as a person and the courage to make yourself vulnerable.

Jimmy Heath: I'm like Ben Webster in that I would like to know the lyric of a song and try to interpret the lyric. And if you're playing, "Lover Man," if you know the words, say, "I don't know why, but I'm feeling so sad," that makes you bend that note so sad. You get these inflections in your playing that are sympathetic to the language. And that's why Johnny Hodges and Ben Webster are the greatest ballad players.

THE BIG BAND

Q: When did you start composing and arranging?

Jimmy Heath: I was in a band in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1945, when I got out of high school. Playing in a big band and in the saxophone section, I was surrounded by all of those sounds. And I just began to absorb what the saxophone section should sound like and why it sounded like it did. I copied things off arrangements that we had in the band. Putting all those sounds together made me want to be able to do that, to reproduce big band music because that was the thing that was happening, the big bands. I used to go the Earl Theatre in Philadelphia and see all the big bands. I went to see the [Count] Basie band, I went to see Duke [Ellington], I went to see Jimmy Dorsey. I went to see Tommy Dorsey when he had Frank Sinatra singing, "I'll never smile again." I just loved the big band. When I was about 15 or 16, I went to hear The Glen Miller band. When they put the blue lights on the saxophone section and they played, "Serenade in Blue," I was in heaven. And I said, "That's what I want to do, and that's where I want to be, on the stage playing beautiful music." In fact, I still have a CD of "Serenade in Blue." And I still have things of Jimmy Dorsey. I still got big band stuff I love. Jimmy Lunceford's band, which people don't talk about much, was one of the greatest. He was Duke's competition as far as being intellectually advanced and syncopated in the Afro-American feeling. Jimmy Lunceford was a very special band. Incorporating all of that and then hearing it in my pad with my mother and father, I just got hooked on the big bands. So I started one of my own. And that was a historical band because we were a feeder band into Dizzy Gillespie's band.

The big band is jazz music's symphony orchestra. We can take soloists. We can have duos, trios, quartets, quintets, sextets, septets, and the whole works from a big band. When we get 16 people and you got four trombones, four trumpets, five reeds, and a rhythm section -- heaven.

I made one big band recording called "Little Man, Big Band" that was produced by Bill Cosby on Verve. We got nominated for a Grammy.

Q: When did you make that recording?

Jimmy Heath: '92 or something like that. When the NEA Jazz Masters award came my way in Toronto -- that was the year Elvin Jones, Abbey Lincoln, and myself got the award -- they gave me 20,000 bucks. I took the 20,000 bucks and made half of the latest recording that I have out now called Turn Up the Heath. Planet Arts, the company that put the recording out, paid the other half. So I used my National Endowment money to put out another big band recording.

Q: But it gets harder and harder to get that together in this day and age with people's schedules and the cost of all of it.

Jimmy Heath: The problem is transportation. That's the only reason we don't have big bands -- getting there. It costs you more to get there on an airplane. See we used to travel by buses on the road. When we were on the road, it was fun.

TRAVELING WITH DIZZY

Q: Will you tell me a road story from Dizzy?

Jimmy Heath: Well, OK, one story. We went to Little Rock, Arkansas, before Faubus [Orval Faubus, segregationist governor of Arkansas] in 1949. Trane and I, and Paul Gonzalez was the tenor player. We were in the saxophone section with Dizzy's band. When we got to Little Rock, the people seemed to have scouts, they sent people out to hear what we were playing before they went back to the neighborhood and told people. When we started warming up and all that stuff, people came and listened, and a guy said, "What are y'all playing? All them bebops and stuff? Why don't you go back and send Buddy Johnson or Count Basie down here." They wanted dance music and Dizzy realized that. That night we could have beat the audience up in a fight -- there were more of us on the stage than them! So Dizzy pulled out the hardest music that he thought we didn't know or couldn't play, those five-four pieces that he had. He pulled that out and we made it through it. But he was very disappointed that we couldn't draw people in the southern parts of the country. If we played in the big cities, we were cool. Bebop was hip. Everybody would come and hear this new sound.

Q: People eventually came, right?

Jimmy Heath: Oh no. Never came to that. I think bebop was a little too intellectualized and too fast for people to dance to. You had to be a very good dancer, not one who stands on the floor and poses and shakes their booty and looks at each other. You had to dance in rhythm. So I think a lot of good dancers could dance in cut-time, jitterbug, and half-time it. The tempo would be way up -- they could cut it down and still find their groove.

Q: Do you miss that camaraderie that you had on those days?

Jimmy Heath: Definitely. But right now, with the Dizzy Alumni Band that I've been playing with, we have it again. And it's like school. We have so many talented, young people in that band who never played with Dizzy, but they love him. And they love the music of that generation. And it's still here. It's always a pleasure to be on the bus or traveling with a group of people like that. It's a great experience every night.

EDUCATING THE YOUTH

Q: I want to ask you about education because you've been so involved in jazz education for so long.

Jimmy Heath: Well, jazz has never been easy. It's never been the favorite music of the world. Popular music is usually a little more simplified and jazz is complicated. One of the problems is if the public was more educated musically, if they heard it when they were kids, they would understand it. See, what you hear or see is what you like. And they don't see or hear enough of it to pay it any attention. It just sounds like a bunch of notes and a bunch of guys practicing. There's something about this that the jazz musicians have to realize and try to come to a happy medium or compromise with the people. People haven't practiced chords and scales all day like we have for years, so how are they going to understand all of this?

You know, when you're talking about Western classical music, it's subsidized by the big corporations and the government and everybody but there ain't no kids going to hear that. The young people want entertainment. And you know, they are really it because we're not gonna be here long. They want to have some fun now, everything is about instant gratification. So now we have that problem to solve.

I think the young educated jazz players have to go out and create a market for themselves. Even if they compromise with some of the music that's popular, even if they go to bars or clubs and ask the man, say, "Look, let me bring in a trio on the weekend and see what we can do. We may be able to build it into something." You have to be enterprising. You have to be a marketer now, you have to market yourself. At the same time they're studying jazz and everything's cool, all the schools are teaching it, there are other people studying marketing. They've got to hook up with one of those people who's going to say, "When we come out of school together, you play the music, and I'm going to make sure that you become popular. I'm going to advertise you." There's got to be cooperation between some of the young entrepreneurs and the young musicians. The world is so crowded now with everything, with people and entertainment and all that. You know, as hip as Dizzy's music was, he was still an entertainer. He danced on the stage. He played the drums. He told jokes. He'd act crazy. You've got to meet the people. They've got their entertainment dollar, they want to be entertained. Nobody can't stand up there like a statue and play.

Now we have American Idol. Millions and millions of people watch that. You know what it is? It's a prize. They say, "Well, oh, maybe, I can do that. If I get on there and I can sing like so and so." And I understand that because a lot of them can and the ones they're "Idolizing" ain't that great. I mean, it's hard to figure out. But I just think that the young people have to figure out something for themselves. We cannot do anything that's gonna make it perfect for them. Who says that every time you come out of school with a degree you're gonna be a millionaire? All of them don't make it in whatever profession. More than ever, musicians are coming out of these institutions.

Take the example of some people I love very dearly, friends of mine, a group called Take 6. They started singing in college together in Alabama or somewhere like that and now they have something like 20 CDs out and Grammys. They are really incredible. There's other groups, like New York Voices -- they met in Ithaca in school. When you're in school, start a group and nurture and build the music so when you finish, you've got a product to sell when you come out. That's what they can do.

Q: Why would young people want to play jazz?

Jimmy Heath: If you get into it, you'll find what's great about it. It's a life's work. If you're a person who is ambitious and curious, you like creative things, jazz allows you a certain amount of creativity that is incomparable to anything. It's like an artist or painter. If you love that and you get into it, that's it for life. Sometimes you're fortunate enough to get rich. But, you know, why do you need to get rich? Okay, you got a house. You got a car. Maybe you got a summer home. But if you got 60 cars, like Reggie Jackson the baseball player had, how can you ride in more than one at a time? One breaks down, you got another one. That's cool. But 60 cars! That's just gross. Why do you need that? You don't need that. You need good health and you need somebody to love and something to love, a profession or art form that you like, and that's it. Life is so beautiful that way.