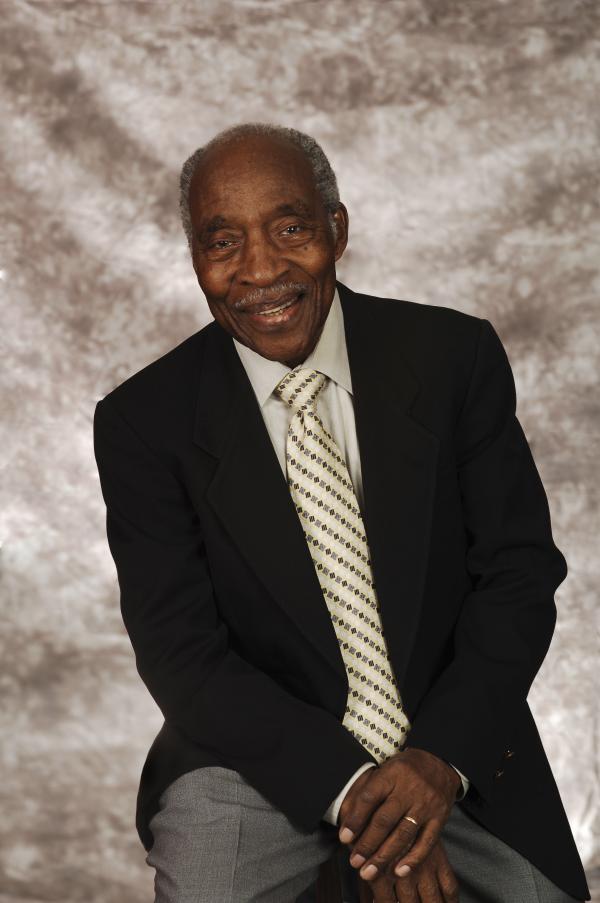

Joe Wilder

Photo by Tom Pich/tompich.com

Bio

"To be chosen as a recipient of such a prestigious award that the behest of one's friends and peers, is extremely gratifying."

Joe Wilder played with a virtual Who's Who of jazz -- Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, Benny Carter, Dizzy Gillespie, Benny Goodman, Lionel Hampton, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Quincy Jones, John Lewis, Charles Mingus, George Russell, and Dinah Washington, to name just a few.

Wilder was born in 1922 into a musical family led by his father Curtis, a bassist and bandleader in Philadelphia. Wilder's first performances took place on the radio program Parisian Tailor's Colored Kiddies of the Air. He and the other young musicians were backed up by such illustrious bands as Duke Ellington's and Louis Armstrong's that were also then playing at the Lincoln Theater. Wilder studied at the Mastbaum School of Music in Philadelphia but turned to jazz when he felt that there was little future for an African- American classical musician. Wilder joined his first touring big band, Les Hite's band, in 1941.

Wilder was one of the first thousand African Americans to serve in the Marines during World War II. He worked first in Special Weapons and eventually became assistant bandmaster at the headquarters' band. Following the war during the 1940s and early '50s, he played in the orchestras of Jimmie Lunceford, Herbie Fields, Sam Donahue, Lucky Millinder, Noble Sissle, Dizzy Gillespie, and Count Basie, while also playing in the pit orchestras for Broadway musicals.

Wilder earned a bachelor's degree in 1953 at the Manhattan School of Music, where he was also principal trumpet with the school's symphony orchestra. At that time, he performed on several occasions with the New York Philharmonic under Andre Kostolanitz and Pierre Boulez.

From 1957 to 1974, Wilder did studio work for ABC-TV while building his reputation as a soloist with his albums for Savoy and Columbia. He was also a regular sideman with such musicians as Gil Evans, Benny Goodman, and Hank Jones, even accompanying Goodman on his tour of Russia. He became a favorite with vocalists and played for Harry Belafonte, Tony Bennett, Eileen Farrell, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Johnny Mathis, and many others.

Selected Discography

Softly with Feeling, Savoy, 1956

Jazz from "Peter Gunn", Columbia, 1959

Benny Carter, A Gentleman and His Music, Concord, 1985

No Greater Love, Evening Star, 1993

Among Friends, Evening Star, 2002

Interview by Molly Murphy for the NEA

January 10, 2008

Edited by Don Ball

FATHER'S INFLUENCE

NEA: Your father was a professional musician -- did he influence you toward music?

Joe Wilder: My father played initially cornet. I never heard him play the cornet because at that time I was an infant. He played cornet for many years, and he was studying with a teacher in Philadelphia who taught piano, trombone, all various instruments. He was a very fine concert cornetist and he told my father to try the sousaphone. And my father tried the sousaphone and he fell in love with it. He gave up the cornet and started playing sousaphone. Some of his colleagues doubled -- they played sousaphone and then they played the bass violin. So he bought a bass violin, took lessons and became a doubler. That's what he ended up doing. He started me playing the cornet.

NEA: Did he choose the cornet for you?

Joe Wilder: He did, yes. I mean, I wasn't even interested in becoming a musician. I was too young to think about it. But if I had had my own choice, I would have probably picked the trombone because my grandparents lived across the street from a catholic school and they had a marching band. And I thought it was just great, these fellows up front with the slide trombones, but my father got a cornet for me.

NEA: Tell me about how you first became interested in jazz.

Joe Wilder: Well, I listened to all these [jazz programs on the radio] because my father did. And as I used to listen, there was a cornet player who used to come on. His name was Del Staigers and he was a fantastic cornet soloist. There were other people too that were on his level and above. But he was the one that I heard because he would be on the air and he had a high-pitched voice and I thought that was funny, but he played so beautifully. I used to say, "Geez, I wish I could play like that." And I was studying from the Arban trumpet book; that's what most of these guys used for their students and what they themselves had been taught from. It had all these cornet solos in there. So after you had learned all of the beginning things you got a chance to play some of these cornet solos, and I could always hear him playing. So that was one who inspired me. I was really interested in playing like that.

PARISIAN TAILOR'S COLORED KIDDIES OF THE AIR

NEA: You performed on a radio program as a kid?

Joe Wilder: In Philadelphia.

NEA: What was the name of it?

Joe Wilder: It was called Parisian Tailor's Colored Kiddies of the Air. They had another children's program in Philadelphia with all white children that was sponsored by Horn and Hardart's Restaurant chain, but there were never any black kids on that program.

This tailoring company called Parisian Tailors used to make band uniforms for all the famous black orchestras, Duke Ellington, Count Basie, Cab Calloway, you name them, all of those orchestras. So they had one fellow whose name was Eddie Lieberman, and he was the chief cutter for the tailoring company and he was dabbling with personal management of entertainers. He had just started. And he said to them, Sam Kessler and his brother Harry, that he thought it would be a good idea if they sponsored a radio program featuring children, but all black kids as a sort of a payback to these orchestras for buying their uniforms from them. They agreed to do it and that's how Parisian Tailor's Colored Kiddies of the Air [came about]. We played on Sunday mornings for one hour.

NEA: These famous bands would come and back you?

Joe Wilder: Every one of them. In Pennsylvania, we had the blue laws and on Sunday you weren't supposed to have any drinking and anything that was jazz or anything that was the devil's way of living. And they had this clause in their contract that said they were off on Sundays so they didn't have any show, but they had to agree to improvise backgrounds for whatever we, the children on the program, did. I played cornet so whenever I played they'd improvise a background to make it look like I was a part of the band. It was very successful, very popular.

NEA: Did you meet any of these musicians when you were playing?

Joe Wilder: Oh they used to come. We met them and they would encourage you. I mean we're even talking about Duke Ellington, who was one of the top bands at that time. They all came and they played for us. The Modern Jazz Quartet had a bass player, Percy Heath, and he was telling me (they lived in South Philadelphia), he used to say how rough it was on him. His name was Percival. He was thin and tall and he played the violin. Only sissies did that kind of a thing you know. And the kids in the neighborhood would just tease him all the time.

NEA: That must be how he built all that strength of character.

Joe Wilder: That's for sure, yeah.

MASTBAUM SCHOOL IN PHILADELPHIA

NEA: You went to the Mastbaum High School in Philadelphia.

Joe Wilder: It was a vocational school. They became famous because of their music department. It was a high school but it was vocational in that they taught many different subjects there. They had carpentry. They had a lot of things and you had to be sort of a specialist to enroll in that school. I had to take an audition at Penn University in order to get into the school, and if you passed that then they accepted you, then you could become a student there. So it was very selective and fortunately it was a big help to most of us.

NEA: You were studying cornet?

Joe Wilder: I was still playing cornet and I played in the symphonic band at the Mastbaum School.

NEA: Was there any kind of jazz instruction?

Joe Wilder: Oh, absolutely not. That was a no-no.

There's a story about Buddy [DeFranco] during that time -- Tommy Dorsey's band was playing all over the country, and they had a young musician's contest that they were running. So if you were one of the contestants and you won, then you were paid by being able to travel with the orchestra I think for a month or two months as one of the soloists with the big band. And he won in Philadelphia, and we were so proud of him because he was one of us. They wanted to throw him out of the school because he was playing jazz. This was just not to be done. It was unbelievable. And we'd be playing music and we'd get to the end of a Beethoven symphony or something like that, Tchaikovsky or something, and at the end somebody would add a flatted fifth, we called it. They would add this at the last chord and the conductor would go crazy. "Who did that?" As if you had just gone out and robbed a supermarket or something. And everybody would be sitting there like, "I have no idea who did it." We'd be cracking up.

NEA: All of your training at that point was classically oriented.

Joe Wilder: Right.

NEA: Were you exposed to jazz? Did you play jazz?

Joe Wilder: I had been exposed to jazz but I wasn't thinking about playing it. All I wanted to do was try to be a good cornet player because I heard a lot of other professional concert players -- I wasn't that impressed with what they were doing. I just wanted to see if I could play as well as they did when I was studying.

NEA: Did you have dreams of being in an orchestra?

Joe Wilder: I thought maybe I would, but I was so young at that time that I was happy to be able to get through with whatever I had to play. And I hadn't zeroed in on any particular phase of music. My father being a musician, he listened to everything, classical, the Baja bands from Mexico. At that time we had the Atwater Kent Radio and you could turn the dial and you could get stations all over and into Mexico. So we heard a variety of different types of music and I was kind of inspired by that.

I had never even given a thought to the fact of playing maybe with a mixed orchestra because there just weren't any at that time. There were no mixed orchestras. And I've often seen some quotes where they said I decided I would go into jazz because there were no opportunities. I wasn't aware of whether there were opportunities or not. I hadn't reached the point where I was professional enough to do any of those things.

I was really led into it with the people with whom my father worked. My father became a bandleader after World War II. He was in the service at that time. I was in the Marine Corp. My father was in the Navy and my two younger brothers were in the Army. But when he came out, he was so disgusted with some of the things that he had had to put up with as a sideman before he went into the service, he decided to organize his own group. And he had a group; he called them the Six Bits of Rhythm and they played society dances. Most of the jobs they played were for white audiences. And so that's how that got started. They always say, "Well, his father was a bandleader," but he wasn't when I was younger.

PLAYING IN THE MARINES

NEA: The armed forces provided a great experience for a lot of musicians playing in bands during that time -- was it difficult to get yourself into a band?

Joe Wilder: It was in a way and I was there again fortunate because I had someone who was actually helping me and was responsible for getting me into the band at Montford Point. That's where all the African-American Marines trained. We had all white officers and non-commissioned officers, but all the black Marines trained at Montford Point Camp, which was one of the camps in the overall camp of Camp LeJeune, North Carolina. The headquarters camp is there. And so I was pretty good at shooting a rifle and I made sharpshooter, and usually if you did that they would take you out and put you in special weapons units and you trained with them to be snipers and things like that. But I was only in that for a short time because Bobby Troup, who wrote "Route 66," he was one of the officers down there and he knew who I was and he decided that it's silly to have [me] in this outfit. And he went to the general and said, "We've got a guy here who's been playing with Lionel Hampton's orchestra and why don't we put him in the headquarters' band and it would boost the morale of the troops." He had to persuade him to let me do it. So he transferred me from special weapons into the headquarters' band and after the first year I was promoted so I became the assistant bandmaster.

NEA: Did you play just for the enjoyment of people at night?

Joe Wilder: On weekends we had a dance band within the military band, and we used to play at the Officer's Club and then we used to sometimes go to the USO and play for the servicemen who were there lounging around. That was a place they could go and hang out or meet their girlfriends or their wives or something like that. So we did that kind of a thing to boost the morale too.

NEA: Did you run into any other musicians who then went on to be famous?

Joe Wilder: Where I was stationed I didn't because the Marine Corp had just begun accepting African Americans. So there were very few people who had played with name bands. When I went down I was classified 1A like everybody else. And they asked me what I did. I said I'm a musician. And I was told, "We're not accepting any more non-combatants." This Marine sergeant said, "Maybe you'd be interested in going into the Marine Corp? The Marines are just now beginning to accept African Americans and maybe you'd like to go in that." I said, "Well if you tell me I can't get into a unit as a non-combatant, if I'm going to have to fight it might make sense for me to go into the Marine Corp and learn how." So he said, "That's a pretty good idea. Would you like to join?" I said yeah and that was it and so I ended up there.

NEA: What big band experience did you have before you did that?

Joe Wilder: Well I had played with Les Hite's band. I had been playing with bands in Philadelphia. When I went into the Marine Corp I was with Lionel Hampton.

ON THE ROAD

NEA: What was the experience like in the '40s and '50s touring with big bands? You were on the road for a long time -- was it difficult to try to have a family?

Joe Wilder: Yes, because you're away all the time. The really famous black bands (and the white orchestras too), their families just went down the drain because they were never home. I mean, sometimes six months at a time. And they'd come home and be home for awhile and then they're gone again, so it was difficult in that way. But the camaraderie that developed between the players in the band was very strong because we had to depend on each other many times for survival. We'd run into some very bad situations, one of which I remember.

We were in, I think, Georgia or Alabama. It was with Lionel Hampton's band. And we were getting ready to leave town to go to someplace else by train. So we're all getting on the train and in those days all the blacks had to sit in the car that was closest to the locomotive that was following the train. And they had these coal burning cars and the soot would be coming in through the cracks in the thing. You'd be coughing, it was so bad sometimes, but that was the only car they would let you sit in. And Illinois Jacquet was a little late getting there. The train hadn't left yet, but he got there a little late. And in order for him to get on the train he had to jump into the car, the first passenger car that was closest to where he was coming into the station. And he jumped on this car and it was in the section where all the white passengers were, but he's going to go up to the front. And on his way up he runs into the conductor. And the conductor had a white beard and sort of a Kentucky Fried Chicken look about him. And he looked at him and he said, "Boy what are you doing down here?" And Jacquet said, "I'm trying to get up to the car up there, and who are you calling boy?" [The conductor] said, "Hey where do you think you are? Boy, I'll shoot you," and he pulled out one of these pistols about this long and threatened him with it. So [Jacquet] came up, kept on till he got to the black car. He gets in the car, took a seat, and this guy followed him all the way up and he's chewing him out because he answered him like he did. And at one point he said something and he pushed Jacquet and Jacquet was going to swing at him, and he pulls out his pistol again and said, "Boy, I'll blow your head off if you do."

And at this point, we were lucky because our manager had red freckles, red hair, and he was from Texas. And he had his Texas drawl, so when this guy looked at him, he said, "What's going on here?" And the guy said, "Them young niggers over there. You better teach them how to behave while they're down here 'cause they're going to get you in a lot of trouble. [Our manager] said, "That's okay. That's all right. I'll take care of that." And so the guy backed off and left us alone. But that was the closest we came to having a real scene because some of the guys in the band carried pistols. And the conductor when he got off, he went off and came back with a lot of guys who purported to be members of the Klan. They didn't have robes on, but they were there and if he needed them he said, he'd call them and they'd come. Now the band on the train, the guys who had pistols are saying, "I've got mine if they come in here." This is how close it came to being one of those things. It would have been a disaster, you know, but anyway it didn't happen.

But at the same time, on the other hand, you have to be decent enough to mention that there was another side to it. There were always a lot of white people who were opposed to what was going on too. And every time they had an opportunity, they would try to do whatever they could to help get rid of it, but it was difficult. I played with Sam Donahue's band after Jimmie Lunceford died and these guys were very fine players and really nice guys. Doc Severinsen had left the band and I went in his place. And the guys in the band were very nice to me. But we would go to places, Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, and places like that, and we walked in and they'd say "Okay, you're welcome." Then they'd see me and say, "Hey what about him? We don't serve those people in here. Are you kidding?" So we'd just pack up and leave. I mean that's the way it was. But they were hurt because now I'm a friend of theirs and now they're seeing how this thing works up close and they had never been a part of it. So it was really devastating to them too, but it happened, you know.

JAZZ AND CLASSICAL

NEA: Do you think that your training in classical music affected the way you approached jazz?

Joe Wilder: It made me probably a little more disciplined. In classical music, you're obligated to play just what's there using the dynamics and the harmonic structures of whatever it is. You do it under the direction of the conductor. So as long as you are doing it to his satisfaction, it's okay, but you don't take liberties. And in jazz you have more freedom. I mean you may see something that may not be a solo but may be just an ensemble thing. And if you're the first trumpet player or saxophone player, you can tailor it the way you think it sounds best in a way that reflects your style of playing, and it helps to make the style of the band too. In classical music it requires, in many instances, a lot more discipline, because although you're playing something, and you may play it every night or at every concert, you still got to make up your mind that you're going to play it as well as you can this time as you did the last time. You learn all the idiosyncrasies of the conductors.

I think to some extent the reason that some of the friction that developed between classical players and jazz players developed was because it seemed like it was a status thing, that if you improvised there was something wrong with you, that this was something you shouldn't do because of the rigidity of the classical playing where you just play what's there. It's like the train on the track. The train goes on the track no matter where he goes. And it was the same kind of a thing with playing the classical music -- you didn't deviate and play this music a certain way except at the behest of the conductor.

I was playing at the Music Hall, subbing at the Music Hall, and one of the trumpet players said "Well, you know I never liked to play on the instruments that the jazz players have played on because they play and the instruments are out of tune and it does something to the metal." It's so ludicrous. It doesn't make sense, you know. But that was another thing that meant that I'm better than you as a player because I play classical music.

But I'll tell you, you need a lot of self control and things like that if you're playing classical music. I did a show, Most Happy Fella , a Broadway production -- it was like an operetta. And Anton Coppola was the conductor. He's the uncle of the film director and he had been with the Metropolitan Opera -- top-notch musician, and he was an excellent conductor. He would say to me (I was playing principal trumpet), "Tonight Joe, like all the other nights, we're going to play an opening night performance," which meant we were going to play as if this was the first time we're doing it. And it was a challenge because I'd go in there and he'd say this. But it was a lot of fun actually just to see that you could do it because in a Broadway theater and you're doing a show, you're playing the same music every night or every matinee day at the same time. So it gets very boring unless you can discipline yourself to try to do it as well as you can each time you know. It's challenging.

RECORDING

NEA: Tell me about some of the records you made.

Joe Wilder: Well, I did a couple of recordings for Columbia Records and they were kind of unusual because I was able to select almost all of the things that I played. The one I like best of the albums that I've done is Pretty Sound because it was a variety of things that ordinarily so-called jazz trumpet players wouldn't have been allowed to record. It's just because it's more lyrical and things like that. But it's a variety of things and it gave me a chance to play different styles you know and interpret some of the things that I played. But that was the first time that I did an album on my own. And we did another one with music from the Peter Gunn television show and some others. And then I've done three with Evening Star, which was Benny Carter and Ed Berger's company.

NEA: What about the recordings you made with Savoy in the 1950s?

Joe Wilder: What we used to do, they used to call us and say, "Can you do a date on Monday?" or whatever the date was. And you'd say okay. And we went in and they'd say, "What would you like to play?" We had no arrangements and we would just make these things up as we went along. We had played together on different occasions but not necessarily recording dates. Somebody would pick something [to play] and I would pick something. And that way we'd get the number of pieces we were going to play and then we'd start playing, run through them and start improvising and see what could we come up with. We'd call them head arrangements, right off the top of your head, and we'd do that. Then we'd have them. Now when we finished, we'd recorded eight or ten pieces, we'd get through and the manager or the company owner would come up and say, "We're making you the leader on this one. You're the leader." I don't remember what they paid. They didn't pay a great deal of money. But let's say if they paid $100 for the session (it would go more than three hours or so), they'd say, "Well you're the leader, so we'll pay you $150." You get $150. And we never got another penny from any of that stuff, no matter how many of them they sold.

I have to tell you, there's one album [I recorded] that has a comic thing to it. When I was a kid, Benny Carter was one of the most talented musicians anywhere in the world. And my father admired him and he used to say to me when I was a little boy, "Listen to that Benny Carter. That rascal, listen to him playing the trumpet. He plays the piano. He plays the saxophone. Listen to him." My father never got to meet Benny personally, but he admired him. And one day, before my father passed away, he and I were talking and I said something to him. He asked me, "What have you been doing lately? Did you do any new recordings?" I said, "Well no, but recently I did a recording with Benny Carter and we did it out in California." So my father said, "Oh yeah." And we kept talking and he said, "Wait a minute. Wait a minute. Did you say you know Benny Carter?" I said, "Yeah dad, I did an album with him." "You did an album with Benny Carter? I can't believe it." I said, "Benny Carter's a friend of mine, Dad." "Benny Carter is a friend of yours?" And now we keep talking and every once in a while he says, "I can't believe you know Benny Carter." And you see my stock going up on the graph and it just broke me up.

I told Benny that story. Now Benny had forgotten how much older he was than me. And here I am in my 70s telling him that my father was so proud of the fact. He said, "Oh come on, Joe."

NEA: Your father must have been so proud of you.

Joe Wilder: And my mother of course, my mother was, that was it. She loved my brothers too. My older brother was a bass player, so we were the musicians in the family.