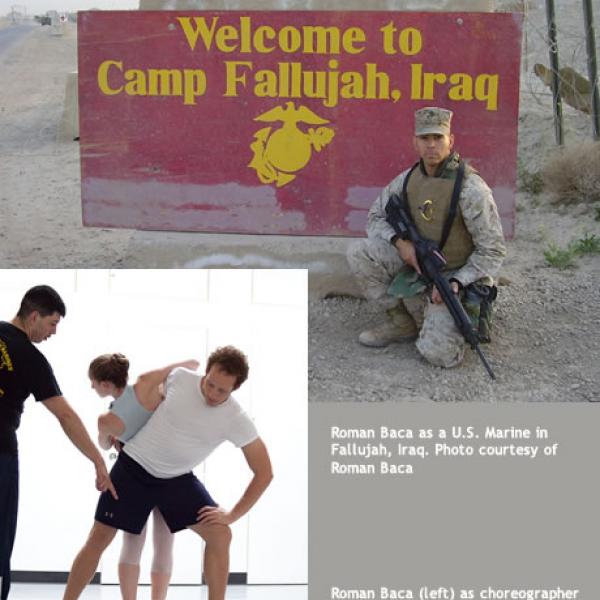

Art of the American Soldier

A woman in uniform studies the exhibit at the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, Pennslyvania. Image provided by the National Constitution Center.

When a war poses for its picture, it leaves to the artist the selection of the attitude in which the artist may desire to draw it. And this attitude is the artist’s point of view circumscribed by the boundaries of his ability and the nature of the work for which his training and practice have fitted him. -1919, World War I soldier-artist J. Andre Smith

:: From September 2010 to March 2011, the National Constitution Center in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, housed the Art of the American Soldier exhibit. The 6,000-plus-square-feet exhibition featured more than 200 artworks in various media, ranging from elaborate paintings to casual sketches—all created by soldiers. “The National Constitution Center is proud to make this remarkable visual record available to the public for the first time,” said National Constitution Center President and CEO David Eisner, who called the exhibit “breathtaking” and “astonishing.” The paintings were supplemented by recordings of oral histories from soldiers, adding intricacies to the already vivid stories within the works of art. Divided into five separate sections—Introduction, A Soldier’s Life, A Soldier’s Duty, A Soldier’s Sacrifice, and The American Soldier—the exhibit gave the sense of a real war story, with a beginning, middle, and a hopeful ending. Visitors were able to actively respond to the works on view by writing a postcard or two at the letter writing station positioned near the end of the exhibit. These postcards are then mailed to soldiers thanks to the Letters for Lyrics program, a partnership among Ram Trucks, the Zac Brown Band, and Soldiers’ Angels, which encourages the public to send letters to troops in return for a compilation CD.

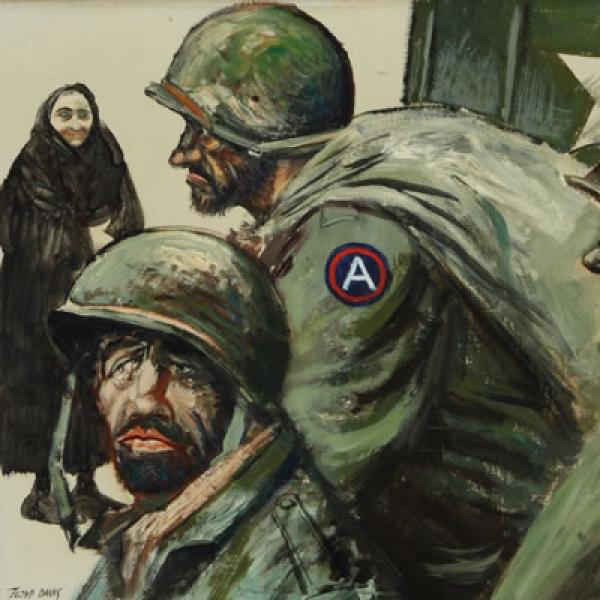

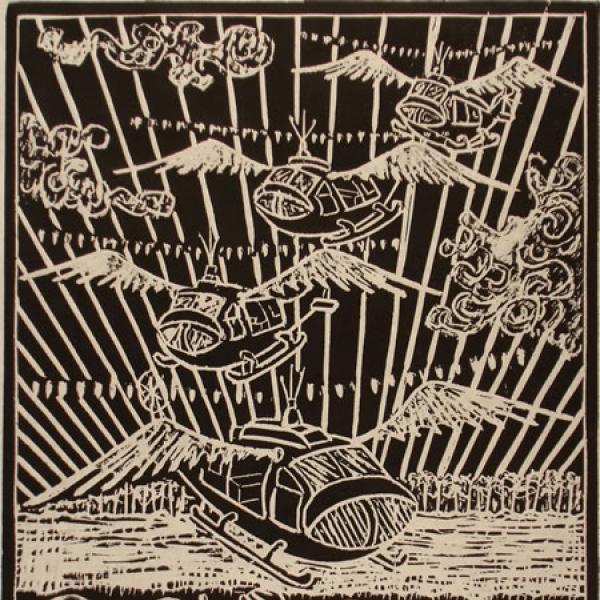

All of the artwork on display at the National Constitution Center came from the U.S. Army’s art program, which has produced more than 15,000 pieces of art since its inception during World War I. The program was started when the United States Army sent eight artists, commissioned as captains in the Corps of Engineers, to Europe. Their duty? To record activities of the American Expeditionary Forces. During World War II, the Corps of Engineers took the idea a step further and created a War Art Unit. With the unit came the development of the War Art Advisory Committee, a group of arts experts who were to nominate military and civilian artists to serve in the unit. During this time, the art produced was given to the Smithsonian Institute, the then-custodian of Army historical property.

The art program was abruptly cut from the Army’s budget in 1943 due to claims that it was a frivolous program, leaving many artists shocked and saddened. However, Life magazine and Abbott Laboratories stepped in to keep the art alive.

Life Executive Director Daniel Longwell made an offer to the assistant secretary of war, John J. McCloy, proposing to hire all of the civilian artists as war correspondents. Seventeen of the 19 original artists accepted the positions. Though these men were not enlisted in the army, they were intimately engaged in the war—flying in bombing raids, going to Omaha Beach directly after D-Day, and dodging enemy fire. These men were on the battlefield.

Abbott Laboratories was known for supplying drugs and other pharmaceutical supplies overseas, but they also were very involved with supporting American artists, and believed that artwork could boost American support for World War II. They made an agreement with Associated American Artists and the War Department that ensured the artists a daily wage and a place to sleep, thereby creating jobs for more than two dozen artists, eager to capture the true sense of war. These artists went into the battlefield as well, serving officially as “combat artists.” After World War II, the art was donated to the War Department (now the Department of Defense).

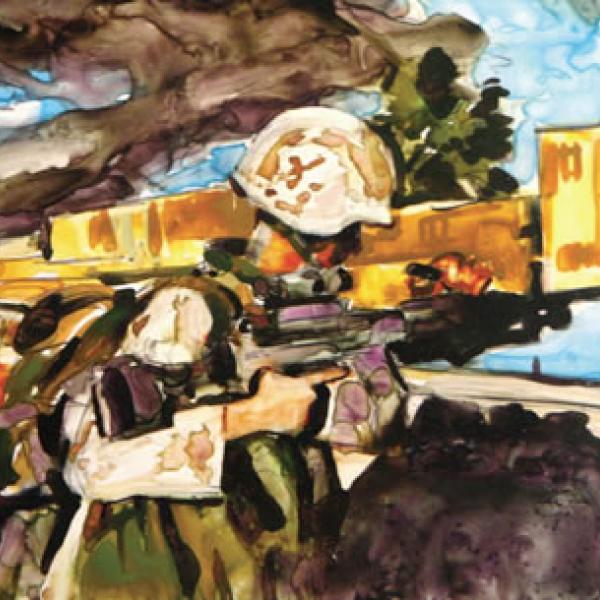

The United States Army art program was reinstated in 1944, just one year after it was cut. Today, the thousands of creations, made by over 1,300 soldiers, are in the care of the Army’s Historical Properties Section, established by the Army in 1945. And the art keeps coming in—the most recent focusing on the War on Terrorism, featuring works from soldiers in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Kuwait.