Strike Up the Band!

The U.S. Army Blues Jazz Ensemble at Blues Alley in Washington, DC. Photo courtesy of the U.S. Army Band "Pershing's Own"

"Where Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios' motto is ars gratia artis, ours could be ars gratia America," said Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Price, who serves as chief of music for the United States Air Force. "Instead of making art for art's sake, we make art for the sake of our country."

In a nutshell, such is the vital, yet often underestimated, mission of Price, his musical Air Force colleagues, and thousands of other full-time military musicians who populate bands across the armed forces. Whether representing the Air Force, Marine Corps, Army, Navy, or Coast Guard, military musicians' duties go deeper than simply playing the right notes to the "The Star-Spangled Banner" come Fourth of July. As Price described it, band members of the armed forces "render official honor for the United States with each performance and represent so much more than just themselves." And as Price and countless other military musicians have discovered gig after gig, such acts of musical patriotism can have profound effects on local, national, and even global levels.

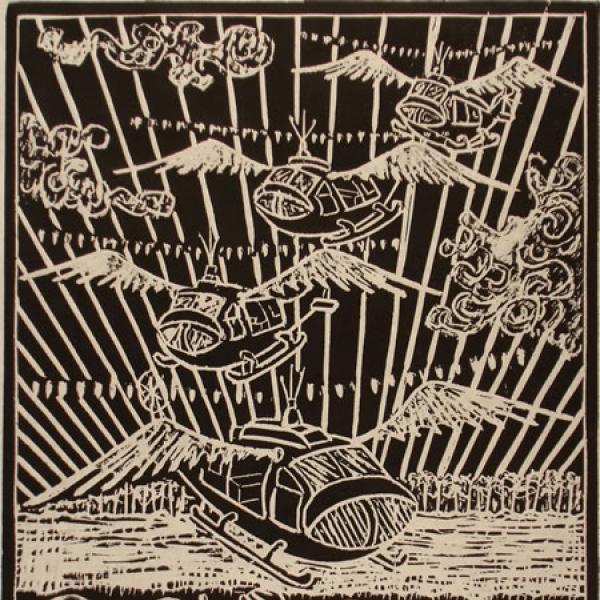

The bond between music and the military is neither new nor unique to the United States. "From the Janissary bands of the Ottoman military in the 14th century to the iconic images from our own Revolutionary War of drum-and-fife players coming back from the front, the relationship between music and the military has been an important one," Price noted. "Those Revolutionary War musicians had been bloodied in battle, but they were still there leading the parade and representing the spirit of the people."

|

Though drum-and-fife players no longer accompany Minutemen into battle amidst blazing muskets and bellowing cannons, military musicians apply their talents in a wide variety of contexts. "I consider myself lucky to have had an opportunity to take part in some incredibly important national events, like welcoming ceremonies for kings and queens, the funerals of Presidents Reagan and Ford, and playing fanfares for presidential inauguration ceremonies," said Staff Sergeant Chris Branagan, a Texas native who joined the U.S. Army Band as a trombonist.

Branagan has honored fallen soldiers at Arlington National Cemetery as well, a task he said is never easy but is the most meaningful work he does as a military musician. "It's about the United States rendering honor and giving thanks," said Price, describing his own work honoring fallen airmen at military funerals. "Playing ‘Taps' for someone who has given his or her life, capturing the feeling of mourners and saying an official goodbye in honor of service -- it can be difficult, but it's a powerful mission."

Military musicians are regularly called upon to perform at the highest of levels with tremendous poise and dignity, regardless of location, playing conditions, or repertoire -- a demanding set of requirements, to say the least. "Auditioning for a premier military band is almost identical to auditioning for a major, full-time symphony orchestra," said Branagan. "The process is intense and the pressure is high."

|

Colonel Thomas H. Palmatier, a conductor and multi-instrumentalist who serves as leader and commander of the United States Army Band "Pershing's Own," thrives amidst the demands of the job. "Every day's schedule was different and I was encouraged to use all of my talents as a versatile performer, to arrange music, and to lead small groups and combos," he said of his early years as a military musician. "There's not a day that goes by that I'm not excited about some aspect of my job."

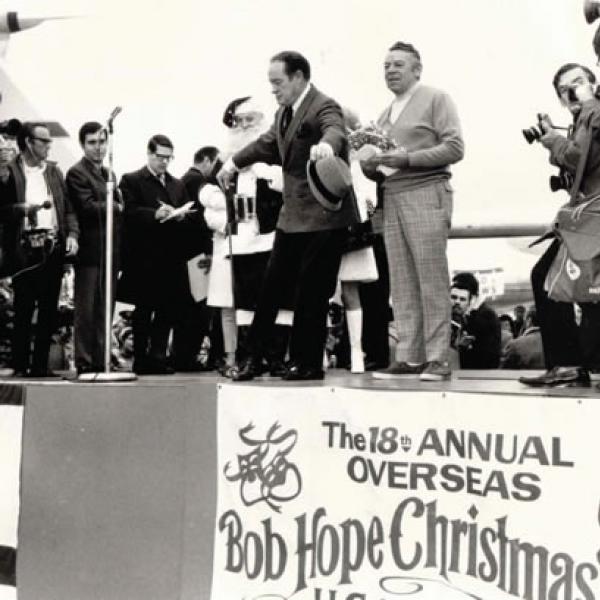

Jazz and the MilitaryMilitary bands have played a predominant role in the early careers of many jazz artists, a place where they honed their skills as musicians. Of the 128 NEA Jazz Masters, approximately one-fourth spent time in Army, Navy, Marines, and Air Force military bands. NEA Jazz Master Joe Wilder was in the Marine Corps during World War II, and talked to the NEA about his experience: "I was pretty good at shooting a rifle and I made sharpshooter, and usually if you did that they would take you out and put you in special weapons units and you trained with them to be snipers. But I was only in that for a short time because Bobby Troup, who wrote ‘Route 66,' he was one of the officers down there and he knew who I was… and he went to the general and said, ‘We've got a guy here who's been playing with Lionel Hampton's orchestra. Why don't we put him in the headquarters' band? It would boost the morale of the troops.' He had to persuade him to let me do it. So he transferred me from special weapons into the headquarters' band and after the first year I was promoted so I became the assistant bandmaster. "On weekends we had a dance band within the military band, and we used to play at the Officer's Club and then we used to sometimes go to the USO and play for the servicemen who were there lounging around. That was a place they could go and hang out or meet their girlfriends or their wives or something like that. So we did that kind of a thing to boost the morale too." |

Due to limited rehearsal time, the high-profile nature of most performances, and the stylistic diversity required of military musicians (repertoire can often range from patriotic classics to Adele and beyond), Branagan finds that preparation, and a wealth of prior experience, are keys to success. To gain the chops necessary to thrive in such challenging settings, military musicians often work for years as civilian musicians before ever entering the audition room. Branagan is a former music professor with significant freelance performance experience. Price holds a DMA in conducting. Palmatier earned an MFA in music and performed pop, jazz, and classical on a variety of instruments before joining the military.

In addition to their duties at home, military bands play key roles in ceremonies around the world, often serving as morale-boosters, ambassadors, and diplomats, all at the same time. Palmatier recalled a momentous performance in Russia to commemorate the 60th anniversary of V-E Day. "Marching through Moscow behind the Stars and Stripes with over one million Muscovites on the streets was quite a thrill," he said.

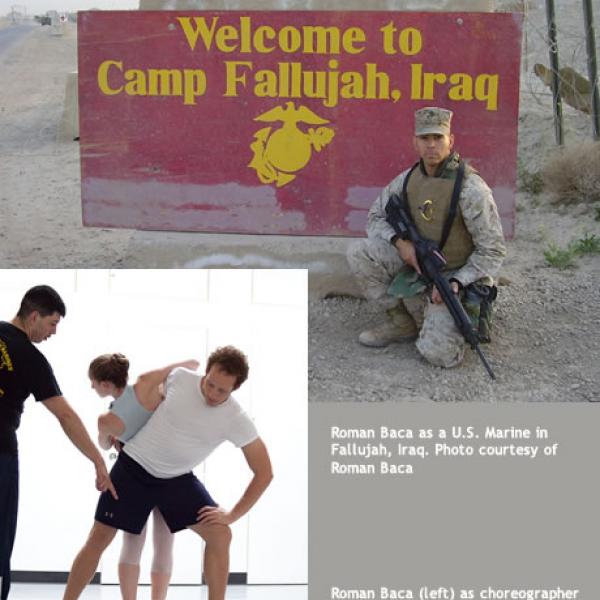

Both Palmatier and Price have found great meaning in their work playing for military members in Iraq. "On one occasion, our band performed for some Marines that had been deployed for over a year," said Price. "They were a long way from home and the ability to go out there in uniform, play for them, show them that we care and value them, and provide them with a bit of relief and a reminder of home can be an incredibly powerful mission."

Price also recalled times when the work of Air Force musicians has helped build bridges internationally. "One of our bands was stationed in Tokyo and invited to tour Thailand in 2005," he said. "The goal was to perform in cities that had hosted U.S. bases during the Vietnam War, to say thank you, and to entertain and build friendships with younger audiences who may still have been making up their minds about the U.S."

The tour began with a performance for the king of Thailand, a beloved monarch who had studied in the United States and become a fan, and amateur composer, of American jazz. "We not only played for the king, which was a tremendous honor, but we created big band arrangements of a few of his compositions and played them for him in his own palace," said Price. Attending the performance were a number of American officials, including the consul general in Bangkok. "Because of this event, the consul general was invited, along with his staff, to meet the king for the first time," said Price. "That connection and added prestige really helped him in his role representing the United States and working within Thailand."

|

A similar tale unfolded in 2011 at the Transit Center at Manas (TCM) in Kyrgyzstan. "The TCM is a critical airport to U.S. operations in the current war effort and we dearly appreciate the relationship that we have with the Kyrgyz that allows us to use it," said Price. "We've had to work hard to maintain such a positive relationship, and to build relationships with the Russian military, which has a local airbase in the country."

While previous efforts to reach out to Russian military counterparts had yielded lackluster results, an Air Force Band performance at Manas succeeded in capturing their attention. "The Russians were invited and, for the first time, they were interested," he said. "They were blown away by the performance and everyone had a wonderful time. We were able to meet the Russian soldiers and, as a demonstration of goodwill, their leaders even extended a reciprocal invitation for U.S. airmen to come to their airbase. In this instance, it was the musical performance that brought those two militaries together."

Working in their artistic field and serving their country is something that makes being in a military band so momentous. Often in pre-concert discussions, Palmatier is asked which performance was his favorite. "I really want to say, ‘this one,'" he stated. "Performing music in the service of America never gets old."