The Sacrifices That Have Been Given

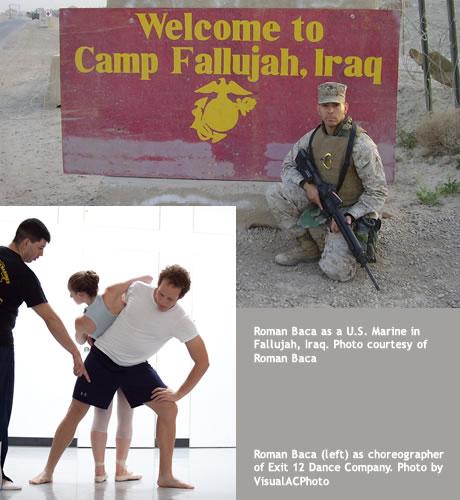

Dancer, choreographer, U.S. Marine. To some, those labels together would be jarring, but for Roman Baca, his life as a dancer and his experiences in the U.S. Marine Corps are essentially intertwined. As artistic director of Exit 12 Dance Company, he uses the beauty and language of dance to communicate his own experiences as a service member in Fallujah as well as those of other members of the military and their loved ones at home.

In his own words from an interview the NEA conducted in June 2012, Baca explains his journey from the stage to the battlefield and back again.

* * *

Drawn to Dancing

When I was in high school I had a really good friend who was a ballerina and she used to tell me about all the things she would do at dance school -- the interactions between her and her partner, the challenge of it, and I got interested and saw two of her performances. One of them was at a local mall where she did a solo to "Wind Beneath My Wings" in the middle of the mall with a tape recorder playing the music and I was enthralled. I moved to live with my father in New Mexico and I had the opportunity to go and start lessons at a small dance school in a strip mall. And because there aren't that many men in ballet, I got scholarships just to show up. And that's how I started my dance training.

Becoming a Marine

After being a freelance dancer for a couple of years, I realized that the career of being a dancer would be incredibly hard. On top of that, I was struggling to prove to a lot of people and to myself that I could make a living, that I could accomplish things outside of the art world. There were things that I wanted to challenge myself with and I knew the Marine Corps could challenge me. I also wanted to serve my country. I wanted to embody what the Marine Corps stood for and the good things that come from being a Marine.

I didn't tell anybody [I was a dancer when I enlisted]. In boot camp, I didn't want it to change how people felt about me so I kept it under wraps. I was dating a ballerina at the time I was in boot camp, and she sent photos of us inSleeping Beauty. Some of the guys were looking over my shoulder. Two of the guys thought it was really interesting and asked me more about it. One of them never talked to me again.

Even in Fallujah, it took me quite a while to tell my unit because I was afraid of how they would treat me. I was afraid they would look at that before they would look at my real performance [as a Marine]. In Fallujah we spent so much time together that you run out of things to talk about when you're in a bunker with another guy or you're on patrol for hours. I started telling people I was in performances and I did performances on stage, and then that turned into I did dance productions [then] that turned into, I was a ballet dancer. Not only was my unit not fazed by that, one of my friends, my roommate in Fallujah, helped me design the first piece we ended up creating when we got back and he performed in a couple of the performances that we did of Habibi Hhaloua.

|

Starting Exit 12 Dance Company

When I got back from Fallujah, I thought everything was fine. I had tried to transition into civilian life and did all the things that I thought people did when they got back from war -- I tried to go on vacations, I tried to get closer with my girlfriend, I tried to buy a condo and get a real job, a desk job where you work on a computer and sign papers. I thought things were fine. My girlfriend at the time, she sat me down and said, "You know, you're not okay, things are different, you're not the person you were before you left for the war." She said she'd noticed some depression, an increase in anxiety and anger, and that she wanted to help me work through those issues. She said, "If you could do anything you wanted to do, not thinking about money or time, what would you do?" I said, "You know, I've always wanted to start a dance company." And so she said, "Let's do it."

We got two dancers and I started choreographing in New York City -- just movement to music and working out steps and trying to be creative. Nothing really came of it until I decided to start talking about things that were important to me and exploring the military aspect of my life and the way that the military and the wars have affected people connected to them -- whether it's directly connected as a military member or inadvertently connected as a loved one or a mother or a wife or a lover. Once I started talking about those things, [Exit 12 Dance Company] took on a life of its own and it really underscored the need for this. We started talking about the military experience as a way to inspire others to be cognizant of the sacrifices made by the people involved, to advocate for veterans and their families, and to be educated about the experiences and challenges that they face. After four to five years of doing this work, it has allowed me to express things that I was going through and that I felt other military members were going through coming home.

A lot of things I couldn't put into words or I couldn't wrap my head around. With movement, we could really explore it without saying anything. So it was not only helpful for me, but taking the work around and showing veterans opened them up to conversations and saying, "I can tell you've been there, I recognize this, I recognize that, it really spoke to me." It also opened up family members and loved ones to recount stories that they remembered.

The Creation of Homecoming, a Ballet in Three Movements

Habibi Hhaloua was a very personal piece. It was about my platoon, the people I served with in Iraq. But to keep the work honest, I wanted to start talking about more people and the people who were affected by the war. Not only the military people that were affected, but their families and the perceived enemy -- the villagers that weren't a part of the operation, that weren't insurgents.

I spent weeks looking for music to set that work to. And there was nothing I could find that could evoke the sort of feelings that I felt were necessary to communicate. I got the idea of using letters. The School of Visual Arts here in New York City donated some space to record the letters. A couple of actors donated their time so we spent an afternoon basically reading tons of letters. And then I took all of that material home and cut it up on a computer with some editing software and put some music behind it to soften the harsh parts, to make people really listen. At certain times in the ballet the letters get extremely, extremely personal so I coupled that with a crescendo in the music so that if the audience member wanted to hear, they really, really had to listen.

The beginning of Homecoming talks about three women at home who are trying to occupy their time doing mundane things that keep them off of what they're missing -- their soldier overseas. And we tried to put all of the things the letters didn't say into the movement. The longing, the pain, the fear of not knowing what that military member is going through. I tried to communicate that inHomecoming, that feeling that here at home, these people are scared and afraid and they are torn apart by missing that person overseas but in contrast to that, they try to give as much support and encouragement when they talk to them so that they can do their jobs.

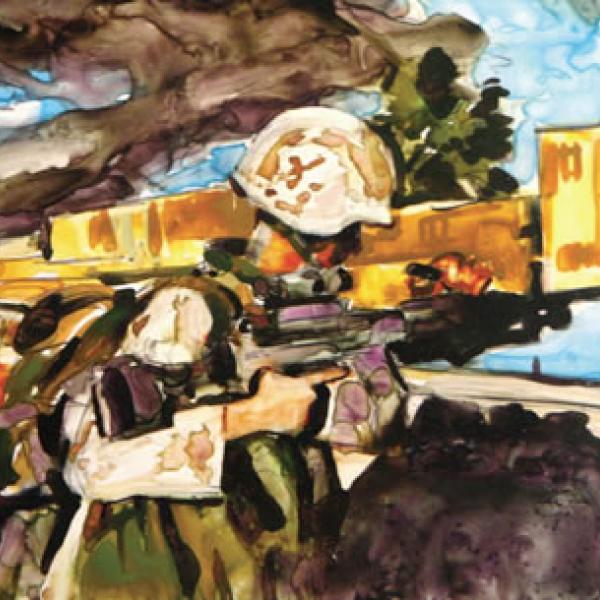

Then we talked about this altercation that happened when I was in Iraq with an Iraqi family. We were at a checkpoint when we detained an Iraqi civilian and we called our quick reaction force to come out and to detain him so that he could go through processing. When the quick reaction force came out, they tackled the guy, and threw him to the ground and used force that was questionable. I never really came to terms with the right or wrong of it so I put it on stage to explore it more. When we performed it the first time, I played the Iraqi male and it was a completely eye-opening experience, being on stage and trying to make that experience of Iraq come to life and feel the feelings that the Iraqi family felt.

The last movement of Homecoming we call the airport scene. Two Marines come home and they're reunited with their loved ones. You have the two different couples: that couple that even though he was overseas, the minute they see each other it's like they were never apart and they're like two magnets that snap back together. And then you have the other couple who are like those magnets that you turn over and they have that little bit of repelling -- the distance created has pushed them apart in some way. The homecoming is a little bit abrasive for them and uncertain but all it takes is a little bit of give from one of the magnets for one of them to flip over and snap back together. Then we tell the story of one of the women who shows up at the airport, and her husband was injured a couple of days before and nobody told her. She's the last one left on stage in order to plead with the audience to open their eyes to the sacrifices that have been given by so many people, and the sacrifices that continue to happen with all of these people still in Afghanistan, working day in and day out to make the world a better place.

|

A Fellowship with Battery Dance Company

After five years, I thought we were doing a good job, we were progressing, we were eventually going to get to the place I wanted [Exit 12 Dance Company] to go. And then there was a Marine by the name of Clay Hunt, who I got word had committed suicide. Clay Hunt served two tours in Iraq and one tour in Afghanistan. And when he came back he was the epitome of not only the Marine's Marine, but of the veteran's veteran. I had known about Clay and I had followed him as a kind of role model, as to how to transition back. And his suicide really rocked my world. I decided that I wasn't doing enough for veterans or for that community and I decided to do more.

I volunteered with Mission Continues at a service project that they were holding; it was one-day service project building care packages for children in hospitals. I met one of the recruiters, who was also a Marine. I agreed to apply for a fellowship [with them] and I started making appointments in New York City to find a host organization. Mission Continues pairs a veteran with a host organization that the veteran can volunteer for during their fellowship and accomplish missions that are set out by the host organization. I interviewed with quite a few organizations here in New York City that had ties to the arts. The minute Jonathan [Hollander, artistic and executive director of Battery Dance Company] and I sat down and started talking about the fellowship, we both knew that our collaboration was the one that would make sense, because we could use his dance program, Dancing to Connect, and augment the program to be used by veteran populations and also to possibly go back to Iraq and use the program in Iraq with Iraqis.

When we got word of the fellowship, I started immediately working with Battery Dance, getting trained in their Dancing to Connect program not only as a teaching artist but as a program facilitator. We had workshops at Battery to learn how to conduct the Dancing to Connect program, how to work with the students, and how to derive movement from improvisational exercises and choreographic exercises to get the participants to inadvertently create their own work. [We also learned] how to engage [students] in a higher level of thought, of discussion, of pulling thematic elements out of things that had happened to them or things that were happening in the world or other written or visual elements that we could apply to the current situation in order to create this cohesive dance piece of movement that spoke to something that was important to them. On top of that, [Battery Dance] also gave classes on working overseas, the visa process, what to do building up to the program, working with the U.S. State Department as well as troubleshooting when you get on the ground.

I did a mock program in a New York City public school so that I could gain experience working with the [Dancing to Connect] model. Then we started building up for Iraq. I started researching what the culture was going to be like, what the students may or may not have experienced, what kind of experience they would have with local dance as well as if they had any experience with the other dance styles that are used around the world.

I had meetings with Iraqi-American artists in New York City. I met with a young man by the name of Fadi Khoury who is an Iraqi dancer. We had a meeting to talk about the cultural differences, what to expect on the ground, how to interact with the young people and basically tips to facilitate the program. I also talked with a former translator, Max, that we had in Iraq and he gave me some tips as well. He said that he was very excited and proud that I was going to his country now with art and that his countrymen would accept me with open arms because of the program I was bringing.

|

Traversing Ethnic and Religious Divides through Dance

Jonathan [Hollander] was working with the U.S. State Department in Kirkuk to get a [Dancing to Connect] program running but it was decided that Kirkuk was too dangerous to do the program there. So they contacted the Performing Arts Institute and the consulate in Erbil. The Erbil consulate agreed to have the program with the stipulation that half the students had to be from Kirkuk. We ended up starting a program in Erbil for 30 students -- half of them were from Kirkuk, half of them were from Erbil. We didn't realize it was going to be a challenge [to have students from different cultures]. I did some research into the culture and the three religious divisions that I knew existed -- the Sunni, the Shia, and the Kurds, as well as the Christian. When we got there, our interpreter clued us into the fact that there were many more in the north. The Kurdish came from Erbil and the Arabs came from Kirkuk.

It was a five-day program so we worked six hours a day with the students who were ages 17-22. On the first day the students from Erbil and the students from Kirkuk sat on different sides of the courtyard during lunch and during the very beginning of the program, they would make snide comments, referring to the group from one city and the group from the other city.

Part of the program is mixing the kids up. So every chance we got, we tried to pair someone from Erbil with someone from Kirkuk. We tried also to pair male with female. Both Fadi and Max warned us that probably we would have to separate the females and the males. When we got there, it wasn't the case, they actually worked all together. Our interpreter told us that was because they expected that from the Americans. We not only required them to intermingle but to utilize teamwork, weight sharing, idea sharing, experience sharing to build the bonds between the two cultures and the two cities.

It was so successful that not only did they come together as a group and do this beautiful 10-minute dance piece, the last day that we were there eating in the courtyard, they were all intermingled together, singing songs together, and the ones that we interviewed said that they had made a new friend.

I would give anything to go back and work more. When we went to Erbil, one of the producers from Reuters filmed all five days and came to the performance we held on the last day. He interviewed families and teachers and dignitaries from the minister of culture, who all said the very same thing -- when are you going to more cities and when are you coming back? This solidified the need for this type of work, specifically in that country -- to go to more cities and to open up not only the lines of communication and diplomacy, but also show the Iraqi people that we want to develop a healing and empathetic relationship between the two countries. That we care about what happens to them after we leave.

The Unique Ability of the Arts To Heal

We've augmented Battery Dance Company's Dancing to Connect and did some research into dance therapy as used with child soldiers and victims of war and we are conducting our first veterans dance workshop at Eastern Kentucky [in July]. We're performing the night before and the next day hopefully some veterans will sign up for our program. It's an experiment.

[Using the arts] allows [veterans] to choose a medium where they can investigate and talk about things that they are going through in a safe environment. At a very basic level, what it allows that veteran to do -- whether in the live poetry setting or dancing or seeing dance or yoga or painting -- is to collect these feelings and to put them in a describable medium for the veteran that he or she chooses, and then to let it go [whether] in a performance or to put it on paper and let it go. Not only to describe it to other people but just to get it away from them.