The Magic of the Arts

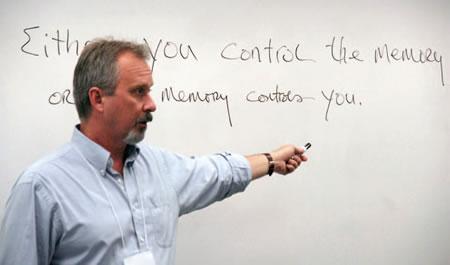

Ron Capps leading a workshop for the Veterans Writing Project, which he founded in 2011. Photo by Jacqueline M. Hames, Soldiers magazine

In 1998, Lieutenant Colonel Ron Capps was sent to Kosovo to work as a diplomatic observer for the State Department. One of his duties there was to write up official daily reports of what was happening in the field, which were then cabled on to Washington.

"We were told to write crisp, dry reports about messy, horrible acts of cruelty," Capps said. "That wasn't satisfying to me. I needed to really capture what I was seeing and what I thought about it. I did that a lot; if not every night, most nights. I wanted to remember."

It was a habit he maintained during the next several years as he was assigned to Rwanda, Afghanistan, Iraq, and Darfur, each one a war zone with its own special set of atrocities. He had seen the bloody results of massacres, been held at gunpoint, listened to stories of rape and mutilation, and dodged rocket attacks. By that point, he said, "I didn't want to remember as much. I wanted to forget. But you can't."

After being diagnosed with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Capps began to self-medicate with Prozac and whiskey. But it was not enough. While stationed in Sudan, Capps, a 25-year veteran, nearly committed suicide. He was later medically evacuated back to the United States and retired from the military. He received his MA in writing from Johns Hopkins University in 2011, and founded the Veterans Writing Project the same year. Today, he lives and works in Washington, DC as a writer.

Capps' journey to the brink is unfortunately not unusual among members of the military today. Approximately 27 percent of troops returning from Iraq and Afghanistan suffer from PTSD, traumatic brain injury (TBI), or both. In the first 155 days of 2012, 154 active duty troops committed suicide -- an 18 percent increase from the corresponding period in 2011. What is unusual, however, is how Capps was able to use writing as a means of healing. He frequently says that he "wrote himself home."

|

|

|

Now he is helping others write their own paths back to wellness at the National Intrepid Center of Excellence (NICoE), located on the campus of Walter Reed National Military Medical Center in Bethesda, Maryland. Open since October 2010, this brand-new facility is pioneering a holistic approach to treating and researching combat-related TBI and PTSD. The patients referred here typically have complex physical and psychological issues, and haven't responded to conventional treatment. During an intensive four-week program, they are treated with a combination of traditional medicine and alternative therapies, including acupuncture, recreational therapy, art therapy, and writing. In June, ground broke on two NICoE Satellite Centers at Camp Lejeune, North Carolina, and Fort Belvoir, Virginia.

The writing component of the program is a new feature of the NEA's Operation Homecoming initiative. From 2004 to 2009, Operation Homecoming conducted more than 60 writing workshops for troops, veterans, and their families, giving these individuals an opportunity to tell their stories. The project resulted in a published anthology of submitted works, as well as two award-winning documentaries. In a new iteration of the program, the NEA has collaborated with NICoE to feature expressive and creative writing in group and individual sessions as part of the center's standard clinical program. Capps was brought in by the NEA to lead the workshops. At the time of publication, plans were also in the works for the NEA to partner with NICoE on a new music therapy program. Like all components of NICoE, both the writing and music programs are designed as cohesive aspects of service members' overall treatment plans.

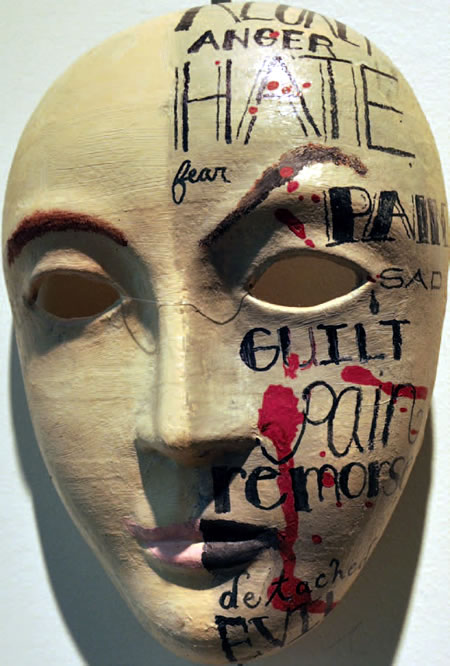

Capps and Melissa Walker, the program's art therapist, have worked together to ensure their programs are integrated and reflect issues that patients will be working through with their other care providers. Both structure their first group classes around themes of masks and identity. Walker begins by having service members create masks, which allows them to visualize and externalize conflicting identities of who they were and who they have become. For his initial expressive writing session, Capps starts with a scene from The Iliad that describes how Hector, while wearing armor, isn't recognized by his own child.

"The service members are coming here because they're trying to figure something out," Walker said. "Their career might be changing. They might have to transition out of the military. They might go back into the military, but not be able to operate the same way. It's confusing for them." On top of that, troops must somehow reconcile their combat identity with their family identity. "You have to keep your warrior in theater, and you've got your family person when you're at home," she said. "Sometimes that spills into each other."

Once patients start creating, both Capps and Walker believe the hypervigilance associated with PTSD can begin to weaken. After 15 months spent on guard in a combat zone, it can be difficult to turn the brain "off" into a relaxed state. With art, "They're finally able to zone in, hone in, and have everything slow down," Walker said. "I think that helps to at least start to reverse some of these effects that [mental] ramping up has had on them."

Although sharing their writing and artwork is not mandatory, it can help build bridges back to both peers and families. Every Wednesday evening, informal creative writing sessions -- accompanied by a barbeque -- are held for all patients and families at either NICoE or the Fisher House (which provides free, on-site housing for troops receiving treatment and their families) as an additional part of the Operation Homecoming initiative. These sessions are supported by The Boeing Company, which has sponsored Operation Homecoming activities since the initiative's inception in 2004.

Those who wish to share their work with the group may do so. "We have a number of cases where family members would just look at us and go, ‘He's never said that before,'" said Capps. "Maybe because he couldn't."

Capps elaborated on what he referred to as "the magic of the arts." "Writing helps to create a little bit of distance," he said. "The way that I think of it is as if you have this traumatic memory and it's hot or radioactive. You pick it up with your bare hand -- your bare brain so to speak -- you can't manage it, it's unmanageable. But by putting art or music or writing in between, you have a filter -- it's like putting on a pair of gloves. You can reach out and pick it up."

Existing scientific research seems to back up this idea. In the 1994 study The Body Keeps the Score, Bessel van der Kolk used neuro-imaging to show that traumatic recall caused the left frontal lobe of the brain to shut down. This is where Broca's area -- the center of speech in the brain -- lives, which would explain why so many individuals have difficulty verbalizing their traumatic experiences. In contrast, traumatic recall lights up the brain's right hemisphere. "Those are the same areas that you use when you're doing spatial reasoning and using your hands and creating something," Walker said. "You're literally accessing the same parts of the brain [that you would] if you were trying to access that trauma."

NICoE hopes to continue to research the effects that the arts have on treating TBI and PTSD. Right now, the art modalities are evaluated anecdotally, but NICoE is beginning to explore how they might be measured scientifically. "We need to figure out what are the measurable effects, and then build those into a protocol," said NICoE Director Dr. James Kelly. Functional imaging, he hopes, will allow doctors and scientists to see "what parts of the brain are used when creating art, and how this helps people psychologically."

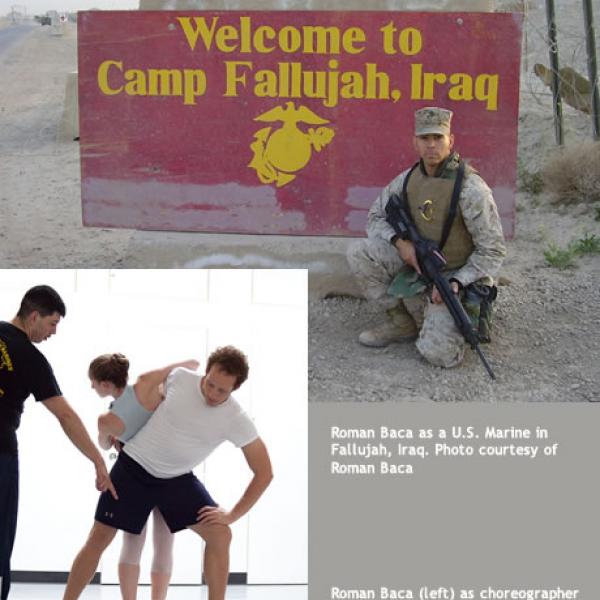

But anecdotal or no, the evidence seems powerful. On July 3, 2010, E-4 Army Specialist James Saylor was hit by mortar fire in Afghanistan. He took shrapnel to the back of his head and neck, part of which bounced off the back of his skull and lodged itself against the jugular wall. One of the discs in his back was broken, and two others were herniated. During a surgery to remove the shrapnel, a nerve was nicked, and the right side of Saylor's face became paralyzed. Diagnosed with PTSD, he found himself plagued by nightmares, impatience, and irritability.

|

|

|

After an unsuccessful stint at the TBI clinic at Fort Campbell, where Saylor is stationed, he was admitted to NICoE in February 2012. All troops are invited to bring their families along during treatment, which was a gift for his wife, Tiffany. When it comes to TBI and PTSD, she said, it's not just about the individual soldier. "You're also healing the family, because that family's got to adjust to it as well."

For James Saylor, it was writing that became a favorite tool to manage his PTSD. "We're trapped in our own heads in these dreams and these nightmares and these flashbacks," he said. "But once we get down into the writing and music and art -- that we can control, and we can do what we want to. We can change it and take it anywhere we want to, whenever we want to." During the creative writing sessions, Saylor began to write a story about dirt track racing; it is now 30-something pages long.

Even though the content doesn't deal directly with his traumatic memories, the story provides a way to channel his feelings in a more manageable framework. "[Dirt track racing] is something that I know a lot about, and I'm not scared to write about it," he said. "I can express my feelings -- my irritability and anxiety -- through my story in ways that I know, that I've seen on racetracks."

Of course, artistic expression isn't effective for all patients; like any other wound, TBI and PTSD heal differently for different people. But for those who do respond, it can be a saving grace during what can be a years-long -- and sometimes lifelong -- recovery. Although Capps retired from the military in 2008 and has gone on to re-shape his career and his own personal story, he said that the therapeutic value of his work still persists as he writes about his experiences in Kosovo, Afghanistan, and Darfur. "I somehow knew that writing was, for me, the way that I was going to get control of my brain," Capps said. "And I did. And I still do."