Reverberations

Listen to 1992 NEA Jazz Master Betty Carter effortlessly twist a melody into an alternate dimension, alchemizing it into a raw, effortlessly virtuosic, and beautifully improvisational mutation of its originally composed form, and you will understand that hers was a voice and creative brilliance for the ages. As singer Carmen McRae, also an NEA Jazz Master, once described, “There’s really only one jazz singer—only one: Betty Carter.”

Talk to any of the scores of ascendant jazz artists sparked forward by Carter’s decades of musical mentorship, though, and you’ll realize that her once-in-a-generation gift for voice and interpretation isn’t her only contribution to echo into the future.

Carter was born in 1929 and laid to rest 69 years later, leaving behind a roster of mentored musicians that is every bit as impressive as the body of work the singer recorded. That list of musical heavyweights includes Stephen Scott, Geri Allen, Don Braden, Mulgrew Miller, Cyrus Chestnut, Benny Green, Kenny Washington, and 2017 NEA Jazz Master Dave Holland—and that’s just the beginning.

Perhaps two of Carter’s most visibly accomplished mentees are bassist Christian McBride and pianist Jason Moran. McBride is a five-time Grammy Award winner who serves in leadership roles for organizations like the New Jersey Performing Arts Center and Newport Jazz Festival and educates students through the organization Jazz House Kids. Moran is a MacArthur Fellow who has been described by Rolling Stone as “the most provocative thinker in current jazz.” He currently leads the Betty Carter’s Jazz Ahead program in his role as artistic director for jazz at the Kennedy Center.

It was in fact through Jazz Ahead, a career development residency program founded by Carter in 1993 in Brooklyn and brought to the Kennedy Center in 1998, that Moran first directly felt Carter’s influence. As a student, he was selected to participate in the Kennedy Center’s inaugural Jazz Ahead class. Along with a small group of fellow young musicians, he experienced what could well be described as an ongoing master class in musical risk-taking.

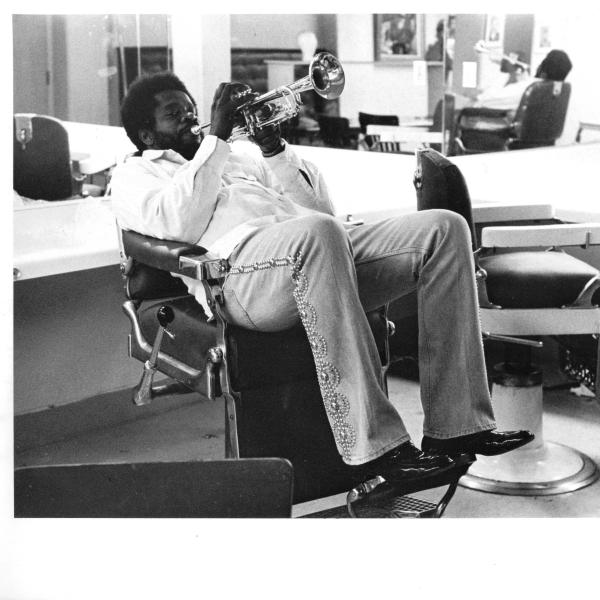

|

“During the two weeks we worked together, she gave me a lot of confidence in the kind of approach I had,” said Moran. “This was around 1998, and my approach was still under construction. I might say I was a bit of an outsider. I proposed to perform a song with three singers, two saxophonists, two basses, piano, and drums.”

Moran’s concept was indeed unusual, and his piece unlike any other on the program. “Some of the other students were whispering that when Betty would hear my song, she was going to tear me apart,” he said. “But when Betty did hear the song, she turned to everyone—at least in my mind she did!—and said, ‘See, this is what you all should be trying to do!’ She had berated many students for bringing in songs that sounded too traditional. She then helped my song out, and it was eventually performed at the final concert. She was proud and supportive, and I never forgot that.”

According to McBride, Carter’s passion for giving opportunities to younger musicians such as himself and Moran and supporting their explorations was a two-way street, and one that paid all parties back in creative dividends. Carter herself once stated that she “learned a lot from these young players, because they’re raw and they come up with things that I would never think about doing.”

“She herself always stayed fresh by having young musicians around her,” said McBride. “It was 50-50, and that comes from a long line of mentorship in music, particularly in jazz, but in classical music as well. It’s not like a rock band where you get four musicians, try to make some hit records, and never break up…. In jazz, we have to make sure that all of these great musicians out there get an opportunity to get heard and better themselves, express themselves, and develop their skills. Betty is part of a long line of mentors in the history of jazz.”

McBride first became aware of Carter during his pre-teen years, when he was initially discovering the music that would shape his career and artistic journey. It was hard to miss the iconic singer, he said, when being taught about the legends who shaped the legacy of jazz.

As a first-year student at the Juilliard School of Music in New York City, McBride received an invitation to join Carter’s trio, a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity that thrilled him—but was unexpectedly lost due to an unfortunate miscommunication about who was supposed to call whom once Carter returned from a European tour. In 2017, McBride laughed about the crossed wires that cost him the seat in the band. Though Carter ended up hiring another bass player at the time, she and McBride went on to play together on many occasions, becoming close friends up to the time of the singer’s death.

Having supported her on the bandstand so many times, McBride described Carter’s approach as a truly original variation on the jazz vocal theme. “Most jazz vocal albums are highly polished, highly stylized, with nice, tight arrangements,” he said. “Now, Betty always had nice, tight arrangements and great musical directors, but the way that Betty sang was so unorthodox with her sense of rhythm and timing. Even her sense of intonation was so unusual that you were drawn in by its unusual-ness. I don’t think we’ll ever see another singer like Betty ever again.”

Throughout the years, McBride saw Carter’s impact on younger musicians like himself first-hand. “Betty would police us,” he said with a laugh. “There was a certain generation of jazz musician who would come and listen to the younger musicians play and give them a report card after almost every set. When Betty came into the club—Bradley’s, the Village Vanguard, Sweet Basil, wherever it was—everybody onstage sat up a little straighter, played a little harder, and paid a little more attention. Betty commanded that respect. I miss her dearly.”

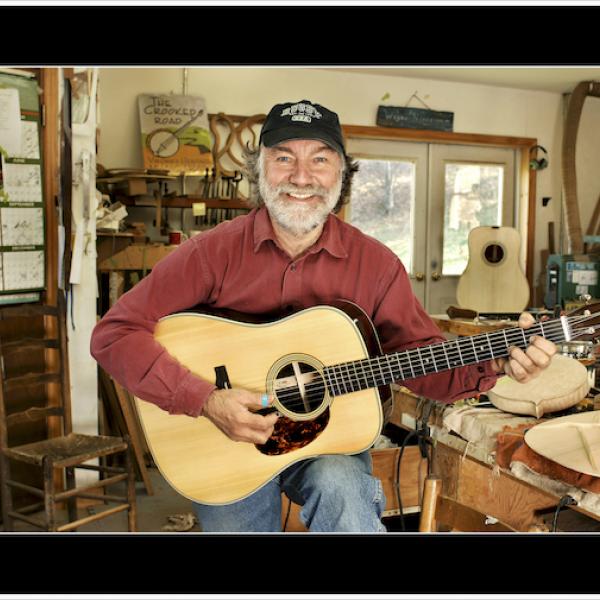

|

To Moran, Carter’s attention to the rising generations of jazz musicians was a mixed matter of present and future, personal and global. “Betty seemed to be ultimately concerned about the health of jazz and the musicians that create it,” he said. “I think she fought insanely hard for her place in the canon, and knew that another way to ensure this was to influence the new crop of musicians. She left a lot of seeds with us, and we continue to place them carefully into the soil.”

Case in point, Moran continues to channel Carter’s guts, brilliance, and spirit in his work running Betty Carter’s Jazz Ahead. “I only hire faculty members that worked with Betty,” said Moran. “This ensures that we all know the vibe Betty had during Jazz Ahead, and we keep up the intensity.”

“In our past four years, the students continue to shock us, and what we now understand is that we are making an enormous family,” he continued. “These students really know each other after two weeks of working together. We become a family and we never forget these bonds. It’s very emotional because I hope this is what Betty intended, as it is extremely powerful work.”

Michael Gallant is a composer, musician, and writer living in New York City. He is the founder and CEO of Gallant Music.