The Weaver in My Poems

In my poems, Em Bun weaves night and day, mourning the disappearance of her firstborn son. She weaves using her own hair—long, silver strands that grow out of grief. Seeking refuge in her loom, she works tirelessly.

The persona of Em Bun in my poetry is not so far from my real grandmother, my lok yeay. A traditional silk weaver, she didn’t use her hair to weave; she used silk scraps donated by a local tie factory in York, Pennsylvania. As a child, I’d watch her in the basement as she pushed the rows of weft into the warp, passing the shuttle back and forth, and this back and forth now makes me think of her struggle as a refugee in America. I used to strum the tightened threads like guitar strings or play with cones of silk that she skillfully rolled from skeins. But I didn’t know of the hours she spent preparing the silk, the hours she privately grieved her son, Samon, lost to the Khmer Rouge. I miss the sounds of her floor loom, her feet stepping on the treadle—these wonderful rhythms she created in her home. Little did I know of her depression or the isolation she felt when she resettled in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, her new home. I wonder what she would think of me now, writing poems about her in English, a language she did not speak.

***

Last December, the National Endowment for the Arts announced the recipients of the 2017 Creative Writing Fellowships while I was visiting Cambodia. I was among those poets, both honored and shocked by this award.

As I walked around the riverside in Phnom Penh, I remembered the framed certificate with a large, silver “A” hanging in my grandmother’s living room and in smaller print, the words: Master Traditional Artist. In 1990, she had won an NEA National Heritage Fellowship. In a photograph, she holds this certificate. She doesn’t look directly at the camera, but she is proud and fully present. In my motherland, I broke down and understood what lok yeay and I shared.

***

Born and raised in the village of Chambak, Takeo province, lok yeay learned to weave from her mother at the age of 16. In her youth, she considered it a hobby and family members would buy her silk to make traditional skirts, outfits for weddings or special holidays like Pchum Ben or Chhnam Tmei—the Khmer new year in April. Though her mother wove intricate diamond patterns, a preferred style for elders, lok yeay emphasized solid, shiny colors in her craft, a style more appealing for younger women.

What I wish I could steal from my grandmother’s artistry is the tapioca mixture she boiled overnight with coconut oil and other ingredients my mother and aunts have long forgotten. She would dip her fingers in the tapioca and sweep it across the silk, then take out any clumps with a brush. Fabric, like hair with added oils, needed to be combed out. This technique allowed her to thicken the material and create a gorgeous, soft luster.

|

Through poetry, I want to recreate her process. I want to dye words like colors and establish a unique texture on the page, like she did with silk. Turquoise. Cherry red. Gold. These were the colors lok yeay was known for. At Cambodian weddings in Cleveland, Ohio, where her relatives lived, she wore her own fabrics, showing off dark purple hues while my mother donned a traditional golden skirt. Touching the fabric, several Cambodian women would ask, Where did you get this? and lok yeay would return home with orders of 100 yards or more. Many of her clients were local, from Hershey and Lebanon, but many others lived in Washington, DC; Lowell, Massachusetts; upstate New York; Louisiana; and Canada. Cambodian refugees took pride in lok yeay’s weaving. Her craft insisted on the preservation of Cambodian culture in a new country. I wonder how many Cambodians got married wearing my grandmother’s silk, how many lives she touched by connecting them with our culture.

***

As a poet, I pay attention to the stories that my family repeats. When my mother recalls the evacuation of Phnom Penh on April 17, 1975—a day that many Cambodians remember—she likes to recall her experience of walking with lok yeay, behind the rest of the family. Side by side, they walked the same pace. Those three years, eight months, and 20 days, lok yeay looked after our family and helped them survive. She held out hope for her eldest son, Samon, a lieutenant captain under the Lon Nol government who had been training in the United States. A few months before the decline of the Khmer Rouge, her husband died from forced labor and disease. She fled to Khao-I-Dang refugee camp in Thailand, and there, she and our family were sponsored by a Presbyterian church in Harrisburg. She was 65 years old when she resettled in the United States in 1981. She hoped to see Samon. Once she arrived, she learned that he had returned to Cambodia long ago, at the onset of the war.

***

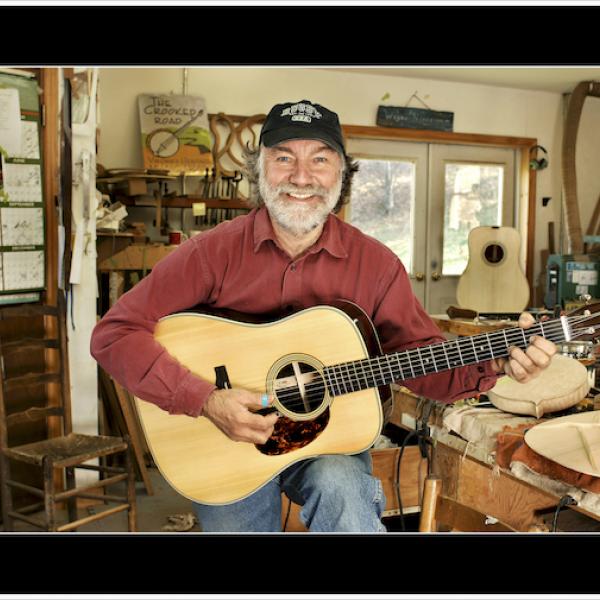

Lok yeay stayed home alone while her daughters worked at a sewing factory downtown. She struggled with depression. She tried weaving with an American loom, but the feeling was not familiar to her. With the help of Joanna Roe, a woman from the Presbyterian church, a craftsman built a Cambodian-style floor loom for her. In 1982, she picked up weaving again and this helped her move toward healing.

Recently, I found a short video clip of her online. Onstage at the NEA National Heritage Fellowship Concert in 1990, lok yeay tells the audience in Khmer, Pir thngai. Two days. She took two days to weave this plaid fabric. From her lap, she takes the folded red and green design and opens it wide for the audience to see.

|

Weaving gave my grandmother a vocabulary so fine and textured, anyone could understand her story just by touching or eyeing her bright silks. She didn’t know how to speak English fluently. When the phone rang, she’d pick up when nobody was around and say, Hello. How are you? And if the caller talked too much, she’d hang up. She would say the same line to me and my cousins as we played in the basement, where she used to weave. There was a time when she could only stand at the top of the stairs, when she was too old to come down to her loom because her knees ached, because she could have fallen easily.

We could not speak to each other fluently in either English or Khmer. Often times, I would watch her and she would watch me. She would give me something to eat or call me to her garden, and I would hold her hand. She was the weaver in my family, and I am the poet. When I visit her house, I enter her old bedroom and open the closet door to find the silk fabrics she made herself. I look closely at the skirts and know that she dyed two colors and wove them together, so a third color could shine.

Monica Sok is the 2016-2018 Stadler Fellow in Poetry at Bucknell University and the recipient of a 2017 NEA Literature Fellowship in Creative Writing.