Donald Byrd: Well, my uncle was a drummer and I started playing drums, but it didn't make no music to me, and I said, "Man, I can't use this." And so I wanted to play trumpet.

Thank You…(For Funking Up My Life) up

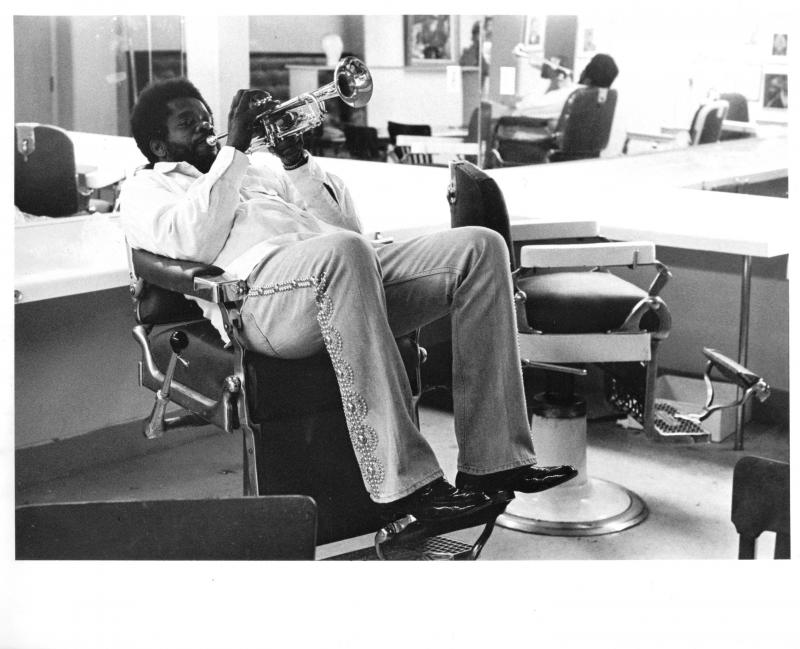

AK: THAT WAS TRUMPETER AND NEA JAZZ MASTER, DONALD BYRD. BYRD GREW UP IN THE 1940S AND 50S WHEN DETROIT WAS A MUSICAL HOTBED, EXPOSING HIM TO AN ENDLESS NUMBER OF JAZZ MASTERS AND CHARTING THE COURSE OF HIS INCREDIBLE LIFE.

Donald Byrd: Milt Jackson, Sonny Stitt, the Jones brothers—Elvin, Thad, Hank. Tommy Flanagan I grew up with. Barry Harris I came up with. Curtis Fuller I came up with. Joe Henderson. Yeah, I don't think you got enough time for me to deal with that. <laughs>

HIS CONNECTIONS WERE ALMOST AS INFINITE AS HIS THIRST FOR EDUCATION. BYRD NOT ONLY EARNED 6 GRADUATE DEGREES BEFORE HE LEFT THIS EARTH IN 2013, BUT HE STARTED THE JAZZ STUDIES PROGRAMS AT THREE COLLEGES INCLUDING HOWARD UNIVERSITY IN WASHINGTON, DC. IT WAS AT HOWARD, WHERE HE FOUNDED, SHAPED AND PRODUCED THE INIMITABLE BAND, THE BLACKBYRDS. TODAY, WE’LL HEAR ABOUT BYRD’S IMPACT FROM THE BLACKBYRDS’ DRUMMER, KEITH KILLGO. THREADED THROUGHOUT KEITH’S COMMENTARY, WE’LL HEAR PIECES FROM AN INTERVIEW WITH DONALD BYRD CONDUCTED BY JAMES GRAVES FOR PACIFICA RADIO. BYRD WAS MANY THINGS. SCHOLAR. PILOT. TEACHER. JAZZ MASTER. TRAILBLAZER. IN FACT, DONALD BYRD CHANGED THE GAME WITH HIS 1973 ALBUM, BLACKBYRD, WHICH AT THE TIME WAS THE BEST-SELLING ALBUM FOR BLUE NOTE RECORDS. THE FUTURE BLACKBYRDS WERE HIS BAND. KEITH KILLGO.

Keith Killgo: He was a force in that whole genre of music.

Black Byrd up.

Keith Killgo: Black Byrd was originally recorded for Lee Morgan. And then, unfortunately, Lee Morgan was killed, and they needed to find someone to do it. And that’s how Byrd got Black Byrd, because the Mizell Brothers had already recorded it.

And believe it or not, if you look at it historically, Herbie Hancock, which was one of his protégés, as well; Everybody started putting groove and funk groove. Harvey Mason probably made more money as a drummer than anybody in show business at that time, because he played on Mister Magic and Black Byrd, and Carole King—everybody. Because that groove, that feel, had changed for jazz. Jazz was no longer boom-boom-boom-boom, boom-boom-boom-boom, boom-bom. It was no longer that. And it had more repetition. But it gave you an opportunity to play even more things, when you really think about it, because there’s a lot more room, because it’s not filled up with a bunch of chords, open chords, very basic chords: triads and sevenths and ninths; you know, something that you could solo through for hours--vamps--which basically came from who? James Brown. Okay?

So if you combine the jazz piece with the James Brown vamp, and you stick some 15-, 16-year-old guys on top of it, then that’s...that’s the formula. <laughs>

I first met him at the Left Bank Jazz Society in Baltimore. And I was playing with my dad, of course, in another band, and Donald, Keter Betts... and I can’t remember who else. Reuben Brown and a few other people were in the band, and so Byrd was like, “Hey, man, I like the way you play. What’s going on? Where you going to school?” And I had already gotten accepted to a school in the Midwest--Bradley University, in Peoria, Illinois. And so he said, “Well, you gonna go to Bradley? Why don’t you go--?” Because he was at Howard. He says, “Why don’t you come to Howard?” “Well, I wanted to get out of D.C., you know? So I left, and that was kind of how we first met. And then I went to Bradley for two years, and then I met Kevin Toney, who I met over the summer here in D.C. He’s from Detroit, and of course he was one of…Byrd brought him here to play and to go to Howard. And so Kevin ended up living with me. So two years went by, and the next thing I know, Byrd is like, “Okay, you’re coming to Howard.”

Donald Byrd: I was one of the first, I guess in jazz education and helped to popularize that since the late fifties. And I was working with the Dave Brubeck and Stan Kenton and all of those people. And we were legitimizing jazz education. Billy Taylor was involved. He was really one of the first people that got me involved right after I came out of the air force. We were frat brothers. And Billy was into that too. And so I helped to establish three major departments in this country, the one at Rutgers University which is still going and they’ve got a graduate program. That’s a big one. The one at Howard, which is even bigger. And the one at North Carolina Central.

Keith Killgo: The Jazz Studies program is really what he kind of brought to Howard. Howard University, originally, is classical music, and people had to sneak out and play jazz on the weekends, or whatever, because that school wasn’t about that. He brought that to the university, and along with that, how to not make this just going to school for four years for music. Okay, well, so what? So you went to school for four years. Then what? Looking at it from a professional perspective, like doctors do. You go do internships to go get what? A job as a doctor, and that’s because that’s what you went to school for. And so that was the whole thing behind having young musicians come in, learn all their craft, and then go out and find work and become a professional musician. And he couldn’t do it with the entire university so he selected several guys to sponsor, so to speak, and kind of drive that dream he had.

What he did first is he got these established jazz artists for a week maybe if that lasted that long. Because the old guys and the young guys…didn’t work. And so Byrd said, “Okay. All right. Guess what? I’m getting rid of the old guys. Bye!” <laughs> And so he fired all those guys. And Kevin said, “Hey, man, we got a gig! Da-da-da-da-da!” He could see, like, “There’s a connection these guys have. And as an established artist, I mean, the kids aren’t listening to the music I’m playing.” You know? And so he saw that, you know, as he brought in Barney and Joe and all of us together, that we had this energy that was related to our age group. So we had that experience and this was the turnaround of the whole music piece because people wanted to dance. If you want to get young people involved in jazz, it better be something that has a beat to it, regardless of what you play on top of it. So he had all the slick notes and all of the musicality piece. The soul of it wasn’t of his generation. So that’s what we kind of brought to the table. And when he saw that start to work, he was like, “Oh, yeah! This-- yeah! I got this!” <laughs> You know?

Do It, Fluid up and hot

Keith Killgo: He was an educator, a musician, who never ... he never stayed still. He was always looking for something else in music. But he got a lot of worldly knowledge, because he has interests in more than just music. But he uses those interests included in music, culturally, about black culture, about history.

Donald Byrd: I got about three thousand books on black history, rare books from the 1700s, slave codes and stuff like that … my father was a negrophile. A man who was crazy about everything. A man who was crazy about his culture, his people, about everything

Keith Killgo: He brought all of that. I mean, he was very fluent in a couple foreign languages, as well. He spent time in Paris.

Donald Byrd: I studied with Nadia Boulanger who is one of the greatest theoreticians. And people like Stravinsky on up was associated, Aaron Copland, Michel Legrand, Quincy studied with her and Gigi Gryce. So not only did I get lessons from Miles and Dizzy and everybody else but I also knew all of the classical players.

Keith Killgo: And then the other part of the education was, we had to look up artists outside of our genre of music: Jacques Ibert, a famous French saxophonist and write out his solo, so that you understand orchestration in a different way than just the way we do what we do; which is okay, but there’s so much more music. So he created that kind of a thing, which made us learn more.

Donald Byrd: My father taught me about the history of my family, about who I was, where I came from, and with him being a United Methodist minister, it was always, it was expected of me to perform and to act a certain way, and I had to. I was born into it. I didn't have any choice in the matter. And it reminds me of something that, a saying that I saw not too long ago: "To whom much is given, much is expected."

Cristo Redentor under

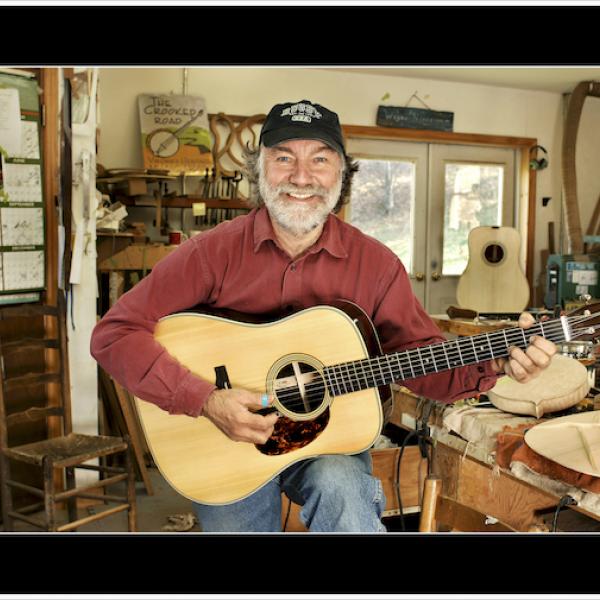

Keith Killgo: And that’s why I’m involved in education. Because if you can’t pass this stuff on to the young people, I mean, I’m not sure what good it is. We can sit around and write books about it, but if they don’t read the books, then they’ll never know. So the firsthand knowledge, you know, bringing up young folks-- I’ve got a singer singing with us now, Paul Spires, and he was one of my students when I was a teacher in D.C. public schools. We wrote a song that’s on Gotta Fly, called I Need Your Love. It took us two years to do. I’d written the music, and he finally graduated. And so I’ve taken him to Europe. He’s gone to London. We’ve gone to Spain and all these places. And that is how this thing lives. And that was Byrd’s whole piece, you know, instead of taking one guy—because he took Herbie Hancock and got him started in moving in the direction he was moving in. But he’d rather do it, rather than for one guy, to do it for a group of guys. And so we were that part of that next piece of it. That ideology, I’m a firm believer, and I will live my life, you know, pursuing that because I really think if you touch one guy, two guys, whatever, it’s got to grow. It has the ability to live. We have to move more bodies in this business, and then that was Byrd’s philosophy, is … so there’s the five guys here. Next time, 10. And next time, 20. Because that’s what carries the legacy.

Adam Kampe: THAT WAS EDUCATOR AND DRUMMER FOR THE BLACKBYRD’S, KEITH KILLGO, ON HIS MENTOR AND NEA JAZZ MASTER, DONALD BYRD. THE EXCERPTS YOU HEARD OF BYRD COME FROM A INTERVIEW CONDUCTED BY JAMES GRAVES. THE AUDIO IS PART OF THE PACIFICA RADIO ARCHIVES FROM THE VAULT SERIES WHICH WAS PARTLY SUPPORTED BY THE NEA. ALL THE MUSIC CREDITS ARE IN THE TRANSCRIPT.

FOR THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE ARTS, I’M ADAM KAMPE

Music Credits:

All off the following performed by The Blackbyrds

Excerpts of Thank You For (Funking Up My Life) composed by Arthur Posey, Josef Powell, and Kevin Toney, from the album, Thank You For (F.U.M.L), used courtesy of Rhino/Elektra/Warner and by permission of Blackbyrd Music, Art and Josef Music (BMI) and K-Tone Music (ASCAP).

Excerpt of “Do It, Fluid” composed by Donald Byrd, used courtesy of Concord Music Group and by permission of Elgy Music (BMI).

Excerpts of “Blackbyrds’ Theme” composed by Allan Barnes, Sylvester Hall, and Kevin Toney, and from Happy Music: The Best of The Blackbyrds, used courtesy of Concord Music Group and by permission of Blackbyrd Music (BMI) and K-Tone Music (ASCAP).

Excerpt of “Gotta Fly” composed by Keith Killgo, Jon Malone, and Allan Barnes, from the album Gotta Fly, used courtesy of K-Wes Indi Productions and by permission of Khempera Music Publishing (ASCAP) and Blackbyrd Music (BMI).

Excerpt of “Black Pearls” composed and performed by John Coltrane, from the album, Black Pearls, used courtesy of Concord Music Group and by permission of Jowcol Music c/o SHUKAT ARROW HAFER WEBER AND HERBSMAN [BMI].

Excerpt of “Black Byrd” composed by Laurence Mizell and performed by Donald Byrd, from the album Black Byrd, used courtesy of Blue Note Records and by permission of Alruby Music Inc. c/o Almo Music Group (ASCAP).

Excerpt of “Cristo Redentor” composed by Duke Pearson performed by Donald Byrd, from the album, A New Perspective, used courtesy of Blue Note Records and by permission of Gailantcy Music Company (BMI).