MUSIC CREDITS:

"Green Chimneys" from the album The Thelonious Monk Songbook performed by the Roy Haynes Trio. Produced by U-5, 2013.

"If I Should Lose You" from the album, Out of the Afternoon, performed by The Roy Haynes Quartet. Produced by Impulse! Records, 1996.

Variation on a Theme by Igor Stravinsky from the CD, Legacy, written and performed by Gerald Wilson. Produced by Mack Avenue Records, 2011.

"Yard Dog Mazurka" from the album, The Jimmie Lunceford Collection, performed by Jimmie Lunceford. Produced by Fabulous, 1947.

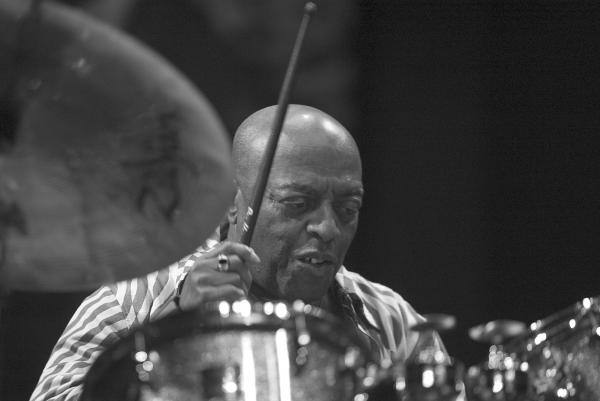

Jo Reed: That's drummer and NEA Jazz master Roy Haynes playing Green Chimneys. And this is art works the weekly podcast produced by the National Endowment for the arts, I'm Josephine Reed.

We're kicking off the fourth of July weekend with a jazzy double feature...later on in the show, trumpter, composer and bandleader NEA Jazz Master Gerald Wilson

But , first.... Roy Haynes defines the word style in every sense: from his distinctive drumming to his snappy clothes--he is first among equals. Haynes is among the most recorded drummers in jazz, and in a career lasting more than 60 years, he has played in a wide range of styles ranging from

swing and

bebop to

jazz fusion and

avant-garde jazz. He's been equally successful as a leader and as a sideman--playing with the who's who in the jazz world. Artists like Charlie Parker, Lester Young, Thelonious Monk, Miles Davis, Danilo Perez, and Christian McBride to name only a few.

Haynes is a notoriously tough interview--not for the faint-hearted--but he's also very insightful about his music and had a surprising amount of patience when he sat down with me at Jazz at Lincoln Center. Here's an excerpt of our talk.

Jo Reed: You got your start with Luis Russell.

Roy Haynes: Uh-huh.

Jo Reed: How did that happen?

Roy Haynes: It happened by what I was doing, and the way I was doing what I was doing. People talked about that, because Luis Russell didn't know anything about Roy Haynes until people told him. And then I was living in Boston at the time, I got a special delivery letter from New York from Luis Russell. He had never heard me, but he heard about me. And I guess it's probably the people that told him about me for him to stretch out and try to reach me, which is the way it happened.

Jo Reed: One of the first gigs you played with him was at the Savoy.

Roy Haynes: The first gig was at the Savoy.

Jo Reed: It was the very first. What was that like?

Roy Haynes: What was that like? It was…

Jo Reed: What was the Savoy like then?

Roy Haynes: The Savoy, you can't hardly describe it in anything that you'll know about, you've got to have a great imagination because a lot of people would come to the Savoy Ballroom, and they probably wouldn't even dance, there's so much excitement going on. First of all, they had two bandstands. They usually have a big band on one bandstand, and a small band, a combo, on the next bandstand. Back in probably the late '30s, early '40s they would have the battle of the bands. So there were two bands, they'd be battling. I used to hear a lot about it when I was young, in Boston. Because I think certain nights they would broadcast anyhow, from the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem to different stations, so I had heard about it then. When I first played there with Luis Russell's band I don't think the bands were really battling then, because it'd be a big band on one side; twelve, thirteen, fourteen-piece and a small combo on the other side, the other part of the bandstand, which was like twin bandstands together. But that was really an exciting period, because not only the people came to dance, some people would just stand in front of the bandstand and listen. They call that the "home of the happy feet" because people will-- a lot of people could dance like they were professional in those days, '40s, was when I first come to New York with the band. My first job, like I was saying, was at the Savoy Ballroom in Harlem. So it was a very exciting period.

Jo Reed: And as you said, Luis Russell of course had a big band.

Roy Haynes: Yeah, we had, I don't know twelve or thirteen-piece orchestra; three brass, maybe three trumpets, three trombones, three saxophones, three or four saxophones, and a guitar, and bass, and drums, and a great vocalist.

Jo Reed: Who was the vocalist?

Roy Haynes: Lee Richardson when I was with the band. He made hit records. One of his big records was "The Very Thought of You." He has this voice, "The very thought of you, and I forget to do…," and all the young girls would be screaming. We'd play theaters like the Earle Theater in Philadelphia, and we'd do five shows a day during that period.

Jo Reed: Five shows a day.

Roy Haynes: Oh, yes. And if they had a lot of people waiting in lines after each show, they would have to add another show to it. So you got a chance to make extra money, then. The more shows you did, the more money you made. And a lot of that wasn't always planned in advance. Sometimes it would just happen when it would happen, the last minute. People would be lined up to come in the theater waiting for people to leave so they could come in and catch the show.

Jo Reed: How important do you think that experience was for you as a performer, especially backing a-- playing in a big band?

Roy Haynes: Well, it was my first big band experience for one thing, which is something I wanted to do anyhow because I used to listen to a lot of the big bands like the Basie band when he had Papa Jo Jones playing drums. And also when he left they had other younger drummers that I would go and catch with the band. In fact, I did get a chance to play with that band a couple of times when I was much younger, also. But I was never a steady drummer with the band. I just filled in for a few nights.

Jo Reed: And Papa Jo Jones is one of the drummers that you listened to.

Roy Haynes: Oh, definitely. He was the main one. In fact, a lot of drummers my age during that time, in fact drummers of any age, usually were checking out Papa Jo Jones.

Jo Reed: What was it about his sound?

Roy Haynes: Not only his sound, his feeling, and the way he would do different things. It's hard to explain, because I'm talking about early '40s. I'm just beginning to be a professional drummer, and I'm listening to certain things that other drummers didn't do, and the way he would do what he did. The feeling came from here, it wasn't nobody to just practice. This was a natural drummer, which is what they told me I was. I was just born a natural drummer, so I could sort of relate to Papa Jo.

Jo Reed: You saw the birth of bebop. Did it grab you right away when you first heard it? Was it like an explosion in your mind when you first heard it?

Roy Haynes: Well, I don't know if I would look at it as an explosion, but it was something new that was happening. The tunes, like the compositions, and the way the different artists were playing, certain artists, the things that they were doing musically, yeah, it was something new, so it did grab me, yeah. I jumped right on it, yeah.

Jo Reed: And you played with Charlie Parker.

Roy Haynes: Yes, Charlie Parker hired me, I forget what year it was, 1949 I'm thinking, yeah. And I was with Lester Young during that period. And I know once there was a gig, a concert, in I think Baltimore, Maryland where there were two bands; Charlie Parker's band-- I was with Lester Young then. And Charlie Parker was there with his band, and his drummer at that time was Max Roach. So Max Roach's drums were set up on the stand, on the bandstand. And I said, "I'm going to sit my drums right beside his." Max was very popular then. And I was a young guy-- younger guy, a couple of years younger than him, just beginning to get popular also. So I said, "Yes, I'm going to set my drums right up next to his," and I did, and not even realizing that I would end up playing with Charlie Parker. I was with Lester Young then. And that was a great time of my life with the music, and a great experience to be playing with Lester Young opposite Charlie Parker.

Jo Reed: I would think it would be.

Roy Haynes: Oh, yes. That was a very exciting period.

Jo Reed: I seem to remember people saying Lester Young spoke in a very particular language. He was very funny, but you kind of had to understand where he was coming from to get what he was saying, is that-- did you find that to be the case?

Roy Haynes: Yeah, that was very true. Lester Young, he was one of the most, how can I describe him so people will understand, original people that I have ever met, not only in the way he dressed, the way he talked. He would talk-- if he just met you, he would talk his language to you. So some of the things you probably wouldn't understand what he was saying. But that's the way he was. He was a very original person all the way; the way he played, the way he dressed, and the way he talked. And it was not just a put-on thing, that's the way this man was.

Jo Reed: Were you sorry to leave that band and go with Charlie Parker in some ways?

Roy Haynes: I was happy because I wasn't just moving on to move on, I was going to be playing with Charlie Parker, one of the great persons. I went from Charlie Parker to Sarah Vaughan. it was great playing with Charlie Parker. He was a great genius. Sarah Vaughan was a genius also. They did a recording together that also inspired me. Charlie Parker was on a recording with Sarah Vaughan. Sarah Vaughan, I mean, she could just-- she knew the music, too. She knew the chords, the changes that she wanted the musicians, especially the keyboard player, to play for her. We have a lot of people that are great singers, but they don't always know the music or about what they're doing, they just do it naturally only, and they're gifted to do it that way. But Sarah Vaughan, she could pick up the music and read the music as well, a new composition that she never heard before. One of the differences of just playing with somebody who can sing, and not a great musician, but Sarah Vaughan was a great musician as well.

Jo Reed: You were with Thelonious Monk at the Five Spot with a great live recording. I think it was '50--

Roy Haynes: Late '50s or '60s, Yeah.

Jo Reed: What was it like playing with Monk?

Roy Haynes: It was great. I enjoyed it. I enjoyed every moment. Little Monk wasn't just an ordinary artist. He had a lot of feeling, a lot of imagination, and it was great. It was great playing with him. Only thing that was kind of strange, sometimes you had to wait hours before he would show up, so we wouldn't play until he arrived. So sometimes the club would be crowded with people waiting for Monk to come. But that was a long time ago. That was in the late '50s. That was yesterday.

Jo Reed: That was yesterday. Jazz has a reputation, rightly or wrongly, of being not a young person's music anymore. I'm often in audiences, and I always look around to try to see how old people are in the audiences, and they tend to be older audiences. And opening jazz up to younger people seems to me to be something that is a very significant thing to do, and that is something that you do. Your audiences, the demographics tend to be more skewed. I'm not saying they're all young by any means, but they do tend to be more skewed.

Roy Haynes: You're absolutely right. That's something, huh.

Jo Reed: I think so.

Roy Haynes: It's something for me to think about, too. Yeah. I think about it. Yeah, I really-- because sometimes I don't notice it right away. I know I've heard people say years ago, I'm not talking about the last two years, but even before that, "You draw a really young audience." Fifty years ago would say that about me, when I was much younger than I am. So I guess that has to do with the music, or the feel of the recordings, or something they heard or read about my music or something. I don't know. I'm one of the ones that-- I don't analyze things. I don't try to. Some of the-- a lot of the things that happen I just keep on keeping on, and don't try to figure them out. That's what I do on the bandstand, too, a lot of times. If I try to really figure out the music, boom, boom, boom, boom, boom, I try to do it by what I feel rather than talk about it. Even if I have somebody new in my band, I don't sit down and tell them what I expect them to do, what I would like them to do. Usually they probably feel something, or heard from some way-- we don't talk about it much. And it works. It has been working. So I'm going to leave it alone…

Jo Reed: That's drummer and NEA Jazz Master Roy Haynes. This is Art Works, I'm Josephine Reed.

Gerald Wilson is a storyteller as well as a jazz legend-- and as a composer and bandleader for sixty years, he has quite a few tales up his sleeve. Gerald Wilson's use of multiple harmonies is a hallmark of his big bands. His band was one of the greats in jazz, leaning heavily on the blues but integrating other styles as well. His arrangements influenced many musicians, including multi-instrumentalist Eric Dolphy who even dedicated a song to him. Wilson's career took off in 1939, when he joined the

Jimmie Lunceford orchestra where he honed his skills as a musician, composer and arranger

. In addition to being a band leader and composer, Wilson has written arrangements for many other prominent artists including

Duke Ellington,

Sarah Vaughan,

Dizzy Gillespie,

Ella Fitzgerald,

Benny Carter, and so many more. For many years he was a popular teacher at various California Universities, spending over twenty years at UCLA where he taught jazz history. Wilson's also a great admirer of classical composers--and his recent cd

Legacy contained an homage to Igor Stravinsky. When i spoke with Gerald Wilson at Jazz at Lincoln Center, I asked him to tell me about

Variations on a Theme by Igor Stravinsky.

Gerald Wilson: For many years, I've been a classical admirer of classical music. My sister was a classical pianist. So I've heard a lot of classical music. And these are some of the special people that I like, like Igor Stravinsky. And I saw him in person, myself.

Jo Reed: Really?

Gerald Wilson: Yeah, amazing. I saw him at the Hollywood Bowl back in the '50s. And he was there with his son, Soulima, who was the featured pianist, as he conducted that night at the Bowl. And it left an impression on me. When you make a variation, you don't actually do the whole piece. For instance, the Stravinsky piece, I only use six notes out of the whole "Firebird" ballet.

Jo Reed: Only six notes? And yet, you...

Gerald Wilson: There are only six notes. But you use the six notes, which is the essence of the piece. And then, we change the form of it from what it was to a jazz piece, by changing the form.

Jo Reed: You have had one of the great careers in music.

Gerald Wilson: My musical career started with my mother, who taught school in the little town we lived at, and it was called Shelby. And she was the music teacher. And she started me out, at the age of four, as she did my sister and my brother. My sister was a classical pianist only. And my brother, he also played the piano. He played some classic. But he can also play jazz. And he graduated from Tuskegee...

Jo Reed: With Jimmie Lunceford?

Gerald Wilson: Yes. This story starts from Chicago. I went to Chicago at the World's Fair in 1934.

Jo Reed: Whoa.

Gerald Wilson: And I was amazed by Chicago because having lived in the south all my life, in Chicago, when I got on the street car, I didn't have to go to the back of the street car. And I said, "Well, gee, this is nice. It's a good feeling." So when I got back home from the World's Fair, I told my mother, I said, "Mother, I wish you would send me to Chicago to go to school because I like what's going on in Chicago." So she said, "Well, listen, I don't think I can send you to Chicago." But she said, "I can send you to Detroit." So I said, "Well, as long as it's in the north." So then, she sent me to Detroit. Well, that morning when I went to school the first day in Detroit, it was not segregated school. It was all kinds of people in the school. And that was in all the schools in Detroit. There were no segregated schools in Detroit. All of those were open to black students, as well. There was no segregation in any of the schools or universities and colleges in Detroit, Michigan. So I said, "Well, now, this is really a wonderful place." Because it gives you another feeling, if you come from a place like Shelby, Mississippi.

Jo Reed: Early in your career you played with Jimmie Lunceford. Tell me about it.

Gerald Wilson: Jimmie Lunceford? First of all, Jimmy Lunceford was a fine musician. He played flute. He played the saxophone. He could play the guitar. And he could also write music.

Jo Reed: With Jimmie Lunceford you began composing, you began arranging. One of the songs you did for him was "Yard-dog Mazurka".

Gerald Wilson: Yes. "Yard-dog Mazurka" was a number that I composed and arranged. What happened was-- fooling around with the piano one day, I had learned this chord progression that had never been used by any band in the world. And it starts right out from the beginning. But it happened just by chance. There was a young man by the name of Roger Segure, a young white fellow there that wrote music for Jimmie Lunceford. So I was over to his home in New York, right in New York, and he was writing music for the Lunceford Band at that time. And so I was at his home one evening. And I said, "Hey, Roger, listen to my introduction I'm making on 'Stompin' at the Savoy.'" And I played in terms of n the piano for him. And he said, "Gee, that's really a great chord progression you've got there." But he says, "You know what you ought to do, Gerald?" He said, "You should just repeat that eight bars and then, write yourself a bridge, which is another eight bars. And then, repeat the eighth." That's why they call it the AABA form. So I thought about it. And he told me, he said, "You should do that and then you'd have a composition of your own." So the next day when I saw Roger, I said, "Roger, that's a great idea you told me." And I said, "I'm going to give you half of the number." I did. I gave him half of that number. That's why you will see on it, "Gerald Wilson and Roger Segure." And that's the honest thing I did.

Jo Reed: Well, Gerald, after you left Jimmie Lunceford, you went to LA. Why LA? What was going on there in the music scene?

Gerald Wilson: Well, you know, when I went to LA, actually the very first time with Jimmie Lunceford, we had just left Chicago. In the winter time, it's very bad; snow and ice and everything. So when I got to Los Angeles with The Jimmie Lunceford Band, I said, "Well, this is the place for me because I like the weather out here." So later on, I did. I moved to Los Angeles. And I've been living there for 60 years now. But I knew that Los Angeles would be big in television, which was not in, yet. There was no television at that time. And I said, "The movies are here. It's a good place to live to work in the movies and write music for movies and things like that. This is a good place to be." And that's what I did. And I was lucky, because I actually wrote for movies. I wrote for television. I was Redd Foxx's music director on the ABC variety show he had. And so it's turned out to be a nice thing for me living there. However, I consider New York as a home. I lived here. And I lived here when I was doing real good and I lived here when I was doing real bad.

Jo Reed: New York is a lot more fun when you're doing good.

Gerald Wilson: Yeah, but you find a way to exist in New York. I consider myself with seven homes in the United States. I lived here. I lived in Chicago. I lived in Memphis. I went three years of high school in Memphis, Tennessee.

Jo Reed: I was making notes when you talked about the cities you regarded as home. Memphis, Detroit, LA, Chicago, New York, of course Mississippi. We're talking about real jazz towns.

Gerald Wilson: Yes. Well, you know, Mississippi, of course, I was right in the middle of jazz, you know. I remember when the bands would come through from New Orleans. My home is 250 miles from New Orleans. It's a direct line, straight line, from New Orleans to Chicago. When King Oliver left, he left in 1918. And he went to Chicago. And he went there and he taught the musicians there. And I'm talking about black musicians, now. He taught them because the black musicians who had been born there, they didn't know how to really play jazz. Because there were no recordings. There was no radio in the early days. So they didn't have anything to listen to, unless you had been to New Orleans. So I got a chance to see many of those guys coming up with the bands, the traveling, going to Chicago.

Jo Reed: Detroit is also a big music town, a big jazz town.

Gerald Wilson: Absolutely. Absolutely. And that would be on account of, like, Jean Goldkette. I don't know if you know who Jean Goldkette is?

Jo Reed: No.

Gerald Wilson: Jean Goldkette was a white band leader. Jean Goldkette owned the Graystone Ballroom. Okay. Blacks couldn't go to the Graystone Ballroom. But every Monday night was Black Night at the Graystone Ballroom. And every Monday night it was a band like Duke Ellington, Jimmie Lunceford, Earl Hines, all of the big Black bands, Chick Webb and all of those people.

Jo Reed: And talk about a long time, you taught for over 40 years.

Gerald Wilson: Yes. I got into jazz in the college. You know, I taught jazz at UCLA for 20 years-- 22 years. I taught the history of jazz. Because I knew the history and that's why I did it. And the kids liked my class. I had 480 students in my class. And they made us cap it at that. Because the first year I did, I had over 500 students and there would be some sitting in the aisles. So the fire department said, "You can't have that many, Gerald, because we can't have them sitting in the aisles." So they stopped it for that and we capped it at 480. And it was full every year. And you had to pay to be in that class. So it was a big thing for the school. So I stayed there all that time.

Jo Reed: Gerald, what was it that you wanted to teach these students about jazz?

Gerald Wilson: Well, you know, I'm so much in love myself with jazz that I knew from the time I was about four or five years old, because of my brother, that I was going to be a jazz musician. Because my brother, he could play jazz on the piano and he could play some classic. And he would talk to me when he would come home from school. He graduated from Tuskegee. So he's really the guy that really pushed me on into it.

Jo Reed: And let me ask you, finally. You said that Duke Ellington is your favorite musician. Tell me why.

Gerald Wilson: First of all, let's tell you about Duke Ellington. Duke Ellington, as a pianist, he's one of the greatest pianists in the world of jazz. His style, they have never been able to copy him. The way he plays it and the way he brings in things, and he's a great composer as we all know. That's the thing about Duke Ellington. He's my favorite man. And I had met him. How did I meet him? While I was in school. A bunch of us kids that went to Cass Tech, whenever they'd come to play in Detroit at the Graystone Ballroom, we'd go up there and try to meet him. I went up and I said, "Mr. Ellington, I want to meet you. I love your music. And I'm so very happy to see you and hear you." And he was a nice man. He said, "Well, thank you, young man. Keep studying your music and doing things." I followed him in the Apollo Theater in New York City. And then, Duke called me in 1947 to orchestrate two of his compositions for him. And this would be a nice little story for you. I didn't hear from Duke Ellington again for nine years. Nine years. He called me up again at 6:00 in the morning. And said, "Gerald, I need some help." And I said, "Okay. Duke, what is it?" So he said, "I've got two numbers to orchestrate." I said, "Okay. What are they, Duke?" He said, "One is called 'Smile' that's written by Charlie Chaplin. The other one's called 'If I Give My Heart to You' It's another pop tune." So I said, "Duke, when do you need these numbers?" He said, "This afternoon, two o'clock, Capitol Records." So that morning he called, I just called my wife. She was visiting her mother in Glendale. I said, "Come on. We've got to get this record ready for Duke Ellington by two o'clock this afternoon." She came on over. She copied as I score each page, she's copying it. She's copying what I'm doing. And at two o'clock, we're there. And I said to myself, "They are two of the best orchestrations I ever made in my life."

Jo Reed: That was NEA Jazz Master Gerald Wilson. You've been listening to Art Works produced at the national Endowment for the Arts. Next week, author Julie Otsuka, whose novel

When the Emperor was Divine, is a current Big Read selection. To find out how art works in communities across the country, keep checking the

Art Works blog, or follow us @NEAARTS on Twitter. For the National Endowment for the Arts, I'm Josephine Reed. Thanks for listening.