Defining Creative Placemaking

In September 2012, NEA Design Director Jason Schupbach talked with Ann Markusen and Anne Gadwa Nicodemus, authors of Creative Placemaking, a white paper commissioned by the Mayors' Institute on City Design. Markusen is emerita professor and director of the Arts Economy Initiative at the Humphrey School of Public Affairs at the University of Minnesota where she also directs the Project on Regional and Industrial Economics. Her research specializes in artists, arts organizations, and cultural activity as regional economic and quality-of-life stimulants. Gadwa Nicodemus is the principal of Metris Arts Consulting, which focuses on research, analysis, and planning support on how arts and culture strengthen communities and vice versa, and writes and speaks widely on creative placemaking and artist spaces. Below is an edited version of their conversation about creative placemaking.

JASON SCHUPBACH: I want to start by paraphrasing your definition of creative placemaking [from the report Creative Placemaking] because this is the definition that we use here at the NEA. In creative placemaking, public, private, not-for-profit, and community sectors partner to strategically shape the physical and social character of a neighborhood, town, tribe, city, or region around arts and cultural activities. So that's what we're going to be talking about today.

Let's start with a general question about where you two feel like the field stands at the moment. What are the missing links? What are the things that you think have been accomplished?

ANN MARKUSEN: Well before we researched and wrote Creative Placemaking,NEA Chairman Rocco Landesman began traveling to cities large and small and asking arts and culture groups to come out of their doors and join him in meeting with mayors and other civic leaders, using his presence to give the arts and cultural sector considerable visibility. And the new Our Town and ArtPlace funding has electrified cities large and small, has seeded all kinds of initiatives. I have been traveling around giving talks and visiting our case-study communities and other creative placemaking efforts. Many leaders are saying, "Even if we don't get the funding, we're going forward." And I think that's very exciting.

ANNE GADWA NICODEMUS: Yeah, it's really exciting to see so much interest and momentum. The state public art funding in Connecticut has adopted a creative placemaking focus. Kresge Foundation and William Penn Foundation and the Educational Foundation of America are all focusing on creative placemaking. It's also great to see an interest in other federal agencies in how arts and culture can invent placemaking. What I think is a missing link is that people are still really trying to understand how to actually go about this. They're interested in the idea, but they're not sure necessarily what it means or how to start or how to actually pull off the projects that they aspire to do.

|

SCHUPBACH: If someone's going to pursue this type of project in their community, what are the steps that they might need to take? Where are the places where you feel that we don't have as much understanding at the moment?

MARKUSEN: One thing that's baffling for many people is that they're really not sure what the outcomes are supposed to be or what partners and funders expect. For instance, some are wondering whether they're supposed to be about creating jobs or increasing property values or home ownership, or whether they are expected to attract tourists rather than focus on service to existing residents. In our study, we placed arts and culture at the core of creative placemaking, but arts and cultural outcomes are often underplayed in the rhetoric about expectations. Creative placemaking is about getting artists and designers, community culture groups, arts research groups, cultural affairs offices, and arts organizations out of their silos and into the neighborhoods and regions around them. Our study demonstrates how people in communities are mobilizing arts and culture to make the quality of life better where they live and to raise the visibility of arts and culture so that many more people are participating.

GADWA NICODEMUS: There's a lot of unchartered territory about what exactly the outcomes should be and how to then reach that. In our definition, creative placemaking animates public and private spaces, rejuvenates structures and streetscapes, improves local business viability and public safety, and brings diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired. But ours is not the only definition out there. The NEA is still using it prominently, but when the NEA talks about outcomes in its funding requirements, it emphasizes livability. ArtPlace is certainly another major funder and policy shaper, and their definition emphasizes vibrancy and diversity. Even within the outcomes that we described in our definition, there's a range. I don't think that, necessarily, a creative placemaking project would have to try to hit every one, but, to me, the spirit of it is more than just one of the impacts. I appreciate Ann's call for more emphasis on keeping arts and culture at its core, and focusing us on one of the intrinsic arts impact that we do highlight: bringing diverse people together to celebrate, inspire, and be inspired.

SCHUPBACH: I do feel like a lot of that has to be locally driven and that communities should define what the expected outcomes are. We're really interested in artistic practice that's happening at the local level, and what outcomes that communities think they might be able to achieve through that practice. I think it's very much dependent on the actual project type that they're working on -- building artists workspace will have very different outcomes in a community versus temporary public art festivals. So we're trying to build a flexible enough system so that people can build their own outcomes, and do the project types they want to do. With that said, I do want to frame the next part of our conversation around the question that we get a lot here. Does this work everywhere? How is it different or the same in places that are maybe more rural, or urban, or suburban?

GADWA NICODEMUS: I think this is one of those areas that really needs more investigation. My next major project is trying to really dig deeper into the differences between types of places and types of projects, and trying to get us those lessons learned and initial impacts. One thing that I will say is that in smaller communities it may be easier to try to get some of these projects off the ground. We really emphasize partnerships, and in smaller communities you just have fewer players, but they also have an additional challenge [of maybe having] to reach outside of their immediate area to increase support. For instance, in Arnaudville, Louisiana, they reached out to their parish tourism offices and the French Consulate in New Orleans and tried to build bridges to get support and resources to do their project that just weren't coming from their immediate town.

MARKUSEN: One of the mistaken beliefs among many arts advocates is that you have to look outside of your community for participation, funding, and support. Yet in most of our case studies, initiators started by imagining that they would be serving local audiences. So even in Arnaudville, yes, they sought support and funding outside, but mainly they created a space, NuNu's Café, to host live music and visual arts and act as a gathering place. Only after local people got engaged and excited about it were they able to build their reputation and attract funding and people from farther afield.

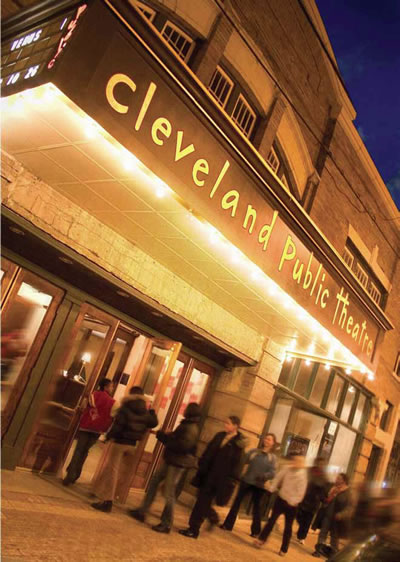

Most good creative placemaking grounds itself on distinctive features and capabilities of the community, and service for the community. To form Cleveland's Gordon Square Arts District, three theater organizations joined forces with an established community development corporation to restore two old theaters, build a new one, and link them with a streetscape to create a vibrant arts and cultural area on the west side of Cleveland, far from the city's flagship arts institutions. In San Jose, California, the ZERO1 biennial festival marries art with technology, engaging local artists and arts organizations to share their work and spaces in an event targeted at international as well as local participants. By design, it intends to help the people of Silicon Valley see themselves in a different way -- not as just a techie, geeky place, but a place where rich, ethnically diverse, artistic traditions have much to offer.

|

SCHUPBACH: I want to jump in now a little more specifically to some of the different kinds of project types that we fund here at the NEA. Let's start by talking about how you really set the stage for creative placemaking to take place if you are a policy planner at the city or local arts agency. I'm sure that both of you get phone calls all the time that say, "How do I start doing this? And how do I know that the arts are the right solution for our neighborhood? If this is our community development project, how do we do the arts piece of it?"

GADWA NICODEMUS: I would encourage people to just take a step back: all creative placemaking projects start with an idea. So there's a creative initiator -- sometimes that's an artist. Sometimes that's somebody from the public sector. It could be from the private sector. You can look at different examples of past projects, but what strategies might this be employing? Where would it take place? What are the desired outcomes? And so just kind of brainstorming, and then they have to consider, does this advance your organization's mission or is it employing your particular passion or skills? And you have to answer that for yourself. I think it's great to encourage arts organizations to get out of their silos, but if it's not your core expertise or if it's mission creep, then maybe it's not the right fit for you.

So then the next step that I would encourage is to think really strategically about coalition building. So who are the partners that might really champion this -- not just to write a letter of endorsement for your grant application -- and how would your idea advance their core interest and missions or those of their constituents? And if it doesn't, you need to go back to the drawing board, and either identify different partners or adjust your idea. It's a nice, iterative process that you can do in close collaboration with these partners to try to get something that really speaks to the needs and assets of your community, and then advance the work. It's a challenge to maintain that political will as the project is evolving -- to make sure that it's still rooted in what the original idea was and meeting the needs and the interests of your partners.

SCHUPBACH: What are the times you've said, "This is not going to work for you?" When was a time when you came into a community and said, "The art strategy is not the right strategy for this particular place," and why?

MARKUSEN: In some cases, people have wildly unreasonable visions for creative placemaking. It might involve a target place or community far from where they live, or an art form or cultural practice that the initiators know little about. Or, some initiators, heeding the NEA's encouragement of partnerships, approach a wide swath of potential partners, which would make planning and implementation unwieldy. These are examples of cases where I would urge caution and redesign.

In so many of these efforts, people spend lots of time doing just what Anne's laid out -- trying to find the political will and find partners -- and spread themselves too thin. The four central partners in the Gordon Square initiative reported spending at least a third of their organization's time for several years on the Gordon Square Arts District effort, time taken from their own programming. I don't think that's unusual. That's how time-intensive creative placemaking can be. So initiators have to choose partners who are skilled, committed, and complement their expertise.

SCHUPBACH: I think what's been very exciting about this work for the last two years is that it has started a lot of new conversations between people who have been doing community development work (in the typical structures of support for community development) and the arts world. We've been successful in getting people out of their silos, I think, very much so, but some of the feedback I've been getting is that artists are not properly trained in art schools necessarily to participate in those conversations in a way where they can be as effective as possible. Hence, one thing the field needs to work on is helping artists and other creative organizations understand how to participate in these conversations. How do you get artists involved in the planning process? What are the right first steps that communities should take as they're beginning these conversations?

GADWA NICODEMUS: From what I've seen, it does take a lot of discussion and thought. The initiators and partners really have to ask themselves in conversation with artist leaders, what is the unique value that they could bring to the project? If you don't specify that, then everyone's sort of going to be unhappy. The other thing that I see a lot is a naïveté or a lack of appreciation surrounding compensation for artists' time and creative contributions. The equation for artists to participate is different than for other workers. There might be a salaried director of local cultural development agencies that can afford to go to meeting after meeting because he's on the clock for his job, but an artist, if they're self-employed, that's taking away time that they have for project development or other freelance work. So I do think that if you want artists to be involved in whatever way it is, you need to actually have a budget for their time and materials. And that's something that I haven't always seen carried through or able to be sustained if costs get cut.

MARKUSEN: One of the things I think is so brilliant about the way that the NEA has structured your Our Town grants is this idea about having a partnership between a public sector agency and a not-for-profit organization and one of them has to be an arts agency. And I think that that's a really important framework, because even though we really were stunned to see how important artists were as initial leaders in these projects, in many cases they didn't end up leading it. I can think of two cases in our study where artists were formally involved in an ongoing way. The Phoenix effort to infuse art into their public infrastructure around canals and freeways is one. And the other is the Philadelphia Mural Arts Project. A mayor with anti-graffiti ambitions partnered with artist Jane Golden to set up an enduring project that serves multiple placemaking goals and has buy-in from several city agencies. Artists are going to get involved in creative placemaking out of love and desire to serve, not as a career step or for pay.

Artists willing to work with city and other bureaucracies are exceptional. They have to know what they don't know. Visual artist Marcus Young serves as an ongoing artist-in-residence with the City of Saint Paul, Minnesota. When he first took on this position, he sat with engineers in the public works department. He sat through a lot of meetings, he listened, and then he would approach people with ideas that came from his expertise. If you want artists to be involved in the planning process, you must respect that they're artists, and they do have to make an income, and you must look for the exceptional artist.

|

SCHUPBACH: So let's jump into artistic practice itself, and the question we get a lot at the NEA: how do I know when a project is a livability project versus just the sort of business as usual, artistic practices that people are doing? When is a festival just a festival, and when is a festival truly a strong livability project?

MARKUSEN: There should be a permanent outcome, and it doesn't necessarily mean a new building or structure. It can be a venue that's animated and run by an arts organization or a community group. It can be a series of ongoing artistic performances, preferably participatory, like the LA Music Center's Friday night dances in the plaza.

I think festivals are particularly tricky. As an economist, I think, well you have this huge expansion in population for two weeks, and then everybody goes home. It's not providing that much permanent income for artists or arts organizations or employment for others. But ZERO1's vision for its biennial has from the beginning been about jump-starting new enterprises in the valley that merge arts and technology. They believe there is an increasing amount of visual and oral content in what Silicon Valley makes, but the valley still thinks of itself as all about digital X, Y, and Z and as crowded with engineers. They want to change that. They've been able to attract corporate sponsorship because they anticipate that there will be new businesses coming out of the event. ZERO1 also showcases the existing minority arts and cultural communities of Latinos, Asian Americans, and African Americans, using their venues and neighborhoods as biennial staging areas.

Let's return to some other models. Arnaudville, Louisiana. At the beginning, their creative placemaking began with a café for music and visual art. But soon, initiator George Marks and others realized that they were surrounded by French language-speaking people, including Cajuns (originally Acadia via Canada) and African-American Creoles, originally from the West Indies. They decided to set up language tables where people can gather monthly to speak French. They made sure that everybody was welcome no matter how they pronounced French. They've really developed a far-reaching reputation. People are coming to their summer language-immersion camps. The French Consulate in New Orleans has linked them up with Brittany, in France, and has given them some financial support. They are turning a shuttered, small ‘60s hospital into a French-language immersion school.

I want to underscore how long a good creative placemaking effort takes. It took the Gordon Square initiators five, six, seven years before they got the streetscape designed, funded, and completed. And another several years to raise the funds to renovate two of the theaters, now up and running, and they're still building their third.

GADWA NICODEMUS: To Jason's question on how do you know when a project is creative placemaking versus business as usual, what I try to come back to is the original definition. Does it involve strategic action by cross-sector partners? Is it place-based? Is it rooted in arts and cultural activities? Does it have one or more of the outcomes that we outlined? The gray area is not just for festivals -- there are some really interesting projects that are more ephemeral in nature, like tactical urbanism and temporary pop-up art spaces. I'd have to look at more detail about the particular project to see, was it a one-off by an artist or was there more involved strategic prospect and partnership to get this idea, or did it lead to that?

|

SCHUPBACH: To wrap up, I'd like to talk to you about the thing that you both wanted to talk about when we first started, and the thing that's on the tip of everyone's tongue, and that's evaluations of projects and evaluating success in the outcomes that people say that they want. Both of you are evaluators, and I think something that'd be useful for folks is to put some perspective on the kind of work that needs to be done to effectively evaluate a project. How much time does it take a researcher to really do that? What kinds of interviews and data do you guys use when you go in and do individual evaluation project? What does it cost?

MARKUSEN: I'm taken aback at the sudden emphasis on performance and especially the resort to project-unrelated indicators as evaluation. As someone who spent two decades studying high tech and the occupations of engineer and scientist, I did not observe the same pressures to produce in those innovative fields. If you get a grant from the National Science Foundation, all you have to do is show that you've published your work, because they understand that it's research, it's exploratory. They are happy if you learn from failure. It's how you advance the project that bears on whether you get funding next time.

Most high-tech creative initiatives are funded by venture capital. If you have an idea, a new invention, and it's at the point where you want to take it into development, you can often find venture capitalists to invest in it. And they're going to give you five to seven years of their time. They're going to counsel you because you're an inventor, and they know that you don't necessarily know much about management or marketing. That kind of model is ideal for creative placemaking. To build a partnership, to get your initial funding, to do the design work, to build structures and organizations, put together the festivals -- those are 5- to 15-year projects that are truly creative, and there's going to be a lot of readjusting and learning along the way.

SCHUPBACH: I agree with you completely that funding needs to patient. My question is, so you are 15 years out -- what does it take to evaluate success on those projects where they are far enough along that you feel like there can be an evaluation done?

MARKUSEN: Evaluation has to be based on the initial conditions that were part of the contract, so it has to start with what the initiators say they wanted to achieve. So look, for instance, at our case study in Portland, involving light rail transit stations where they wanted to ensure ridership and proposed to engage artists to work with communities so that each station's design and artworks express what the community wants them to say about themselves. At the end of 15 years, they can say, yes, they have achieved more than their ridership [goals], and station design was an important contributing factor.

GADWA NICODEMUS: First, there's the question: What is it that you're evaluating? How do wrap your hands around it? What is it that you're evaluating, and then how do you define success? Where you draw the line is something I struggle with as a researcher. People also need to make sure that they are considering appropriate geographic scale and time scale that has to be matched to the project.

If you're trying to understand how a particular intervention benefitted multiple users and impacted a place, then I think it's important to, what I call, "triangulate" between quantitative secondary data -- that's census or the county business zip code data -- as well as qualitative sources. So talk to a lot of interviewees, a range of them, including the known critics. By using those different elements, we can try to understand what change happened and piece together what the intervention's role was and other contributing factors. There certainly is a danger around conflating causality and correlation, but we can still learn a lot by just understanding what the change was and trying to tell the story of the different factors. This type of evaluation is challenging and time- and resource-intensive. However, the initiators of a project can also define their own performance metrics, so that there are self-evaluation elements that they can be doing on an ongoing basis to try to improve their strategy and communicate results to their different stakeholders.

SCHUPBACH: The NEA allows people to define what their own success measures might be within the context of livability. I think we feel like the purpose of our indicators project is to clarify for the country and for arts organizations and the other people that we fund just what those datasets are that might be related to the project that they're funding.

I do think you can end up in a place where some people would say, "Well, it didn't show change. The data didn't show any change," when what really you need to continue to do is that deeper evaluation and do qualitative research at the local level, which is expensive. So it is a conundrum for funders -- there's limited money and these kinds of project take a long time to show "success," and we need to prove success to our authorizers in the short term.

Last question -- where should the next phase of research in the creative placemaking field be?

GADWA NICODEMUS: First, I think more peer-to-peer learning is one pressing opportunity. It might be convenings where people are presenting on their project about what worked and what didn't. It might be webinars. I know that the NEA sponsored a series of broadcast webinars from the [Our Town] panel. I thought that was a great start.

I'm also hearing that people want more in-depth case studies -- pairing those in-depth resources with the people that want to know practical skills of how to go about this. There are so many interesting efforts that we could learn from. I can't even keep up with all of the wonderful projects that the NEA and ArtPlace are funding. Personally, I'd really like to learn the details behind Theaster Gates' work. He's based in Chicago, but works in a few different cities. He's a really world-renowned artist and very smart about how he uses his art practice to engage different communities, especially African-American communities, and bring assets back into those. Then, just right next door to my new hometown in Easton, Pennsylvania, is the ArtsQuest Center in Bethlehem; and that's such an iconic story of how a community struggled with industrial decline. This huge steel plant, Bethlehem Steel, closed, and it was partially adapted into a massive arts center.

I'd love to see more of a longitudinal approach to research be supported; to track a few projects that either exemplify a particular place or a particular strategy and look at them over the long term. I think that might give us richer insights than the indicator efforts, or maybe they can be done in tandem. For the field to move forward, we have to keep sharing information about who else is out there -- how they're approaching these projects and what we can start to see about impacts and outcomes.

MARKUSEN: I second everything Anne said. As somebody who's worked in urban and regional planning for 35 years, it's sad how many people reinvent the wheel all the time. We need lots of case studies, a daunting project, because there are things going on all around the United States, many unique but with important lessons. And we have to have studies of failure as well. How can we foster learning from others? One way would be to have a website where people are invited to write short things -- 900 words max -- about their creative placemaking experience, success or failure. And have somebody organize it by topics for easy access. We need a lot more cross-fertilization.