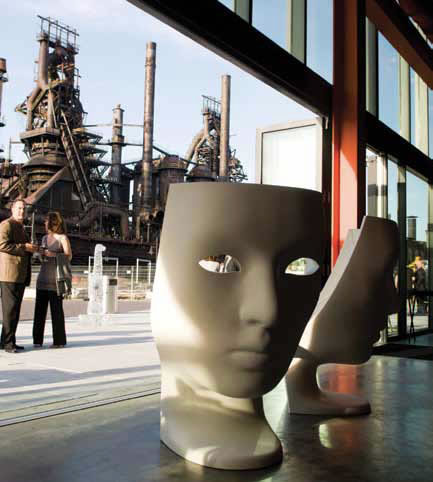

Smokestack Lightning

The SteelStacks campus with the Levitt Pavilion in the foreground in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Photo by Mark Demko

When Bethlehem Steel shut operations in 1995, the plant that had once been Bethlehem, Pennsylvania's main architect of economy and identity suddenly became its greatest scourge. The city was left with a 1,800-acre brownfield, the remnants of an industrial dream gone sour. "It was a constant reminder of what we used to be," said Julie Benjamin, president of ArtsQuest, a not-for-profit that uses the arts as an economic engine. The most inescapable reminders were the five 20-story blast furnaces that loomed over Bethlehem like a desolate version of the skylines they had once helped build.

"You literally had this old Bethlehem steel mill right there lurking above you," said NEA Chairman Rocco Landesman, who visited the site in 2010. "So what do you do with it? Do you take it down? Do you ignore it and make the best of it? Or do you actually try and engage it as part of the history of that place, part of its culture, and try to make it into a positive?"

Today, the furnaces form the awe-inspiring backdrop of SteelStacks, a 9.5-acre arts and cultural campus located on the Bethlehem Steel site. Developed by ArtsQuest in partnership with the Bethlehem Redevelopment Authority, SteelStacks has welcomed one million visitors since opening in May 2011. The campus is home to year-round programming, a first-run independent movie theater, the stunning Levitt Pavilion, a visual arts gallery, and numerous outdoor spaces for festivals, concerts, and craft and farmer's markets. Although the Lehigh Valley has long been home to prestigious art institutions such as the Allentown Symphony, SteelStacks was designed to showcase contemporary art forms that weren't readily available in the area.

Mayor John Callahan, who is a Bethlehem native, credited the Mayors' Institute on City Design (MICD) with providing guidance during the early stages of the site's redevelopment. MICD is an initiative of the NEA in partnership with the American Architectural Foundation and the United States Conference of Mayors. Since 1986, the Mayors' Institute has helped transform communities through design by preparing mayors to be the chief urban designers of their cities. In February 2004, a month after taking office, Callahan presented Bethlehem's design challenge at an MICD conference in Charleston, South Carolina. Among the most memorable -- and prescient -- feedback he received was to leave the blast furnaces as they were. Once a symbol of the city's industrial strength, the furnaces now signify Bethlehem's transformation into a regional arts capital.

|

"It's one thing to feel that sentimental connection if you live in the community," said Callahan. "But to have national and international experts see how important they are, it really makes you say, ‘Hey, we're going to stick to our guns and make sure that these things don't go anywhere.'" Of the $2.2 billion worth of development projects that have taken place during Callahan's tenure, he says "every one" has benefitted from what he learned at the Mayors' Institute.

In 2010, Bethlehem intersected with MICD once again when ArtsQuest received a $200,000 MICD25 grant from the NEA. These grants, designed in honor of MICD's 25th anniversary, were the precursor to the agency's current Our Town program. They signaled a renewed focus by the Arts Endowment to bring art into everyday community spaces, and into the daily lives of every citizen, even those "who never would think of buying a ticket to a ballet, opera, a play, a museum," said Chairman Landesman, who announced the MICD25 grant recipients at SteelStacks. ArtsQuest used its MICD25 funding to commission and build The Bridge, the signature sculpture of the SteelStacks campus. Featuring a natural gas flame snaking along a curved piece of steel, The Bridge -- much like the rest of SteelStacks -- is at once an historical reference and a stunning piece of contemporary art. Benjamin said the sculpture has become a part of the campus's daily ritual as people wait for it to ignite come evening.

In the case of Bethlehem, the aesthetic benefits of adaptive reuse are hard to ignore, but the city's current economic profile has become just as eye-catching. In May 2012, the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia published a report called In Philadelphia's Shadow: Small Cities in the Third Federal Reserve. Among the 13 cities studied in the report, Bethlehem was reported to earn the highest median household income, and boasted the lowest poverty rate, the lowest violent crime rate, and the second lowest unemployment rate. "There weren't many people a decade ago imagining that with the demise of Bethlehem Steel that we'd be on those kinds of lists," said Callahan.

|

Benjamin believes that at least part of the reason that Bethlehem is where it is today has to do with the city's emphasis on arts and culture -- a belief echoed inIn Philadelphia's Shadow. In 1984, ArtsQuest launched the annual ten-day MusikFest, which was designed to "provide that economic shot in the arm." In 1996, it converted a former banana distribution center into the Banana Factory, which offers art classes and affordable studio space. And of course, there is SteelStacks, which Benjamin estimates has generated $29 million since opening.

Both the Banana Factory and SteelStacks are located in the city's South Side, which has become fertile ground for galleries, theaters, and boutiques. Tony Hanna, executive director of the Bethlehem Redevelopment Authority, cited the Banana Factory in particular as "a seminal project for the city." "It took us to the next level, one where we weren't just engaged in showing art," he said. "It was a place where artists could come and do their thing, do their work, and create art."

"Things began to grow from there," he continued. "A whole community grew up around it in terms of our second downtown," which Hanna described as an artsier, funkier version of Bethlehem's historic district.

With the addition of SteelStacks, Benjamin said that the South Side has grown not only as a community destination, but as a means of recruiting and retaining skilled employees for Bethlehem-based companies such as Air Products and Synchronoss. "[SteelStacks] is something that neighboring communities don't have that we do have to offer: programming that's year-round, programming for children and families, ten different music festivals," said Benjamin. "It allows [companies] to say, ‘Here's what we have for you when you relocate to the Lehigh Valley.'"

And there is still more to come. Forty-six units of affordable artist housing are planned for the former St. Stanislaus Church and a second site at East Fifth and Atlantic Streets. In August, a study was launched to determine the feasibility of turning the Hoover-Mason Trestle, which connects SteelStacks with the nearby Sands Resort & Casino, into an elevated walkway similar to the High Line in Manhattan.

As Callahan reflected on all the changes that have transpired since he was elected, and all those in the works, he noted how incredible it has been to oversee the transformation of his own hometown. "I always had this dream, when I first made the decision to run for mayor, that there was going to be a time in my life when I could load up the grandkids into the car and drive around Bethlehem 30, 40 years later and point to a few things that happened while I was mayor," he said. His grandchildren should plan for a long car ride; there might be a lot to point out.